A new study completed by the University of Edinburgh argues that the reason why we love and hate certain foods could be partly down to our genes

Olives, chilies, anchovies, tofu, sushi, liquorice, blue cheese, mushrooms and mayonnaise.

Are you a fan of all these foods? It would be very surprising if you were.

But why do people love certain foods and turn their noses up at others?

A new study reveals that the reason is not just to do with people's cultures or even their taste buds... Their genes play a significant role too.

What were the findings of the study?

Conducted by the University of Edinburgh and the Human Technopole research institute in Milan, the fascinating study has identified 401 unique genetic variants that influence which foods people like.

In the largest study of its kind, researchers collaborated with UK Biobank to gather data on more than 150,000 people's fondness for 139 specific types of food and drink.

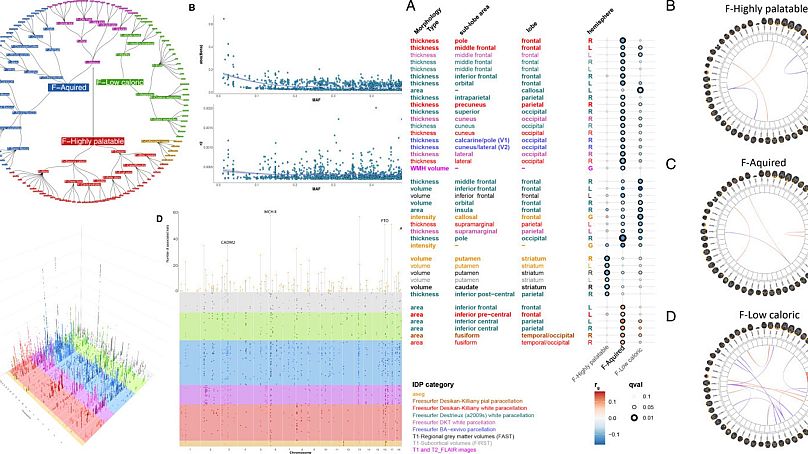

The team behind the study have developed a so-called ‘food map’ – showing how participants’ appreciation of groups of food and specific flavours are influenced by similar genetic variants.

The map reveals three main clusters of foods that share a similar genetic component.

"We mapped the foods to three main dimensions," explained Dr Nicola Pirastu, the Senior Manager of the Biostatistics Unit at Human Technopole. "The first is everything that's highly palatable - from meats, to desserts to French fries. Then we grouped anything that's thought of as healthy, like fresh fruit, vegetables and fish. Then there is another dimension which is everything you learn to like, such as coffee, spices and alcohol."

Researchers found that the three nutritional categories shared genes that are linked to several clear health traits.

For instance, the highly palatable foods are influenced by the same genetic variants also linked with obesity and lower levels of physical activity.

"Highly palatable foods also correlated with other not so healthy behaviours, such as not exercising and being sedentary. While people who instead liked all the healthy foods also liked exercising a lot," Dr Pirastu told Euronews Culture.

A higher liking for the more 'acquired foods' such as olives and coffee was linked to a greater likelihood of addictive behaviours such as smoking and drinking alcohol.

The study also completed MRI scans and found a correlation between the brain region responsible for processing pleasure and the genetic variation associated with extremely appetising and high calorie foods.

Whereas the other two food groups (low-calorie and acquired taste) were more closely correlated with the brain regions associated with decision making and memory.

What is the significance of these findings?

According to experts, a better understanding of what influences people's eating decisions could lead to the development of healthier and more personalised food products, improved nutritional treatments, and even the development of medicinal drugs to help extremely obese people lose weight.

"There is this big belief in the field that if you just expose children to some foods they'll just like it, just because you keep exposing them to it. And I think we show that this is not necessarily true," stated Dr Pirastu.

"If some people are genetically predisposed to not like broccoli, you won't be able to get them to eat it unless you understand why they don't like broccoli, and why broccoli is not good for them", he added.

"This is a great example of applying complex statistical methods to large genetic datasets in order to reveal new biology, in this case the underlying basis of what we like to eat and how that is structured hierarchically, from individual items up to large groups of foodstuffs," said Professor Jim Wilson, the Personal Chair of Human Genetics at the University of Edinburgh.

Check out the video above to hear the full interview with Dr Pirastu.