The frozen behemoth has been drifting through the Antarctic since 2017.

In 2017, a giant piece of ice the size of a small country broke away from the Antarctic. Measuring 5,800 square kilometres, twice the size of Luxembourg, it was one of the largest icebergs ever recorded.

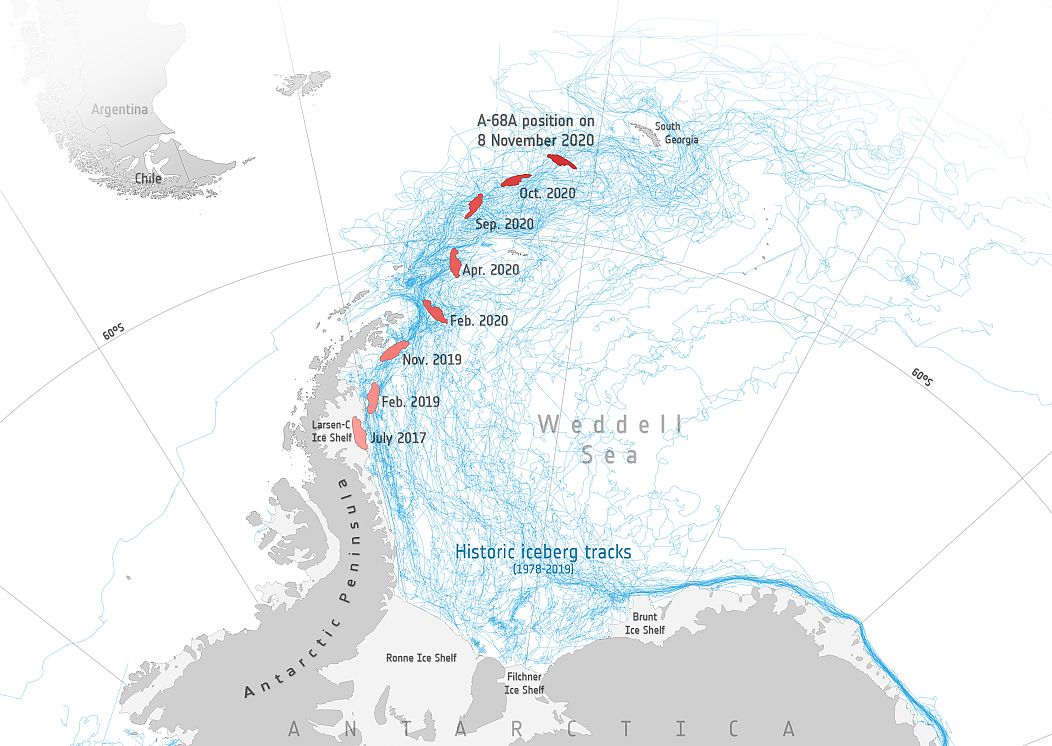

This vast mass of frozen water has been slowly drifting through the ocean since it made a break from the Larson C ice shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula three years ago. Tracked by satellites the berg, shaped like a hand with an outstretched index finger, began moving north in 2018.

That was until last year when the iceberg, labelled as A68, was quickly propelled into the Southern Atlantic by strong currents in the ocean.

During its travels, it has shrunk and broken in two, but its unpredictable nature is causing concern for conservationists. It is still so large that photographs captured by the UK Royal Air Force earlier this month couldn’t fit it into a single shot.

As the iceberg closed in on the wildlife haven of South Georgia in the southern Atlantic Ocean earlier this year, experts grew increasingly worried it could cause an environmental disaster.

“The iceberg is going to cause devastation to the sea floor by scouring the seabed communities of sponges, brittle stars, worms and sea-urchins, so decreasing biodiversity,” explains Professor Geraint Tarling, an ecologist at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

“These communities help store large amounts of carbon in their body tissue and surrounding sediment. Destruction by the iceberg will release this stored carbon back into the water and, potentially, the atmosphere, which would be a further negative impact.”

A threat to penguins and seals

South Georgia is one of the world’s most important ecosystems. The remote island is home to millions of macaroni, gentoo and king penguins as well as seals, albatross and other rare wildlife. Of the 30 species of birds that breed there, 11 are considered to be threatened or near threatened by the IUCN.

With no permanent human inhabitants, the island has levels of biodiversity comparable to the Galapagos Islands. To preserve this valuable ecosystem, the Government of South Georgia & the South Sandwich Islands created one of the world’s largest Marine Protected Areas in the region in 2012.

Despite the enormous iceberg starting to break apart in the last few days, it still poses a threat to the creatures that call South Georgia home. The largest of the separate pieces, labelled as A-68a, could still disrupt underwater ecosystems and stop animals from finding food.

This chunk is now heading south-east where scientists expect it will be picked up by a current that would carry it around towards the island’s east coast. Professor Tarling told the BBC that if the iceberg runs aground it would have “massive implications” for South Georgia’s animal inhabitants.

“When you're talking about penguins and seals during the period that's really crucial to them - during pup- and chick-rearing - the actual distance they have to travel to find food (fish and krill) really matters. If they have to do a big detour, it means they're not going to get back to their young in time to prevent them starving to death in the interim,” he said.

According to the European Space Agency, if the iceberg becomes lodged on the shoreline of the island, it could remain there for up to 10 years.

Studying the world’s largest iceberg

Ice shelves form as glaciers move towards the sea and sheets of frozen water float in the water. It takes thousands of years for them to build up and, as part of their natural lifecycle, pieces break off.

When these pieces split from Antarctic ice shelves, they almost always drift counterclockwise around the continent. If they survive long enough without breaking up, they are carried north towards South Georgia into an area known as “iceberg alley”.

The disintegration of the ice shelf is not thought to be directly related to climate change but as Antarctica gets warmer, experts predict events like this could become more common. That makes studying their impact on marine ecosystems vitally important and researchers hope to use this unique opportunity to do just that.

A team of scientists led by the BAS is setting sail next month on an urgent mission to study the iceberg. They will embark on a three-day voyage aboard an ocean research vessel called the RRS James Cook to research the impact of the giant piece of ice on the environment.

“We have a unique opportunity to visit the iceberg,” Says Oceanographer Dr Povl Abrahamsen who will be leading the mission. He explains that it usually takes years to plan for voyages like this but that governments recognising the urgency of the situation had allowed them to act quickly. “Everyone is pulling out all the stops to make this happen.”

Two submersible gliders will “fly” through the water collecting information about temperature, salinity, and levels of chlorophyll, a molecule vital for photosynthesis. The team will also measure the amount of plankton around the berg, a microorganism that generates half of the atmosphere’s oxygen and makes all ocean life possible.

“Whilst we are interested in the effects of A-68a’s new arrival at South Georgia, not all the impacts along its path are negative,” says Tarling.

“For example, when travelling through the open ocean, icebergs shed enormous quantities of mineral dust that will fertilise the ocean plankton around them, and this will benefit them and cascade up the food chain.”