We speak to Transport & Environment on how the innovation that will make flying green is being held back by government policy.

The aviation industry is happy to discuss its efforts to reduce the emissions of flight, but just how effective will its efforts be without the help of serious government policy?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Three of the most popular ways considered to reduce emissions in aviation are carbon offsetting, sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), and the creation of new technology like hydrogen-powered planes. For each of these, there is ambition and optimism technology will have the capability to change the industry.

But innovation is expensive and without the commitment of public funds, it could be unattainable. So what’s stopping governments from investing?

To find out more, Euronews Green spoke to UK policy manager for Transport & Environment Matt Finch about why critical emissions goals for airlines can only be reached with more proactive public measures.

Making carbon offestting cheap and effective

Carbon offsetting schemes are often popular with companies hoping to show that they are taking climate change seriously. But for a number of reasons, the schemes can be closer to greenwashing than a serious attempt to solve the problem.

The Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) began this year and has been adopted by 65 countries. Adoptees of CORSIA commit to only having carbon neutral growth in the aviation sector after 2020.

Global commitment to CORSIA is crucial to stopping the aviation industry's unsustainable growth. But so far the scheme is only voluntary until 2027.

Transport & Environment (T&E) is concerned that the price airlines are being asked to pay to offset their carbon output is not enough to meaningfully reduce the carbon in the atmosphere.

“I think it’s absolutely greenwashing,” Finch says.

He explains that while the price airlines are being encouraged to pay is enough to encourage airlines to buy in while it is still voluntary, it won’t actually offset the equivalent carbon the scheme claims it will.

To actually offset that amount of carbon, there would need to be greater investment in the direct air capture (DAC) industry which is more effective at removing carbon.

At around 500 times the price, however, it is currently too expensive for it to be financially viable for airlines to commit to.

“It needs to be encouraged at government level, it would be foolhardy to expect that to be something the private sector would invest in for its own sake, because it's too expensive,” Finch says.

Is sustainable avaiation fuel the answer?

The most immediately promising way the aviation industry will reduce its emissions is through Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF).

SAF can be made from plant and animal oils as well as the recycled waste from people’s homes. It is then refined and turned into a fuel that can be used in planes just like kerosene.

Because SAF is not sourced from fossil fuels, it reduces the carbon life cycle of the fuel by up to 80 per cent.

SAF production is an immediate goal for anyone in the aviation industry who’s concerned about climate change. But many worry that it’s being held back by a lack of encouragement from governments.

“SAF is in very low production today,” says Anders Fagernæs, vice president of sustainability at Norwegian.

“Only 0.05 per cent of the total fuel consumption in 2019 was SAF,” he explains. “That’s a tiny proportion, and it's also very expensive. It’s about three to five times more expensive in a very competitive market where the fuel cost is up to 30 per cent of an airline's total cost base.”

High costs for private companies are a concern for the whole industry.

“At the moment, production of SAF is limited as the higher cost for SAF is preventing wider uptake,” adds Andreea Moyes, Global Aviation Sustainability Director for Air bp, one of the main companies working to develop SAF.

“There is real commitment from the industry to reduce carbon emissions, but governments also need to create the right policies to accelerate the growth of SAF,” she explains.

“Increasing production requires long-term policy certainty to reduce investment risks, as well as a focus on the research, development and commercialisation of improved production technologies and innovative sustainable feedstocks.”

Are the SAF commitments enough?

Finch also raises concerns about countries’ commitments to SAF policies. Mandates for the EU and the UK for the proportion of SAF to be used by 2030 is just 10 and five per cent respectively.

“Airlines will still be burning 90 or 95 per cent fossil kerosene. There’s really not that much change on what there is today,” he says.

Even as far as 2050, the EU proposal for SAF is just 63 per cent.

A kerosene tax

If there aren’t going to be strong commitments to SAF mandates, Finch wants to see at least some taxes levied at fossil kerosene to encourage profit-seeking airlines to consider SAF more.

“Airlines will always talk about staff, but they'll never talk about the other way of reducing the price differential, which is increasing the price of fossil kerosene.”

Unlike other fuels, aviation kerosene is exempt from taxation. Currently the EU commission is considering a proposal to tax it but the UK has no immediate intentions to follow suit.

Taxing fossil kerosene and prioritising SAF production would also mean benefits for non-oil producing countries as they wouldn’t have to rely on the fluctuating prices from Russia and the Middle-East.

“It would mean more energy security,” Finch says. “And if you want to make SAF on UK shores, the money stays in the country, simple as that.”

Are hydrogen planes the future?

Many within the aviation industry consider hydrogen or electric powered planes a pipe dream. But Finch sees it as the natural end point of a journey that has to start with SAF.

“If you use SAF, you can get the carbon to net zero, but you still have nitrogen oxides, you still have water vapour, you have some contrails, you still have some of the non CO2 effects that also cause warming,” he says.

“Whereas if you go down to a hydrogen fuel cell providing again the hydrogen can be fully green.”

But government policy again needs to reflect the industry’s capacity to develop these new green technologies.

“The problem is most emissions come from long haul flights and there's absolutely no way hydrogen fuel cell planes will replace long haul flights in the next 30 years.

He says that even if we start now, with very small flights carrying just a few people, planes will eventually get bigger and go further.

“And suddenly we’ll reach that sweet spot for the UK at least where a lot of people fly between one and 2,000 kilometres because that's their holiday to Europe and all of a sudden you can replace a lot of planes,” Finch explains.

Finch says SAF is a crucial stepping stone to reduce emissions as fully green flights won’t be possible in the next few decades. But that should encourage investment in the technology, not dishearten it.

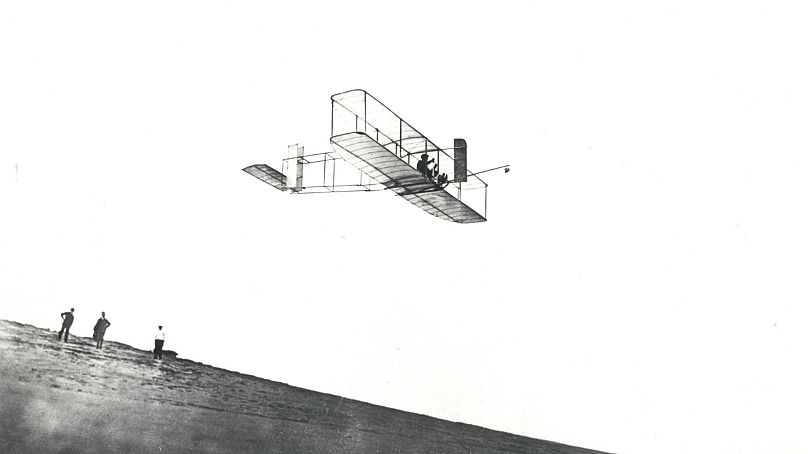

“What would have happened if there was an airline ready when the Wright brothers flew that first plane, who then took the engine on that plane said, ‘Well, this isn't efficient enough, so we can never do it’. And then the government said, ‘Well, we can't do it. So we're gonna ban flying’?” Finch asks.

“But it didn’t. It evolved and engines got better,” he says.

“10 to 15 years ago, no one dreamt of flying electric aeroplanes. People just said batteries weren’t good enough. But we’re now already seeing small planes make short journeys.”

Unkept promises

Ultimately, it will always come down to the commitments countries make towards a greener future. But in aviation, those public commitments have so far been lacking.

During the recent COP26, the International Aviation Climate Ambition Coalition (IACAC) was launched and signed by 17 countries.

Although much of the news surrounding the countries signing up to the IACAC said that this committed them to going net zero by 2050, Finch notes that’s not the whole truth.

“It didn't say that. In fact, it called on the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) to consider a long term net zero target and then a bit further down in the document it mentioned 2050 as a good year.”