How climate change triggered a second exodus in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Ana used to live on the banks of the River Sava near Croatia, until the most destructive floods of the century turned her into a climate migrant.

“In 2014, when the floods came and ravaged the ground floor of our newly built house, we began to talk frequently about moving to Germany.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Ana (who did not want us to use her real name) and her son packed their belongings and, thanks to her Croatian passport, left the town of Domaljevac to join her husband in Frankfurt, where they have been living together ever since.

“Those events changed me profoundly,” she told Euronews. “I had always wanted to stay."

Ivana (also not her real name), a nurse at Domaljevac hospital, recalls others fleeing the floods: “A friend of mine was picked up on the first day of the floods by her husband, who came for her from Germany. She just got in the car and left, her house wasn’t even flooded. For her it was the trigger. She left and never came back.”

The North Pole, global warming and a real impact in Europe

The 2014 Balkan flooding has been directly linked to climate change.

“The globe is connected to a huge climate system, so big changes in some parts of the globe can lead to drastic consequences in another,” explains Vladimir Đurđević, a climatologist at the University of Belgrade. The warming of the North Pole, he says, triggers drastic changes in atmospheric circulation. Put simply, this means that rising temperatures in one location can affect wind patterns thousands of kilometres away.

In May 2014 a massive cyclone touched down in the Balkans. What was unusual was that it remained stationary. It sat over the region for too long, bringing relentless, heavy rainfall; in some areas, it rained for 21 consecutive days. The soil was completely saturated. This caused flash floods, erosion and landslides, which destroyed properties and livelihoods along small watercourses. The disastrous flooding along River Sava and its tributaries was described as “biblical” by Serbian newspapers.

The biggest rivers in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia all broke levees: the Bosna, the Vrbas, the Una and the Sava, the greatest tributary of Danube. The water did not subside for three days.

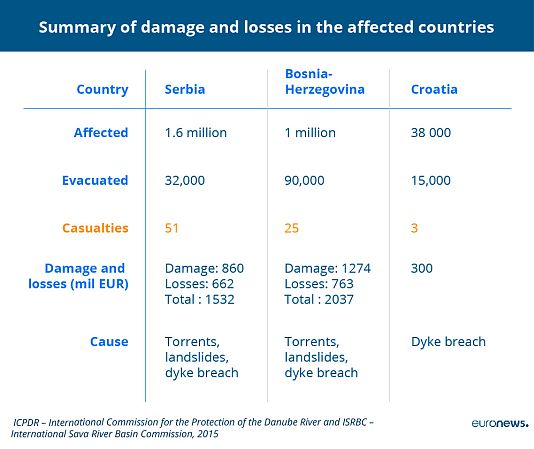

During the crisis, authorities feared damages could exceed those caused during the entire Balkan conflict fought between Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats between 1992 and 1995.

Depopulation: Europe's first international climate migrants?

The migration that followed is not simply a Bosnian story, but a European one.

In this part of the country, at the border with Croatia, there are entire villages that are majority Catholic Croat; driving around, however, it is not unusual to spot mosques or Serbian Orthodox churches. The Croatian passport, which is only available to Bosnian Croats, opens doors to the European Union but it is not a luxury that most Bosnians have. Following the floods, many of those lucky enough to have one, left to look for opportunities in countries such as Austria, Germany, Switzerland and Italy.

The floods may not have been the only factor pushing people to leave the country, but for many it was the tipping point.

“The floods were the final straw in our decision-making,” says Ana.

“This is a type of climate migration,” suggests Miroslav Lucić, deputy mayor of Domaljevac-Šamac, who confirms an increased outward trend after 2014. “In the '90s there was war-provoked emigration. Parts of our local community were basically annihilated. Then people came back and started living normally and moved on with their lives. Then the floods happened and took them five steps back. People did not have a sense of safety for their families while continuing to live here”.

Domaljevac, like many other villages in the small Posavska region, was almost completely submerged: 95.5 per cent of its houses were affected by floods.

In this area “the emigration began as soon as a natural disaster emergency was declared,” explains Tihomir Bijelić, editor and director of Radio Orašje, a local FM station. “Often, male members of the families were already working abroad: after the flooding, the rest of their family members followed suit."

Authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina have no way of measuring the number of people emigrating, but the World Bank estimates that the number of Bosnians living outside the country is nearly half the entire population.

In 2014, international news wires wrote that the disaster “triggered the worst exodus since the war”.

Ivo Marković, president of the municipality of Kopanice, estimates that 15-20 per cent of residents moved away. The local population now stands at 280.

For those who stayed, many did not receive any help from the state. Mara, a pensioner living in the village of Vidovice, right next to Kopanice, who has eight daughters all living abroad, says she “didn’t receive a single Mark”.

In Orašje, a bigger town just a few kilometres away, the town hall told Euronews that no statistical data existed but that “probably half of the working-age population had left. Floods had only been a trigger”.

A combination of its complicated political situation and location between richer neighbouring countries leaves Bosnia and Herzegovina in a difficult position when it comes to addressing its demographic crisis, writes Balkan Insight. Driving around the countryside, it is impossible not to notice the large number of empty houses, their shutters down.

‘I feel like a migrant in my own country’: Internally displaced people rebuild their lives

Up in the mountains of central and eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina, where communities are majority Bosnian Muslim, the same extreme weather events set off landslides that destroyed entire villages.

Small towns, such as Maglaj, faced reconstruction bills of up to €85 million. To put that into context, the municipality’s annual budget is just €4 million.

Displacement in these areas was mainly internal. These communities didn’t have the option of moving internationally, so they stayed put, or in some cases moved a few kilometres away, where they were relocated into purpose-built, functional but characterless towns.

“The financial support from authorities was very weak because they hadn’t planned for that. They never expected such a large-scale disaster. No authorities in Bosnia had much budget for that,” says Alen Ćosić, a local representative of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) mission.

Muhamed Jusufović, president of the municipal council of Žepče, which lost an entire neighbourhood in the village of Željezno Polje – today a ghost area of the town – told Euronews that the average annual income was between 4,000 and 5,000 BAM (€2,500), while the damage faced by residents “was between 50,000 and 100,000 BAM (€50,000)”.

One resident of this area admits he was only able to reconstruct his house thanks to “private donations from some wealthy people from Mostar”, in the south of the country.

Pensioner Šefik Čolić, 68, used to live uphill, in Žepče. After the mudslides, international donations made it possible for him to relocate downhill, in a newly built village on the banks of the Bosna river. He moved three times before finally settling down with his wife. “It is not how it used to be,” he says. “Me and my wife needed psychological assistance for quite a while."

In other areas of Bosnia and Herzegovina, such as Kalesija, reconstruction was only possible thanks to a joint effort from the Red Cross, the UN’s Organisation for Migration (IOM) and federal government funding, as well as donations from Bosnian families living abroad.

“Personally, I feel like a migrant because I had to move away from my own home… even though I stayed in my own country,” says Zekira Ikanović, whose house in Hrasno Gornje was destroyed by a landslide on 15 May, 2014.

She and her family were moved to military barracks for six months, then assigned to collective accommodation for two years before finally being able to build a new house in Memići – 40km away from her original home – thanks to donations.

Today she is unemployed. Her husband was a farmer but he had to take on new work doing occasional home repairs, a role that forces him to travel most of the time.

“We had taken a bank loan to build our previous house, but then the house got destroyed, and even then I had to keep paying back the loan until it was entirely paid off. They came searching for me,” Zekira says.

Unprepared and ill-equipped for large-scale disaster

“Before 2014, I had never heard of anyone having to move away for a natural disaster,” Zekira said. “I'm scared to even think about such a thing happening again."

Yet, the chance of another large-scale disaster hitting Bosnia and Herzegovina is far from remote.

“People put climate change at the bottom of their problem list. When authorities carry out reconstruction work, they just try to make things look the same as before, instead of preparing infrastructure to be resilient for future, stronger impacts,” warns climatologist Vladimir Đurđević. “We can expect to see more and more super-extreme weather events, leading to huge damage and to the suffering of people – with even more amplitude.”

“Rural areas are even more sensitive to climate change than cities and will not have the strength to recover when houses are blown away,” says Gianmaria Sannino, head of the Climate Modelling Laboratory and Impacts at ENEA.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the feeling is that people don’t have the means – financial or emotional – to face a similar disaster again.

“People here say they cannot stand another flood. I think young families could see it as a trigger to leave permanently,” says OSCE representative Ćosić.

“In terms of starting a new home or living in this country, when they weigh [up] the two options, they would rather opt for leaving Bosnia and [going] to Germany and starting a new job, a new life, rather than asking for a bank loan and getting themselves in debt for the next few years”.

This article was originally published in March 2020.