Consuming invasive species "can turn this challenge into an opportunity... and help limit the environmental threat," says the EU’s Fisheries Commissioner.

Climate change and the opening of Suez Canal have in recent years opened the floodgates to invasive species in the Mediterranean Sea, where they threaten biodiversity.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Lionfish, with their red and orange stripes and antennae-like barbs, threaten to decimate indigenous fish stocks, wreaking havoc on the livelihoods of the roughly 150 professional fishermen in Cyprus.

"It leaves nothing behind and multiplies because it has no enemies. It is very dangerous for all fish in the areas where it multiplies and stays," says local fisherman Photis Gaitanos.

The prickly fish has even made its way as far north as the Ionian Sea, where Italian authorities have asked the public to photograph and report sightings.

The East Mediterranean has also seen another invasive Red Sea fish in the last decade: the silver-cheeked toadfish. Known as an eating machine whose powerful jaws cut through fishing nets, decimating fishermen’s catch, it has no natural predators off Cyprus, allowing its population to explode.

That toadfish also produces a lethal toxin, making it inedible.

Eating the problem: Lionfish grace the menus of local restaurants

Although no solution has been found for the toadfish other than subsidising fishermen for killing them, in Cyprus they have found a way to reduce lionfish populations while at the same time making a profit.

Once their venomous spines have been removed, lionfish have become a delicacy in the country's seafood restaurants.

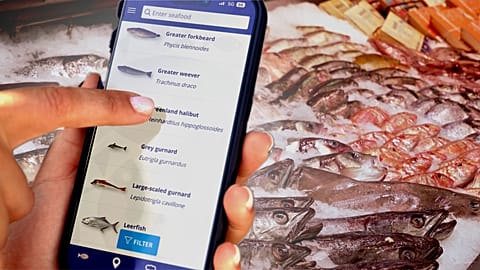

The European Union’s Fisheries Commissioner Costas Kadis, a Cypriot himself, says a social media campaign that began in 2021, #TasteTheOcean, had top European chefs and influencers plugging invasive species as a tasty alternative to the more commonly consumed fish. Renowned Cypriot chef Stavris Georgiou worked up a lionfish recipe of his own.

Although eating lionfish has been slow to catch on, many tavernas and fish restaurants have started to introduce it as part of their menu.

The bonus is that lionfish is now priced competitively compared to more popular fish like sea bass. At the Larnaca harbor fish market, lionfish cost less than half as much as more popular fish like sea bass.

“By incorporating invasive species such as lionfish into our diet, we can turn this challenge into an opportunity for the fisheries sector and at the same time help limit the environmental threat caused by these species,” Kadis says.

Stephanos Mentonis, who runs a popular fish tavern in Larnaca, has included lionfish on his meze menu as a way to introduce the fish to a wider number of patrons.

Mentonis, 54, says most of his customers aren’t familiar with lionfish. But its meat is fluffy and tender, and he says it can hold up against perennial tavern favorites like sea bream.

“When they try it, it’s not any less tasty than any other fish," he says.

"First of all it has to be cleaned, it is very dangerous," he adds. "You have to cut the spines off... if you get pricked, you will not die but it you be in terrible pain."

What's driving invasive species into the Mediterranean?

Gaitanos, the 60-year-old fisherman, has fished for years in an area a few kilometres off the coastal town of Larnaca, once famous for its bounty of local staples such as sea bream, red mullet or bass. Now, he says, it’s been more than two years since he’s caught a red mullet, a consumer favourite.

“I have been practicing this profession for 40 years. Our income, especially since these two foreign species appeared, has become worse every year. It is now a major problem [affecting] the future of fishing," he says.

The General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM) of the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) says with the sea warming some 20 per cent faster than the global average, the presence of non-indigenous species, including invasive ones, “is progressively increasing in the western basin”.

Models show that warmer seas as a result of climate change could see lionfish swarm the entire Mediterranean by the century’s end. Warmer waters and an expanded Suez Canal “have opened the floodgates” to Indo-Pacific species in general, according to Cyprus’ Fisheries Department.

Kadis says that more frequent and intense extreme weather, often linked to climate change, could make the Mediterranean more hospitable to invasive species.

And that’s taking a heavy toll on Europe’s fishing industry as fishermen’s catches diminish while their costs shoot up as a result of repairs to fishing gear damaged by the powerful intruders.

“The native marine biodiversity of a specific region, as in the case of Cyprus, faces heightened competition and pressure, with implications for local ecosystems and industries dependent on them,” says Kadis.

What's being done to curb invasive species in EU waters?

Gaitanos, who inherited his father’s boat in 1986, is not sure the fishermen’s grievances are being handled in a way that can stave off the profession’s decline.

“We want to show the European Union that there’s a big problem with the quantity of the catch as well as the kind of fish caught, affected by the arrival of these invasive species and by climate change," he says.

Some EU-funded compensation programs have been enacted to help fishermen. The latest, enforced last year, pays fishermen about €4.73 per kilogram to catch toadfish to control their number. The toadfish are then sent to incinerators.

Another project, RELIONMED, which began in 2017, recruits some 100 scuba divers to cull lionfish around wrecks, reefs and marine protected areas. The Cyprus Fisheries Department says surveys show that frequent culls could buy time for native species to recover, but it’s not a permanent fix.