Japan gave €7.6 bn more than its fair share of historical emissions.

Climate finance will make or break COP27 and there’s no doubt who most countries feel should be picking up the lion’s share of the bill.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The US is falling $32 billion (€30.7 bn) short of paying its ‘fair share’ of the $100 billion that developed countries promised developing nations by 2020, new analysis shows.

Given that the US is responsible for more than half of the historical emissions unleashed by richer countries, it should have given $39.9 billion (€38 bn), according to data from Carbon Brief.

A far cry from the $7.6 billion (€7.3 bn) it stumped up in 2020.

At the other end of the spectrum is Japan. The East Asian country gave $7.9 billion (€7.6 bn) more than its fair share of historical emissions. By this metric - followed by France and Germany - it’s well ahead of the pack when it comes to industrialised nations.

So is Japan doing so well on climate finance?

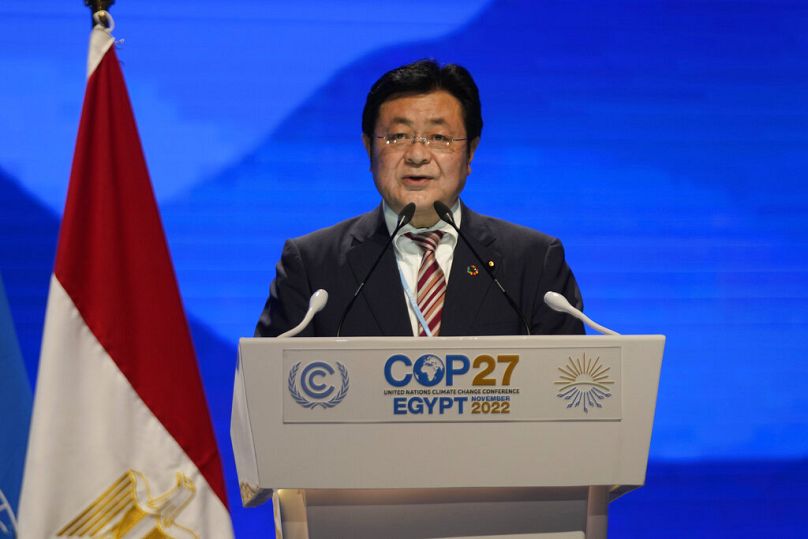

Speaking to Euronews Green, Japan’s senior negotiator for climate change Sugio Toru attributes part of his country’s success to stability in leadership - as far as climate attitudes are concerned at least.

While Biden had to bring the US back into the Paris Agreement last year after Trump took a huge backwards step out, Japan has been trying to “fulfil our maximum commitment possible,” he says.

The government hasn’t had its eye on meeting an equitable amount of finance exactly, partly because that comparative data was only recently released.

But there’s a common thread pulling Japan, France and Germany to the top of the leaderboard when it comes to paying proportionally more than their responsibility for historical warming.

All three gave much of their finance in the form of loans rather than grants: 86 per cent, 75 per cent, and 45 per cent respectively.

Loans come in different shapes and sizes, says Japan

More climate finance in the form of grants rather than loans is one of the repeated requests of developing countries. It’s only got more pressing during COP27.

“Countries across the Global South are already facing impossible debt burdens as a result of the pandemic and the global cost of living crisis. Providing climate finance in the form of loans would be tightening the shackles of this debt trap at the worst possible time,” says Nick Dearden, director of Global Justice Now.

“Industrialised countries have caused the climate crisis, they should not be asking to be paid back for the costs of dealing with it in the Global South. All climate finance should be grants with no strings attached.”

But Toru defends Japan’s record on this front, pointing out that the ‘Yen loans’ it offers are long term concessions offered on a favourable basis, with interest rates set at 0.1 or 0.2 per cent. Countries don’t have to start repaying them until 20 to30 years later, he says, with a much longer grace period than they would receive from commercial lenders.

“It’s like comparing an apple with a strawberry,” he says of the different kinds of grants and loans being given.

Where is Japan’s climate finance going?

The roughly 14 per cent of finance that Japan does deliver in grants is intended for climate vulnerable countries like hurricane-hit islands in the Caribbean, adds Toru.

“When we have a joint infrastructure project, for example, to construct a metro line in India or Egypt, we give loans,” he explains, because this can ultimately be paid for by users. This kind of project would come under mitigation finance because it’s helping the country to cut CO2 emissions.

But developing countries also desperately, and increasingly, need more money for adaptation - which has long lagged behind, as the latest UNEP emissions gap report shows.

Last year Japan agreed to double its adaptation finance, to reach around $14.8 billion (€14.2 bn) in total by 2025.

Where does Japan stand on loss and damage?

Loss and damage is the third category of finance dedicated to compensating countries for climate disasters. It’s the litmus test of this COP’s success for developing countries.

The issue made it onto the agenda for the first time at COP27. And though campaigners’ hopes are dwindling as the summit runs into its second week, some delegations’ expectations remain “very high”, according to one senior negotiator.

“I understand the frustration of developing countries,” says Toru. “We have so many typhoons coming to Japan a year,” he explains, making the country well-placed geographically to empathise.

This is also something of a sticking point, however.

“Developing countries can’t claim to be the only ones suffering from climate change,” he adds.

Given Japan’s relative wealth, it’s hardly surprising the delegation appears to be taking a more measured approach to setting up a new finance facility.

“First we need to understand where the gap lies,” says Toru, a Foreign Affairs minister back home. Japan is already providing significant amounts of humanitarian aid, he claims and sharing its expertise through the Sendai Framework for Disaster Reduction, launched in 2015.

“A human life would be saved with this kind of [aid] system, in the event of a natural disaster… but buildings, power plants and so on, that’s where the gap is.”

Is the Global Shield a solution?

To fill this gap, Japan is aligning itself with the ‘Global Shield’ - a disaster risk insurance scheme first proposed by Germany and now adopted by the G7 and V20 (the block of countries most threatened by climate change).

It’s met with mixed reactions. While civil society groups welcomed the Global Shield as a sign that richer countries recognise their need to act, they’ve also warned that it cannot distract from the primary need for a new loss and damage fund.

“Disproportionate focus on a new mechanism that does not cover slow onset events such as rising sea levels or loss of language and culture cannot meet the needs of communities on the ground,” comments Harjeet Singh, head of global political strategy at Climate Action Network (CAN) International.

Where does the current stalemate on loss and damage leave countries?

Japan’s history also makes it receptive to the calls of developing countries on climate finance, suggests Toru.

In 1961, the country got a loan from the World Bank to help build its famous Bullet Train line between Tokyo and Osaka as it recovered from World War II.

“We know how difficult it is to rebuild a country,” he says. And despite having closer ties in Asia, the minister says Japan is keen to extend its finance wherever it’s needed most, including in Africa and the Caribbean.

But with the third highest GDP in the world after the US and China, Japan is far better able to protect itself from escalating climate change - and this shows in its attitude towards the loss and damage negotiations.

Turo says that Japan and other developed nations want to discuss the details now and figure out the need for a new facility later, while those in the Global South want the facility founded first.

“If we don’t find an appropriate measure [within existing climate finance structure] then we need to find a new one. It’s a step by step approach,” says Turo.

“COP’s an annual process so we’d have to put it back - but it’s not healthy,” he acknowledged.

This restrained stance aligns with that of New Zealand. “Establishing a fund without certainty around what that means would require high levels of confidence that we have a shared understanding of what we are working on, and how,” the country said in a statement on Saturday night.

“Listening to the interventions, it doesn’t seem like we have this.”

New Zealand has previously said a loss and damage fund is urgent and added that it committed funding last week.

“But we also think we need to get this right.”

Taking the time to get it exactly right might seem like something of a luxury from the submerged shore of Tuvalu. The moveable timeline on loss and damage funding is yet another way in which countries are divided by the demands of climate justice.

New Zealand won CAN’s ‘fossil of the day’ award yesterday for its “regressive intervention on the loss and damage agenda”.

Japan was the first recipient for being ‘the world’s largest public financier for oil, gas, and coal projects’. The network claims it contributed $10.6 billion (€10.2 bn) per year on average between 2019 and 2021.

“No country’s finance is flowing more than Japan’s - but in the completely wrong direction,” says CAN.