World Photography Day: Xavi Bou’s photos show the magical traces birds leave in the sky

10 years since starting his celebrated ‘Ornithographies’, Xavi Bou discusses the impact of climate change on bird migrations.

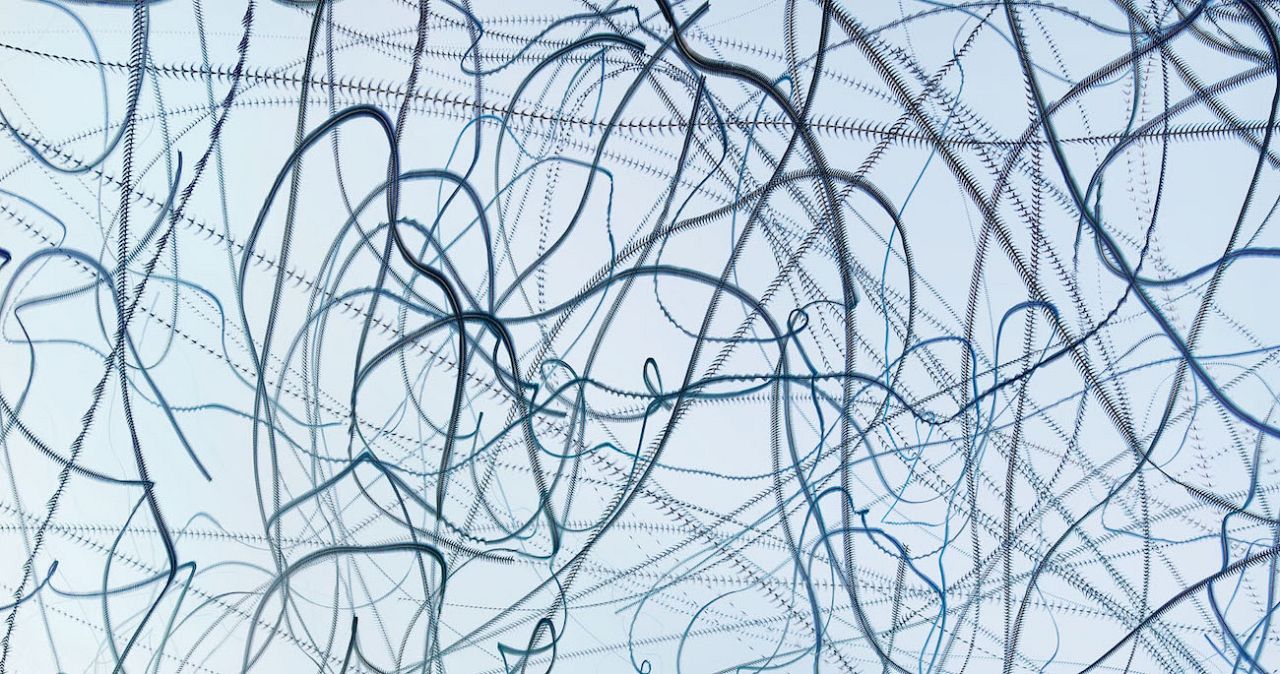

During lockdown, in a flat on the Costa Brava, Xavi Bou became even more obsessed with birds. The Spanish photographer had already made a name for himself with his extraordinary pictures, stringing together hundreds of snapshots of birds into collages of movement.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

His mesmerising images capture roughly 20 seconds, overlaid to show the idiosyncratic flight paths of playful robins, dancing starlings and stiff-winged fulmars.

“All my life I’ve been interested in nature, especially in birds, but it was not at that level of madness,” he tells Euronews Green.

Confined to a balcony in March 2020, which coincided with bird migration, he counted 50 species. He began drawing them with his children, and learning their calls - a practice he recommends for anyone who wants to “feel you have superpowers.”

Bou wasn’t alone in paying closer attention to the natural world. “It was magical that many people got interested in birds and nature during the lockdown and have since followed this passion,” he says. “It was a great moment for conservationists.”

Those who discovered Bou’s ‘Ornithographies’ in the pandemic no doubt felt something of the same vicarious freedom.

“One of the most wonderful things is the different people who have got in touch with me because they were inspired by my work,” he says. They include dance choreographers, orchestral composers, bridge architects, sculptors, tattoo artists, biologists, physicists and scientists - notably those involved in biomimicry, which applies nature’s solutions to technology.

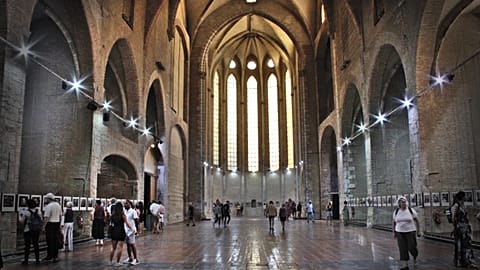

This diverse fanbase speaks to the way ‘Ornithographies’ hovers between art and documentary. Bou, 43, is clear that the decade-long project comes down on the former side, however; “for me the difference of art is that the story is open.” His exhibitions give little technical or geographical information, leaving viewers free to travel in any direction.

Bou’s favourite photo depicts the flight paths of starlings through a tree. It feels poetic and ecological in the way it draws out the links between birds and branches. “Most of the time you see birds in a tree but in a specific way, and then suddenly looking in this way it’s like it's connected, it’s the same, like the leaves of the tree.”

The first picture was unplanned, and it sent him seeking out similar scenes. It’s not easy, though - many things have to happen to capture such a starling dance. The iridescent birds only flock in winter, around October and February in the Mediterranean. After feeding in fields in smaller groups during the day, they look for a safe area to spend the night - such as wetlands, or cities like Rome.

Bou’s photos capture the moment the ‘murmuration’ comes together, he explains, joining in trees around an hour before sunset. Even more precisely, some of his series rely on the appearance of a hawk at this point - sending the flock into a convoluted dance to confuse the hunter.

“One of the beauties of working with nature is that your agenda is linked to the natural agenda,” Bou says. So he’s well attuned to the disruptions unfolding today.

A tragic example is the experience of swifts in Spain. The birds arrive in April and have chicks around June to July, nesting in the nooks and crannies of houses. But the recent heatwave made the temperature inside the nests unbearable, causing some chicks to jump early to their deaths.

The photographer fears that swifts - one of his favourite birds to shoot because they spend so much time in the sky - could disappear from southern Europe altogether as temperatures rise.

It’s a similar picture elsewhere - in the “magical” lake of Gallocanta where hundreds of thousands of cranes usually winter, cutting a V shape through the cold air. And in Villafáfila, where fewer and fewer geese are making their way from the Netherlands.

From the very beginning, Bou’s experience of nature was wrapped up with humans’ impact. He grew up in Prat de Llobregat, an industrial town which straddles Barcelona’s airport and the Delta de Llobregat, one of Catalonia’s most important wetland areas.

Walking around these with his grandfather, the young Xavi would encounter many kinds of birds but also flagrant pollution - rivers stained blue or red depending on what colour of ink the industry was using that day.

Much has improved since the 1980s, but the airport’s expansion has put more pressure on the birds - a mixed progress Bou sees around Europe. “One of the worst things for nature is the loss of habitat,” he says.

The idea for ‘Ornithographies’ came while out on a walk in 2012. Observing pawprints in the ground, he wondered to himself ‘what kind of tracks are birds leaving in the sky?’, imagining the invisible trails almost like an aeroplane.

Despite the runaway success of the project - which has taken him from Spain to Iceland, Yellowstone National Park in the States to the Outer Hebrides - Bou still makes sure to spend time in nature without his camera. “The mentalities are different because one is to be mindful and enjoy all the senses, and the other is more focused.”

There’s a restlessness to his explorations, a refusal to find any of nature’s realms off limits. On holiday at present, he enthuses about taking photos underwater. And he’s embarking on a new project to capture the insect world, which is undergoing “a massive extinction in front of our eyes.”

Birds are an endless source of fascination, however, and ‘Ornithographies’ will surely be a lifelong project. The 43-year-old recently discovered the role of the ‘augur’ in Greek and Roman culture - a person who read the movement of birds and other ‘omens’ to know the future. “When I read that it blew my mind,” he says, “because, wow, they would definitely love my work.”

In Italian and Euskara (the Basque language), birthday and Christmas greetings have their root in ‘augury'; people are essentially wishing each other ‘good birds.’ “The humans of the past were more related to nature than us for sure,” says Bou.

Whether his photos are read as records of loss, beauty or just genius camera work, his goal is simple: “I want to encourage people to stop and look at the sky.”