Extreme weather exiles: how climate change is turning Europeans into migrants

In this exclusive series, Euronews tells the stories of Europeans forced to leave their homes because of climate change, and of those who chose to stay despite the risks.

Climate change could leave you homeless overnight – right here, in Europe.

Flash floods, mudslides and wildfires triggered by heatwaves are among the extreme weather events becoming increasingly common, thanks to climate change.

Those who lose their homes and livelihoods in these disasters run the risk of being displaced, and becoming climate migrants – just like Iris, or Anne and Jean or Álvaro, Magdalena, Ana and Zekira or Julie and Chris, the people you will meet throughout this series of articles and videos. People whose stories have so far remained unreported.

“It’s a reality in Europe, not something that will happen in centuries,” says Dina Ionesco, who leads the work being done on migration and climate change at the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

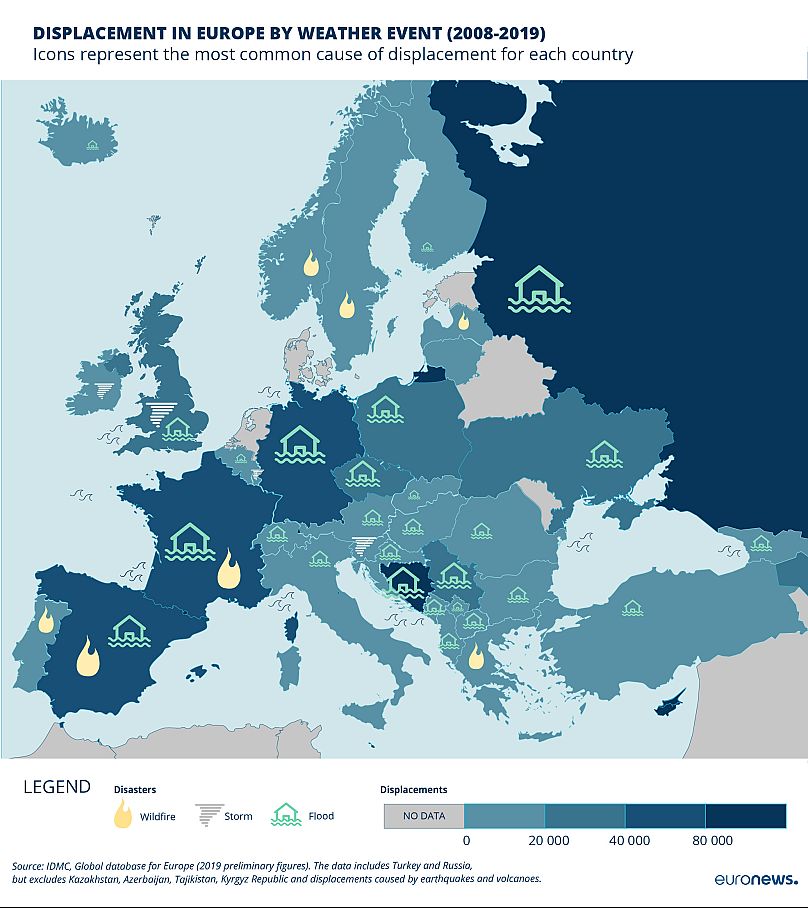

To find Europe’s environmental migrants, we travelled to the countries that have seen the highest number of displacements due to climate events on the continent, according to data provided by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC): Bosnia and Herzegovina, Spain, France and Germany.

We also went to Moldova – ranked as the most climate-vulnerable country in Europe – and to Portugal, the European country with the highest annual number of wildfires since 2015.

“Disaster displacement is very much a global phenomenon, even in high- income countries like the ones in Europe,” says Alexandra Bilak, director of the IDMC.

More extreme weather events, more dangerous, more often

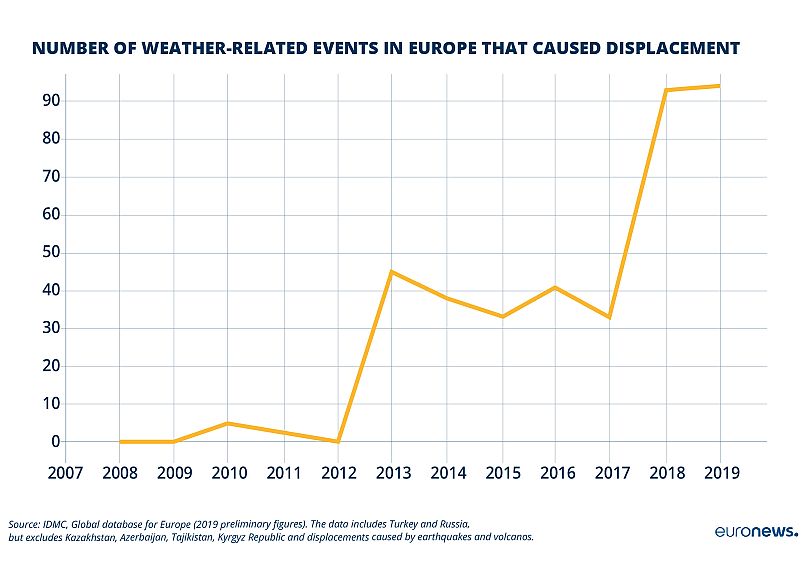

Climate events causing displacement in Europe have more than doubled in the last four years, from 43 in 2016 to 100 in 2019. By February 2020, four storms – Gloria, Brendan, Ciara and Dennis – had already wreaked havoc on the continent’s northern and western coasts.

The science is abundantly clear – climate change aggravates extreme weather events, making them deadlier and increasing the chance of them becoming more widespread. “Our climate projections show that the events that we are now classifying as extreme will become more frequent in the future. They will become the new normal,'' says Gianmaria Sannino, head of the Climate Modelling Laboratory at the Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development (ENEA).

Every number hides a human story

For every disaster in Europe that becomes a database entry, there are people who have lost everything. Most manage to rebuild their homes and return. But some are not as lucky.

Statistics show there are more heatwaves in Spain now than ever before. In the last five years, they have lasted an average of 15 days each. Between 1975 and 2014, Spanish heatwaves typically lasted for about five days.

Numbers like these become the backdrop for stories of people like Álvaro García Río-Miranda.

In 2015, the 30-year-old goatherd had just begun working in the valley of Sierra de Gata, near Spain’s border with Portugal, when a wildfire killed half of his herd. Like many young farmers in Spain, Álvaro García Río-Miranda had been unable to afford insurance for his goats. He decided to sell the ones that survived, and moved abroad to find work.

The fire in Sierra de Gata was fuelled by the longest heatwave ever recorded in the country. The goatherd remembers: “I was running with [my animals] for four days. I didn’t know where to put them. They almost got burned alive in the village. Until it happens to you, you don’t understand its power.”

In other parts of Europe, flash floods have begun to strike places we might not have seen as vulnerable.

In 2010, La Faute-sur-Mer, a sleepy retirement town on France’s Atlantic coast, was devastated by a flood aggravated by the rising sea level. The water killed 29 people and displaced hundreds. Elisabeth Tabary lost her husband and grandson when her home flooded in the middle of the night.

One man lost his mother, his wife and two sons that same night. While Elisabeth stayed, reluctant to abandon the place her family called home, he has never returned.

700,000 displacements in Europe in the last decade

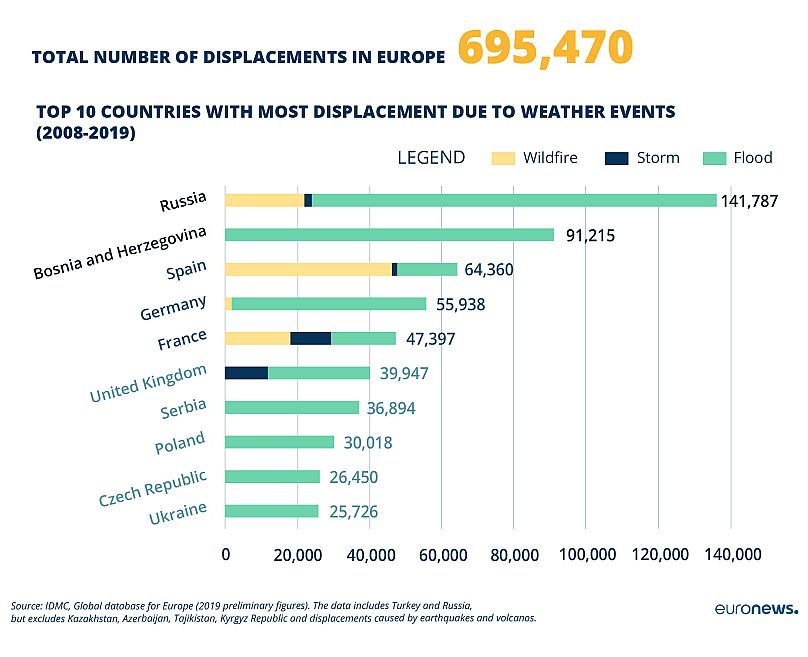

There have been 700,000 such stories of loss in Europe in the last decade. Avalanches, storms, floods and wildfires – by nature – often hit the same locations multiple times.

“I'm not sure that only one episode promotes population displacement,” says Yves Tramblay, a scientist at the French Institute of Research for Development who specialises in hydrological hazards. “However, I think if these episodes repeat in the same areas that are frequently affected, they can actually push people to relocate elsewhere, if they have the possibility”.

After a few years abroad, the young goatherd Álvaro gave Sierra de Gata another chance and returned with a new herd. But the constant threat of fire made him paranoid every summer. Knowing he could not live through another one, he has decided to leave for Switzerland – this time for good.

Would you call yourself a climate migrant?

The impact of climate change in Europe is a recent enough phenomenon that it does not occur to most climate migrants that that is what they are. Nor is there an official definition. Beatriz Felipe, a Spanish climate migration researcher, says: “In reports, studies and scientific articles you find that different definitions are used: displaced persons, refugees, migrants. This leads to a great deal of confusion."

The 2009 UN convention to combat desertification found that migrants also tend to underestimate climate as a factor in their situation. Most explain their displacement in terms of poverty, often overlooking the root cause behind the deterioration of their homes and land, and the resulting loss of productivity.

“Even for those cases in which it is very clear that climate impacts are directly driving people's migration – such as severe drought – people will hardly acknowledge that”, says Felipe.

After a catastrophic flood in 2014, Ana, a Bosnian woman who didn't want to use her real name, moved from Domaljevac, a small town on the border of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia, to Germany.

When the river Sava broke levees after three weeks of torrential rain, 98 per cent of her hometown was submerged and her newly built house was destroyed.

“These events changed me profoundly, even though I always wanted to stay and live here”, she says over the phone from her home in Frankfurt, where she joined her husband with her son. “The floods made me think about what I would be able to offer my child in that village, in Bosnia, in two, three or 10 years’ time.”

However, she says she is not sure that the floods were her reason for moving abroad. She thinks they were “the cherry on top in our decision-making process”.

The fact that migration after an extreme weather event can seem, and even feel, voluntary, particularly when the migrants in question have the choices that come with economic means, adds to the lack of clarity. As an IOM report states, environmental migration is sometimes forced, sometimes voluntary, more often somewhere in between.

How can you prove persecution by climate change?

Use of the term “climate refugee” creates a lot of buzz, according to Maeve Patterson of the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), “but also a lot of confusion, as it doesn’t exist in international law.”

It is necessary to demonstrate persecution on the grounds of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership of a particular social group in order to request refugee status. “But you cannot show persecution from climate change,” says Ionesco, of the IOM.

She says there is currently an international debate over the necessity of differentiating climate refugees from climate migrants. The IOM’s position is that opening up the 1951 Refugee Convention to include climate change-related flight could weaken the integrity of the existing refugee status.

Ionesco believes that existing migration policies – such as temporary protection given to someone who crosses a border because of a natural disaster – can be part of the response.

While refugee status is also dependent on the individual having crossed a border, Patterson points out that climate change “typically creates internal displacement before it reaches a level where it displaces people across borders”.

In most countries, relevant laws on internal displacement, if they exist at all, are focused on the consequences of conflict – as is the case in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Its laws were developed following the Dayton Agreement, the peace accord that put an end to the Bosnian War. While some of the principles apply to disaster displacement, it has been largely neglected in domestic law.

The legal challenge

Many of the climate migrants we interviewed told us that a natural disaster was one among many factors that brought about their decision to leave home. This is typical of of most climate migrants’ narratives. This makes climate change tricky to isolate as the sole driver behind migration, which makes it difficult to hold it up in court.

“If you are exposed to a chemical product and you get cancer, you will have a hard time saying in court that the cancer was produced by the chemical agents,” says Corinne Lepage, former French environment minister and the country’s most high-profile environmental lawyer. Lepage represented the victims of 2010’s Storm Xynthia in La Faute-sur-Mer when they successfully sued the town’s mayor.

“It is [sort of] the same thing for climate: even if there is a strong presumption, it is very difficult to prove that [these] things would not have happened otherwise.”

Lepage says the case of La Faute-Sur-Mer should be a lesson in climate change law, adding that there is work to be done, given the lack of existing legislation in France to cover increasingly common climate-related disasters.

In this field, Europe as a whole lags behind Africa. The African Union has adopted the comprehensive and legally binding Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa. Also known as the Kampala Convention, it acknowledges climate change as a man-made disaster creating displacement. The EU has no such equivalent region-wide convention.

“Except Finland, Italy and Sweden, no [European] country has a climate element in their protection system,” says Jean-Christophe Dumont of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). He adds that this makes an EU legal framework for environmental protection very difficult.

The Moldovan example

Moldova, the poorest country in Europe and the most vulnerable to climate change, lacks a clear definition of internally displaced persons in its legislative framework.

Laws governing migration in the country focus on refugees and asylum seekers and the term “displaced persons” refers only to foreigners.

Asked about the need to adapt the country’s policies to include climate change, Moldova’s president Igor Dodon told Euronews: "The issue is not that of one country or nation, but a global one.” He said there were several plans to mitigate its effects in his country, but did not mention any specifically.

According to the UN, Moldova suffered eleven droughts between 1990 and 2015, costing the country more than €1 billion.

The true scale of an under-reported phenomenon

Studies and reports in recent years have joined the dots between migration, climate change and environmental degradation. However, all of them cite Europe only as a “recipient” in these migration patterns.

“In the common imagination, migration flows only come from Africa or from developing countries,” says ENEA scientist Sannino.

The difficulty in tracking voluntary (if under duress) movement of people from one European country to another, like Ana’s migration from Bosnia and Herzegovina to Germany, leads to widespread under-reporting, both by the media and academic institutions.

“Even if there are much higher levels of preparedness in European countries than others, there’s actually less information available,” says Alexandra Bilak of IDMC. “Not just about the number of people becoming displaced every year, but also about what happens to them in the long run.”

The area is clearly under-researched, admits the OECD’s Dumont, citing reasons from the relatively small scale of displacements to the absence of official reports on the return flows after a disaster, and the lack of legal definition at national and international level.

A question of economics

“We fear disaster displacement risks exacerbating socio-economic inequalities,” says Bilak. She explains that lower-income families are disproportionately exposed to such disasters and are at greater risk of being displaced by them, and remaining so for longer periods of time.

In central Bosnia and Herzegovina, many of those affected by the 2014 flood were older people living off an annual pension of €2,500. Mudslides demolished their houses, causing €50,000 of damage in some cases, making any recovery utterly unaffordable.

The UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, Philip Alston, believes humankind is heading towards what he calls "climate apartheid".

“We’re concerned that many low-income households are buying cheaper land to build cheaper houses in areas that are going to be more vulnerable to these types of events in the future, and therefore this pattern of poverty and vulnerability will only be perpetuated and exacerbated by these events in the future”, says Bilak.

However, even in Bavaria, south-east Germany, one of Europe’s wealthiest regions, some residents cannot afford to insure their houses against the effects of climate events. It took pensioner Karl Bretzendorfer more than six years to rebuild his home after the floods of 2013. If the floods come again, he won’t get financial aid to do so – in 2019, Bavaria’s regional government stopped public economic support for victims of natural disasters who don't have home insurance. Insurance would cost Karl Bretzendorfer €1,000 a year. His only income is his pension – €850 per month.

As climate change-related events become more frequent, the capacity to support its victims economically will be a challenge for European governments.

“I think that the problem today is a problem of cost, because in France most of the work to protect houses against the sea, home repairs and compensation are covered by the public sector, and I think that we are reaching the end of [the line with that] system,” says Catherine Meur-Férec, an expert in coastal geography at the Université de Bretagne Occidentale.

“Even though the primary responsibility has to rest with national governments we do think there could be an increased role to play by the private sector and by insurance companies,” says Bilak.

Where do Europe’s climate migrants go?

In most cases, displacement due to climate change occurs within the affected country's borders. But despite being forced to abandon their homes and livelihoods, the internally displaced “are often the most forgotten and neglected people in the many forgotten and neglected emergencies around the world,” according to Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, a set of international principles all countries are bound by under international humanitarian law.

After the tragedy of Xynthia, Anne and Jean Birault lost their home in La Faute-sur-Mer. Unlike many other Europeans, they were compensated by the French state and decided to move 30 kilometres away, rather than live with the fear that another storm would hit them as they slept.

But for them, it is not a matter of distance. They say money cannot buy back what they lost when they left their home and the memories of the family they raised there.

Many victims of extreme weather events are forced to move in with family in the aftermath, some having to cross borders to do so. Ionesco explains: “Very often, people are already in a migration story that is very complex, with parts of their families living in different countries.”

“A friend of mine was picked up on the day of the floods by her husband,” recalls Ivana (not her real name), a Bosnian nurse from Domaljevac. “He came for her from Germany, she got in the car and left. And her house wasn’t even flooded. For her it was simply a trigger to leave and never come back”.

According to Ionesco, the discussion at international level has to be not just political but also technical, involving, for example, how the right consular services can be made available to those who move as a result of a climate change-related event.

Bilak echoes this, saying: “It should be up to national governments, as first responders, to start with data collection, with monitoring this situation over time and then putting in place the right kind of systems to either relocate or compensate people.”

Towards a new urban exodus?

Rural areas are by nature more vulnerable than cities to climate change, given that “human economic activities are more linked to the land, which is being affected by floods and droughts,” says Spanish researcher Felipe. “In the end, if the land no longer [provides], people have to adapt or move.”

Bilak points out that, as a result, people living in rural areas will tend to flee towards urban areas, and that enabling cities to be better prepared for this flow of people has to be a priority for the future.

In addition, depopulation of rural areas and vulnerability to climate change are mutually reinforcing processes.

The lesson learned in the Spanish region of Sierra de Gata after the 2015 fire can be applied across Europe. “Here, mountains have no virgin forests. It is a humanised landscape that has been modified over thousands of years,” says Carmen Hernández Mancha, a local environmental journalist. “In order for it to be healthy and resist climate change and fires, it needs people to live there.”

The emotional legacy

When the 2011 tsunami hit Japan a year after the flood that destroyed her home in La Faute-sur-Mer, Anne Birault "started shaking from the top of my head to my feet”.

In Portugal, Julie Jennings and Chris Nilton, British pensioners who survived the 2017 wildfires in Pedrógão Grande, are now packing up and migrating to the coast. Julie cannot live with the rising heat in the region, and memories of the fire haunt them at night. As they pack their belongings, they talk of not being able to sleep, and feeling anxious and scared.

After losing everything in the 2013 flood in Bavaria, Iris Hirschauer decided to move with her family to a neighbouring village to avoid a repeat of the trauma they had suffered. “We never want to be evacuated again and have to lean on strangers,” she said.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, 68-year-old Šefik Čolić lost his house in the 2014 mudslides and was relocated three times before finally settling in a run-down town a few kilometres from his home. He says that he and his wife “needed psychological assistance for a while”.

Uprooted: the challenges of relocation

In 2012, France developed a national strategy on the possibility of relocating coastal communities deemed to be at risk. “But there is very strong resistance at the local level, even with the right compensation,” says Catherine Meur-Férec of the Université de Bretagne Occidentale.

“In France,” scientist Freddy Vinet, expert in disaster management, explains, “we are in a culture where people are very attached to their private property, to their land and their house. There is no tradition of mobility.” He says the conversation is about places where generations of families have lived, died and been buried.

“We know sea levels are rising, so the real issue is, how do we [retreat from the coast] and reconstruct our lives with the minimum social and economic impact? We have absolutely no means to finance a mass-coastal retreat”, says Laurent Huger, deputy mayor of La Faute-sur-Mer.

Some communities resist moving at any cost.

In Cotul Morii, a Moldovan village on the border with Romania, we met families that have been living in a ghost town for more than a decade. After a catastrophic flood, Moldova’s government built them new houses in a village 15km away, but they refused to leave their homes.

“Very little has been said about those who can’t migrate, because they have no resources, and about those who do not want to leave,” says Felipe. “Within the planning of relocations, the rights of people who don't want to leave have to be taken into account.”

An opportunity to build more resilient societies

According to Felipe: “In Europe we have the technical and economic possibilities to adapt to climate change. We are only lacking political will.”

Bilak adds that European governments still need better flood-risk mapping and policies, and to work on compensation mechanisms to ensure that displaced residents can either return to their homes safely or build elsewhere, in safer areas.

After extreme weather events, governments often rush to announce that everything has been rebuilt exactly as it was, reassuring their populations that the status quo has been restored. In Serbia and in Bosnia and Herzegovina, river banks were not raised any higher than they were doing the 2014 floods, says Vladimir Djurdjevic, a climatologist at the University of Belgrade.

“They don’t realise that, since we have to expect more floods, and bigger ones, when you reconstruct things the way they used to be, you are not protecting people from future impact.”

But more resilient communities can rise from the ashes. When you ask residents of Sierra de Gata about the aftermath of the 2015 fire, many use the word "opportunity”.

One local man, Rodrigo "Bongui" Ibarrondo, initiated a programme to reforest the burned areas with tree species more resistant to fire. “The landscape was crying out for a change and what is clear is that the pine monocultures were the factor that made the fires happen at that magnitude,” he says.

In La Faute-sur-Mer, deputy mayor Huger says: “We have created a network that, in case of a storm, has an obligation to look out for older or disabled neighbours.”

In Moldova's capital Chisinau, it is difficult to find younger people who believe climate change is impacting their lives. But just under 100 kilometres to the west, in the remnants of the small town of Cotul Morii, which was swallowed up by floods in 2010, the elderly residents are all too aware that it is.

Ion Sandu, 85, wrote a poem in 2017 upon waking up and seeing snow outside – in April.

The village he lives in no longer officially exists.

Winter comes on the eve of May

And it settles on my homeland

Winter comes in April

And it only brings us cold

What fault would it be

Of a small tulip

That lies under the snow

Wanting a bit of warmth

And the trees blossomed

A rich harvest announced

One night it all froze

What a tragedy

Maybe the climate has changed

Or maybe the world is broken.

Sandu's house had flooded during the 2010 storm. He and his wife, who has since passed away, were evacuated by the army. When the government offered him a home in the new village it had built for those affected by the water, he refused to leave the house he had lived in all his life. He had inherited it when his parents died, and promised his father he would take care of his vineyard.

If the house floods again, he will not be evacuated – the village he lives in no longer officially exists.