How fire turned a goat herder into a climate migrant in 'empty Spain'

Álvaro had just begun his work as a goat herder when a virulent fire forced him out of a depopulated region that needs people to fight climate change.

A suspicious smell. A quick glance up at the peak of the mountain. It could just be a dark cloud. But it could also be smoke.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Álvaro García Río-Miranda, a 30-year-old goat herder, is haunted by fire.

As he herds his animals through the northern valleys of Sierra de Gata, a region isolated from the rest of Spain by a chain of mountains on one side, sitting against the Portuguese border on the other, he is trailed by paranoia.

The area is part of what is known as “empty Spain” – heavily depopulated rural areas that contrast sharply with the country’s thriving cities. In 2015 it suffered a devastating wildfire, triggered by the longest heatwave on record in the country. It is the memory of what happened that summer that follows García Río-Miranda through the valleys.

Unpredictable flames

“As much as you see it on television, until it happens to you, you are not aware of the power of fire," says Álvaro.

Between 6 August and 4 September 2015, more than 8,237 hectares of forest burned in Sierra de Gata, a region proud of its lush greenery and rich environmental heritage.

Experienced firefighters are usually able to predict the direction a fire will take. But in 2015, the flames took them by surprise, travelling erratically north then south with no discernible pattern.

More than 1,500 people – firefighters, police and medical staff – were mobilised. It was the largest deployment of these personnel in the history of the region. Around 2,000 people from three villages – Acebo, Hoyos and Perales del Puerto – were evacuated.

“The fire surrounded the whole village,” said Acebo resident Nati Alviz. She and her husband Jesús are goat herders. They say they were the last people to leave because they didn’t want to abandon their dogs.

Vanesa Caro, from Acebo, still cannot hold back her tears when she remembers that night, and the feeling of leaving her house without knowing if it would be there when she returned.

She and her family were used to having to leave their farm every summer because of the fires, but in 2015 she feared for their lives.

“We were in a line [of cars] and the fire was on the side of the road, the only road we could get out on,” she recounts.

Álvaro had only bought his herd, which he housed in a warehouse in Acebo, six months before the fire. When your family is not in the farming business, the beginning is tough, he explains. For him, being a goatherd was “a passion and a way of life,” and there was no better place than Sierra de Gata to start this kind of business.

You don't have to pay to use the area’s pastures, there is little competition and you can take your goats wherever you want, except over vineyards and olive groves, he explains. And the rocky landscape is perfect for goats.

When he thinks of the fire he remembers running for days, frantic, disorientated and not knowing how or where to keep his animals safe.

Climate migrations in Spain

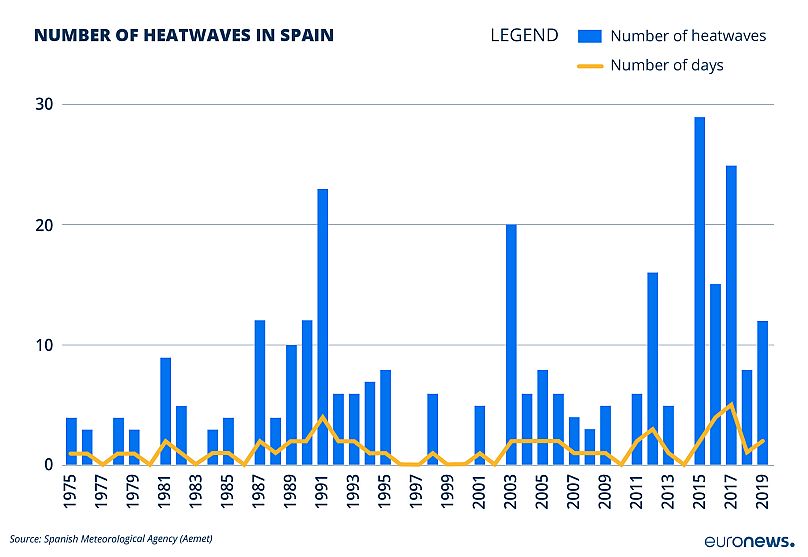

There are more than 100 small fires on average in the region each year. What made the one in 2015 so destructive was a record-breaking heatwave, explains Marcelino Núñez of the Spanish Meteorological Agency (AEMET).

It was the longest ever recorded in Spain, lasting 26 days compared to the average, of one week. Almost a month without a break from relentless heat made it impossible for the forest to recover its humidity and break what became a vicious circle, explains Núñez. “Under these circumstances, anything can ignite and it is almost impossible to extinguish it if the wind blows.”

Álvaro says with certainty that climate change was behind his leaving Sierra de Gata in 2015. “Many factors came together, but an important one was how the climate was evolving,” he says.

Spain was the European country with the largest number of climate displacements in 2019, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center (IDMC). This year began with storm Gloria, which ravaged the eastern coast, killing 14 people and displacing 500.

In the country, this displacement has been mostly temporary, with most people able to return to their homes. But some, like Álvaro, cannot afford to rebuild their lives from the ashes.

The wildfire left him unemployed after it killed his goats. While they did not die in the fire, the stress it caused them and the lack of food and change in routine saw his herd halved within a month. “They’re very fragile animals,” he explains.

Álvaro couldn’t afford to insure his herd, so the losses overwhelmed him. He had to sell his remaining goats and everything else he owned, and leave in search of a new way to make a living. He ended up working as a shepherd in France and Switzerland, taking care of other people’s herds.

He was not the only one to leave. Other farmers lost their crops and animals, while some residents of Sierra de Gata who had been similarly affected by a virulent wildfire in 2003 simply felt unable to rebuild again.

Vanesa, who stayed, said: “When there is already depopulation, you almost don't notice the difference. But I know for some people the fire was the culmination of the decision to leave.”

Others who stayed faced dire consequences. The burnt landscape made feeding livestock difficult in the years that followed. “There are no trees to give us shade and you can feel it in summer, it’s way hotter,” says goatherd Nati. “It also rains less.”

She is proud that she and her husband stayed put against the odds. “If we had given up [after] the fire, we wouldn't be here today with the goats and maybe we wouldn't be living in the village.”

Depopulation and climate change: A time bomb

What happened in Sierra de Gata showed how southern European regions are increasingly vulnerable in the changing climate. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns the expected rise in temperature will make extreme weather episodes in the Mediterranean region worse, with more pronounced droughts and longer and more intense heatwaves – which will mean drier vegetation ready to burn.

“The number of heatwaves is not increasing much because we are already in one of the hottest areas of Europe, but we do notice that they are becoming more intense and lasting longer,'' says Nuñez.

In Sierra de Gata, this means increasingly long summers, a lack of water and poor harvests. As a region emptied by migration to cities, it is extra vulnerable. “Empty Spain'' constitutes 53 per cent of the country’s territory, inhabited by 5 per cent of its population.

"Depopulation and climate change together are a time bomb," says Óscar Antúnez, mayor of Hoyos. A native of Sierra de Gata, he remembers ice on the streets when he was in high school. He says neither the rain nor the cold are the same now.

“Here, mountains do not have virgin forests. It is a humanised landscape that has been modified over thousands of years,” says Carmen Hernández Mancha, a local environmental journalist. “In order for it to be healthy and resist climate change and fires, it needs people living there.”

Rural abandonment generates uncontrolled growth of forest masses that lead to more fires, explains Professor Fernando Pulido of the University of Extremadura. He is in charge of the Proyecto Mosaico – an initiative aimed at encouraging people to move to the area and start environmentally friendly businesses that will help prevent fires. Ironically for Álvaro, shepherds are on the list of desirable entrepreneurs, as their animals help keep clear the mountains’ firebreaks – gaps in vegetation or other combustible material that act as a barrier to slow or stop the progress of wildfire.

"What we propose is to attack the fires from the root of the problem,” says Pulido. “If the fires are caused by depopulation or lack of activity in the mountains, then we should generate activity in the mountains.”

Building a more resilient society

“We’re trying to attract young people to come to live here. It’s an area where people live well. But there’s no work,” says Rodrigo “Bongui” Ibarrondo. “Many leave because they’re young and looking for work.”

Bongui uses the word "opportunity” to talk about the fire. In the aftermath, he initiated a programme to reforest the burnt areas with a variety of trees more resistant to fire – oaks, chestnuts, cork oaks, holm oaks, strawberry trees.

He wants to recover the native forest of the region that has been repressed by dominant pine monocultures for decades. “The major fires exist where there are monocultures,” he claims.

More than a thousand volunteers from 45 countries have already come to the region to help. They stay in a hostel in one of the villages, where they meet the locals.

Depopulation is a vicious cycle – the more people leave, the less others want to come or to stay. It’s not easy to be young in these villages of Sierra de Gata, some of which have only 70 inhabitants, says Carmen Hernández Mancha, especially in winter when the streets empty. “One winter you can get through, but one after another, after another...People need governmental aid [in order] to stay”.

“This isn’t charity, it’s about getting things done,” Bongui says. He agrees that the government should help those who want to raise goats or open a dairy, “instead of putting up obstacles”.

Jill Barrett, who is English, says she had to jump bureaucratic hurdles to open her eco dairy, where she produces cheese, in Sierra de Gata. She says there are plenty of existing aid programmes from the government, but none that are really useful – or easily accessible.

“I'm a graduate, and the paperwork overwhelmed me,” she said. “I think the system should be clear enough for the [individual] to be able to handle it alone.”

Another obstacle to settling in the region’s villages is that there is no culture of renting. “I think that people who come here want to rent but people who have property prefer to sell and there is a bit of conflict,” explains Jill. “I know three young couples who had to leave because they couldn't find housing. It's a bit ironic because we are fighting against depopulation.”

Back to pack

Jill’s cheeses are made with milk from Álvaro’s goats. After years away, he returned to the valleys of the Sierra de Gata with a new herd, his wife and their baby daughter.

Last summer was “horrible,” he says, too hot. He thought about taking his goats north for the summer to higher, cooler grazing grounds, according to the traditional seasonal, cyclical method, but now that he has a family, living as a nomad is no longer an option, he says. For him, the entire way of life for a goatherd in Sierra de Gata is “economic suicide”.

So he is selling his goats and heading back to Switzerland to take care of someone else’s herd – this time for good. One fewer young family for Sierra de Gata, one fewer herd to keep its firebreaks clear.

This article was originally published in March 2020.