Many see visual art and hard science as completely separate fields, but are they? Here we take a look at artists who embrace both worlds.

In 1990 physician Frank Meshberger published a paper with an intriguing theory – that Michelangelo’s 'The Creation of Adam', sat on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, carried a secret message.

Meshberger insists that the shroud surrounding God as he reaches out to touch Adam’s hand is in the shape of a human brain, a shape the artist would have been familiar with after supposedly seeing illegal dissections during the renaissance.

But art historians aren't so sure.

“The idea that there is a hidden brain is nonsense,” says Martin Kemp, Professor Emeritus of the History of Art at the University of Oxford.

“If you look at the brain as it was understood at the time it doesn’t fit at all.”

However, to think that a famed artist was also dabbling in science during the enlightenment is an enticing idea.

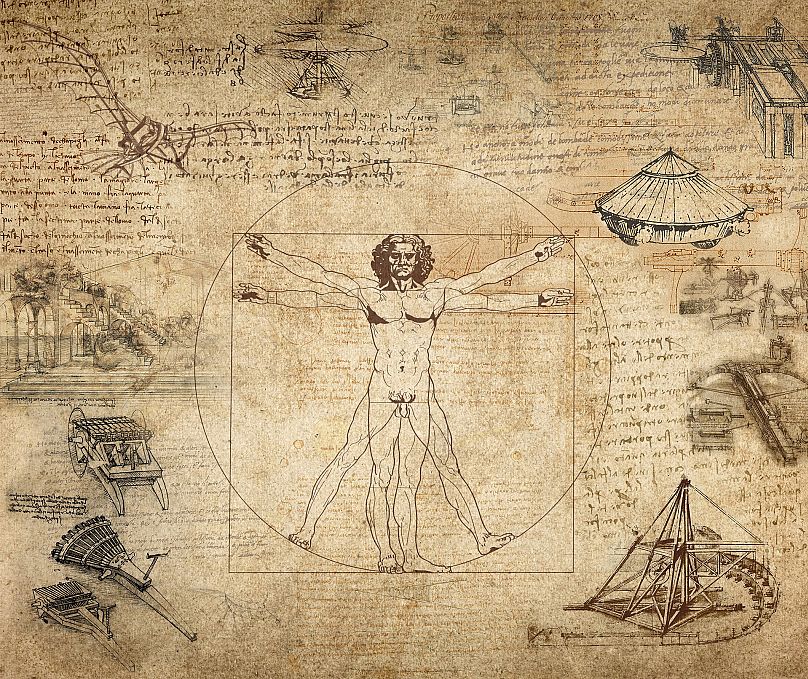

In fact, many celebrated artists have also had a finger in the sciences, and vice versa. Leonardo Da Vinci’s 'Vitruvian Man' was both an artistic sketch and an exploration of anatomy, meanwhile Isaac Newton drew mechanical sketches on the walls of his home.

So why, in contemporary society, do we see visual art and science as so distinct from one another?

Science communication: Where two fields merge

Professor Kemp believes that they may be more closely aligned than many believe.

During the renaissance the visual arts aspired to represent objective knowledge and the sciences followed. Then as Einstein questioned the orthodoxies of time and space in the 20th century, so came the revolution in shape and colour by Picasso and the Cubist movement.

“A scientist looks at a phenomenon in nature and they get a sense there is something worth explaining,” says Kemp.

“An artist looking at things…in nature. They don’t analyse that in a scientific way but they start at the same sort of point.

“They both begin from that starting point but what they do is very different.”

Using art to place our world under the microscope

Amsterdam boasts an art gallery which aims to close the gap in the public knowledge of the world’s most powerful unseen beings – microbes.

Micropia, which has been educating visitors for five years, provides visual exhibits which help visitors to understand microscopic creatures.

The museum has offered a wall which would enable people to understand how many microbes were on their hands, and stunning models which allow visitors to see the structure of viruses.

Artist Luke Jerram has made glass sculptures which were exhibited at Micropia as well as the German Hygiene Museum and the Eden project. His work shows the minutiae of ebola, HIV, malaria and COVID-19.

“As an artist I’m very interested in how the world works,” says Jerram.

“Historically artists and scientists were often the same people doing investigative work…it’s only over the last couple of hundred years that the two fields have diverged.”

In 2020, Jerram created a sculpture of an Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine nanoparticle to celebrate the ten millionth COVID vaccination in the UK. The sculpture was made from the same material as scientific glassware and was 1 million times the size of the actual particle.

He believes that a growth in the need for scientific communication has been necessitated in recent years in order for scientists to gain funding. Jerram has been commissioned to help with this work, even gaining an honorary title from the University of West England for a diesel particle sculpture he made to explain their air pollution research.

His work is widely respected – but does he feel like he’s walking a tightrope?

“I think I’m valued in the scientific community for my work in science communication, and then vaguely respected in the art world as well,” he explains.

Deconstructing science with art

In a demonstration of how the two fields become intertwined in unexpected ways Jerram’s sculptures now appear in textbooks to explain virology.

Artist Shannon Bono works to deconstruct assumptions about anatomy found in textbooks that are rooted in a colonial mindset.

“You have to think about how the world works,” says Bono.

“Medical students learn about the body through text book illustrations or digital animations”

Bono, who is an associate lecturer in Art and Science at Central Saint Martins, expresses narratives of black womanhood in her work.

Merging structures from inside the body and colours from African fabrics she creates narratives of everyday and extraordinary experiences.

“I enjoy telling the story of what’s happening on the inside as well as the outside”, she says.

After a year of studying biochemistry at university Bono realised she would never be a biochemist, however she took some of the patterns she'd seen in her biochemistry lectures and textbooks with her into her chosen field of visual art.

Using bodies to tell a story – the same way a medical textbook would inform a reader about anatomy – is how Bono works. Borrowing from religious iconography as well as cell structures along the way, all the while she’s highlighting the history of black bodies, especially their role in science.

She says her main focus was "figuring out the harsh history of how black bodies were treated as scientific objects and were used to confirm this idea of white supremacy.

“I wanted to understand how a lot of scientific breakthroughs were made through experimenting with black bodies.”

Maybe Michelangelo wasn’t secretly telling us what a brain looks like, but that doesn’t mean that exploring scientific ideas aren’t being explored in the contemporary art scene.

As Jerram says, the fields have become distinct over the last few centuries, but maybe the tide is turning.