Money given to help developing countries adapt to climate change must not create new injustices, says Professor Molly Scott Cato.

Climate finance is one of those terms we’re hearing a lot at the moment as the UN climate conference, COP26, dominates the headlines. But what does it actually mean and where does all that money go?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Like a lot of the topics on the table at COP, the term sounds confusing when dressed up in jargon - but it’s crucial to understand as it cuts right to the heart of climate justice.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) defines climate finance as “local, national or transnational financing - drawn from public, private and alternative sources of financing - that seeks to support mitigation and adaptation actions that will address climate change.”

As you can see, that means finance can flow from a number of different directions. In fact, there’s no universal definition for what counts as climate finance, as heads of state chose to keep the finer details loose to reach an agreement.

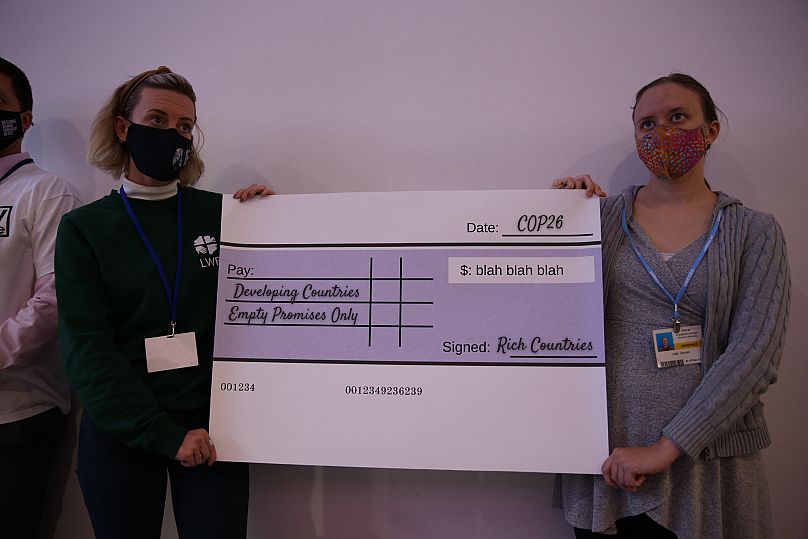

At COP15 in Copenhagen, wealthy countries agreed to “mobilise” $100 billion (€86.4 billion) every year in climate finance by 2020 - a target they have admitted won’t be met until 2023. It’s both too late and too little according to developing countries, and some are now demanding at least $1.3 trillion (€1.1 trillion) a year for the rest of the decade.

Such large sums are desperately needed to both support these countries’ carbon-cutting work and help them adapt to the impacts of climate change which are already proving deadly.

Climate finance is a question of reparations, Molly Scott Cato - a professor of green economics at Roehampton University, previously an MEP and reporter on sustainable finance - tells Euronews Green.

According to Scott Cato, it is “the money that has to be spent on recompensing the countries of the Global South for the damage that has been done to them, because richer countries have been pouring out carbon dioxide emissions for hundreds of years.

“So it’s that repair money. That’s really what climate finance is all about.”

How is climate finance being delivered? Grants vs loans

Each year, the intergovernmental Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) analyses the actual amount of money being provided by developed countries.

In 2019 the sum totalled $79.6 billion (€6.6 billion), and while official figures for 2020 are not available yet, it looks to have been at least another $10 billion (€8.7 billion) short.

Climate finance from a country like the UK or France can be bilateral (country to country) or multilateral (through international institutions) and can take the form of grants or loans.

One of the most contentious aspects of climate finance is the amount provided to developing nations in loans, which accrue interest. In effect, says Prof. Cato, “you’re charging them to repair the damage you’ve done to their countries through the climate crisis.”

Looking at the OECD report last year, Oxfam calculated that loans represented a staggering 74 per cent of public climate finance. Carbon Brief analysis shows that some of the countries with the largest contributions, like France and Japan, offer nearly all of their finance as loans.

In the COP26 draft text published this morning, the growing need of developing countries, such as Chad and Haiti, is acknowledged, with calls for “greater support to be channelled through grants and other highly concessional forms of finance.”

Put simply, we need to start handing out money with no strings attached, not just offering it to struggling countries on loan.

Public vs Private funding

The draft text also calls on the private sector to step up, and encourages countries to explore “innovative approaches” for mobilising finance for adaptation from private sources.

Prof. Scott Cato has noticed governments increasingly passing over the responsibility for green finance to private companies. But though that might free up more climate funds, what is the cost to democratic control?

One of the biggest financial announcements to emerge from COP26 so far is the creation of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, or ‘GFANZ’.

Led by UN climate finance envoy Mark Carney, more than 450 financial institutions wielding $130 trillion (€112 trillion) have pledged to set science-based targets to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Carney claims GFANZ “can unlock the $1 trillion of additional annual investment needed for the net zero transition in emerging markets and developing countries by the middle of this decade.”

Campaigners, including Greta Thunberg, were quick to denounce it as greenwash however, as the institutions are allowing themselves to keep investing in fossil fuels while buying carbon offsets.

Deciding the rate of divestment “is not a decision that the private finance sector should be making,” points out Prof Scott Cato.

“That's a decision politicians should be making.”

Avoiding ‘double climate injustice’

Climate justice demands that countries built on the back of coal and colonialism support those they exploited, to lower their emissions and adapt to a crisis not of their making.

But Scott Cato says there is a danger that the voluntary carbon markets and carbon offsetting pursued by richer countries will have a “colonial” hold over the same lands exploited during imperial times.

She describes the example of a finance company buying up land in an African nation and displacing farmers for a tree planting scheme to offset emissions in a global north country. Controlling the land in this way would be like “creating a second round of colonialism - but a financialised form of that.”

It would be akin to “a double climate injustice,” says Prof. Scott Cato. “If we exploited their land again, to offset our emissions rather than actually taking responsibility and reducing those emissions.”

We must watch the terms of climate finance, she adds, as well as who defines it and what it includes.

“If the people who actually live in the communities affected by what happens with that money are not consulted, then it could just add to the inequalities and power imbalances in a lot of the societies that are receiving it.”