Salmon is one of the most popular fish eaten in Europe. Yet wild populations have been shrinking, and farmed salmon often comes with problems such as chemicals, sea lice infestations or overcrowding, leading NGOs and animal welfare organisations to call for changes to our eating habits.

Salmon is one of the most consumed fish in Europe, just behind tuna. Last year, the average European ate 2.39 kilograms of salmon, according to the 2025 EU Fish Market report.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Most of that salmon, however, doesn’t come from the wild. Although locally-concentrated efforts in some countries have more recently seen salmon return to rivers and streams, wild populations in Europe remain weakened by years of overfishing. This means that most of the salmon landing on our plates is imported from other countries: In 2024, 80% of salmon consumed in the EU was imported from Norway, followed by the UK, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, China and Chile.

And the vast majority of salmon we eat comes from fish farms. While this helps to avoid overfishing of wild populations, it can bring other problems with it. John Murphy, director of the NGO Salmon Watch Ireland, explained: “We have had a number of pollution incidents in regard to salmon farms. As you know, they're open cage technology, so, all the uneaten food, faeces and chemicals are released into the wider ocean environment.”

Apart from pollution, animal welfare is another main concern voiced by NGOs when it comes to these farms. Salmon farm cages are often overcrowded and may be affected by sea lice infestations. These parasites feed on salmon blood and skin. For free-swimming adult salmon, that’s not necessarily a problem, as they have enough space to survive normal levels of sea lice infestations. But in tightly packed farm cages, sea lice multiply rapidly and can kill large numbers of salmon, especially if the fish are young. Most of the time, sea lice infestations are treated with aggressive chemicals.

“What goes on in farms is all under the water. Nobody sees it. If the same practises were carried out on land, there would be uproar. There would really not be support to eat this product. But out of sight, under the water, certainly out of mind,” said John Murphy.

How can we identify sustainably farmed fish?

Not all farms, however, face these problems. Some also work with organic standards and make efforts to improve the welfare of the salmon.

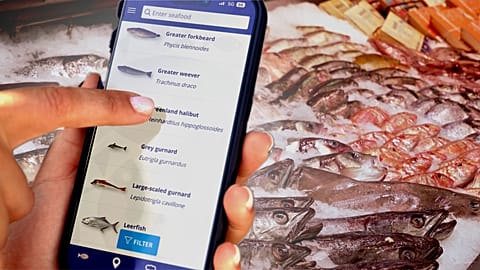

To identify more sustainably raised fish, consumers can look for labels like the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) label. This label is supposed to certify fish products that are “traceable” and have been farmed “with care”, according to the ASC website.

But this label and others may not always be a guarantee for sustainable farming, as some NGOs warn.

“Being ASC certified does not guarantee zero violations. Certification is based on audits, but it doesn’t prevent all forms of misreporting, non-compliance, or environmental impact,” explained Bruno Nicostrate, Senior Fisheries Policy Officer at Seas at Risk, an association of European environmental organisations seeking to protect seas and oceans.

“Large salmon firms that have been fined for escapes, seabed damage and overproduction continue to report ASC or other ‘sustainability’ certifications for significant harvest volumes. That’s because ASC certification is site-by-site. A company can be fined at one farm while other farms keep their certificates,” he said in an e-mail exchange with Euronews.

To find out what other NGOs say about these labels and what alternative products to salmon there are, watch our explainer video above.