In light of Iran’s internet blackout, Starlink has allowed some citizens to stay connected. How could its Direct to Cell service help mitigate future communications shutdowns and what role might the United States play?

During the wave of nationwide protests that rocked Iran in recent weeks, authorities severely restricted access to the outside world by imposing an internet blackout.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

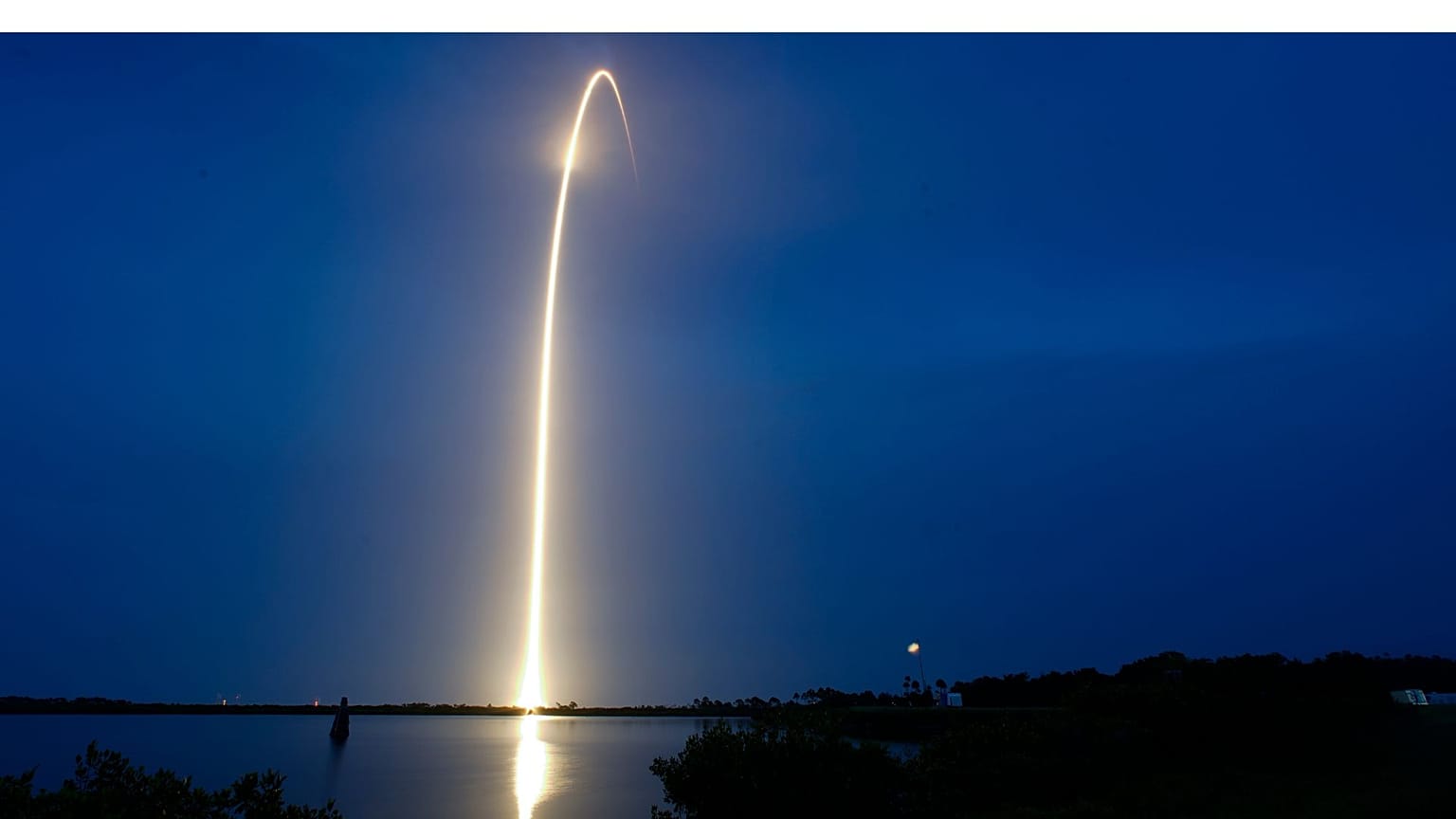

Despite this, some Iranians with access to Elon Musk's Starlink satellite internet service were able to send videos, images, and eyewitness reports to international media, albeit on a limited basis.

The use of Starlink in Iran, however, is illegal. The Islamic Republic has tried to disrupt Starlink's signal using electronic warfare systems, while security forces have patrolled and raided locations suspected of hosting the satellite receivers, according to reports.

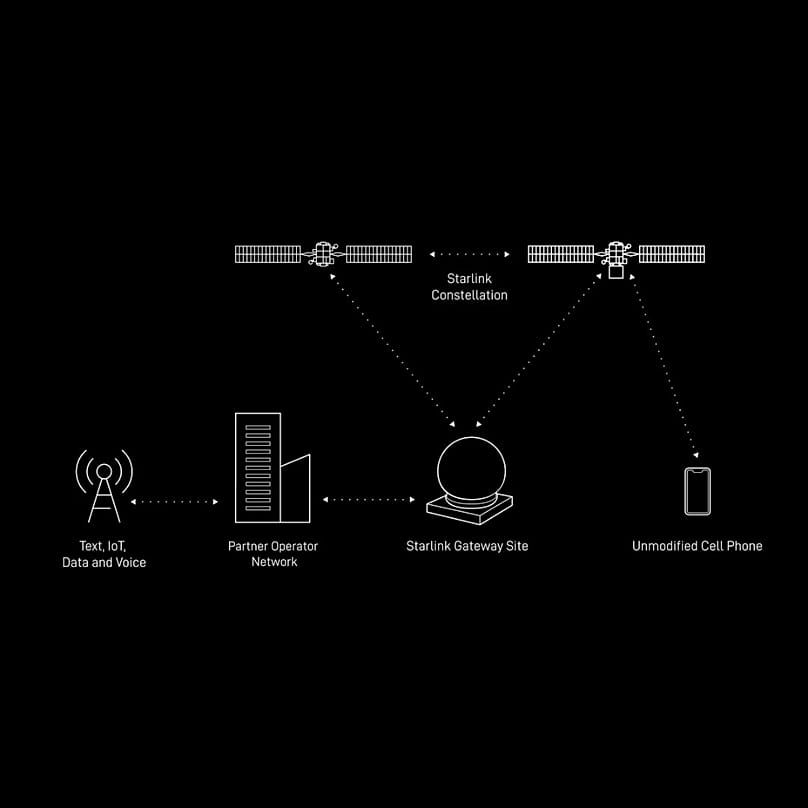

Starlink's recently introduced Direct to Cell (D2C) capability could make it harder for authorities to crack down on internet users, although it's not available in Iran. The technology aims to connect mobile phones directly to Starlink's satellite networks without the need for additional equipment such as the company's usual receivers.

To assess whether this technology could help mitigate prolonged internet shutdowns in nations like Iran, Euronews spoke to Mohammad Samizadeh Niko, assistant professor of electrical and electronic engineering at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

His research focuses on developing technical solutions to emerging information and communications challenges.

What is Starlink's Direct to Cell (D2C) service?

Direct to Cell is a new Starlink service in which satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) function like mobile phone towers in space. The system provides limited mobile connectivity directly to compatible smartphones, without requiring ground-based satellite terminals.

The service has entered early operational deployment in the US and New Zealand and is primarily designed to fill coverage gaps and blind spots in conventional cellular networks.

The key question, however, is whether such a system could technically compensate for large-scale and prolonged internet outages, such as those imposed in Iran.

Can existing phones use this service?

Satellites in low Earth orbit move extremely fast relative to the Earth's surface — much faster than ground vehicles or aircraft. This introduces several technical challenges.

A satellite is only "in view" of a user for a limited time, requiring frequent handovers between satellites to maintain connectivity. In addition, the high relative speed creates what is called the "Doppler effect", causing rapid frequency shifts that must be compensated for through advanced synchronization and tracking techniques.

The upside is that newer generations of smartphones are increasingly capable of handling these network conditions and supporting connectivity.

What are the technical limitations?

Smartphones are constrained by low transmission power and simple, omnidirectional antennas — unlike dedicated satellite terminals. To compensate for signal loss, D2C services typically operate at lower frequencies.

These limitations, combined with restricted bandwidth, currently confine D2C services to low-data applications such as text messaging.

What's more, D2C connectivity requires a clear line of sight between the phone and the satellite. Users must be outdoors or in open areas with an unobstructed view of the sky.

Could this service be used in Iran?

The system is unlikely to function well in densely crowded areas where many users attempt to connect simultaneously. Yet it could provide a minimal but key communication channel for individuals who otherwise have no access to the internet or mobile networks.

Only Starlink's high-speed satellite internet — which requires special hardware — has reportedly been made free for Iranian users. This service is distinct from D2C, which does not require hardware but is subject to different technical and regulatory constraints.

Is it possible for security forces to track users?

High-speed Starlink terminals can, in principle, be detected because they emit relatively strong microwave signals. These emissions can potentially be located using radar-based methods, although this is difficult due to the terminals' narrow beam patterns. Users are therefore advised to power the system only when actively in use.

By contrast, the risk of locating users via D2C connections is significantly lower, due to the system's reduced transmission power. However, Starlink itself would still have access to users' approximate geolocation data.

Can Starlink's services be disrupted?

There have been multiple reports of interference with Starlink’s high-speed service in Iran. While Starlink has improved its resilience through software updates, D2C services are inherently more vulnerable due to lower power levels and less efficient antennas.

In urban areas, high-powered jammers could disrupt D2C connectivity across distances spanning several kilometres. Nationwide disruption, however, would be far more difficult. Meanwhile, interference with GPS signals would not affect D2C functionality.

Why is Starlink's D2C service not operating in Iran?

Because Starlink is a US company and Iran is subject to sanctions by Washington, regulatory approval is required before D2C services can be provided in the country.

American firms must receive authorisation from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to transmit cellular signals into Iran. The US Treasury Department must also confirm that such services comply with sanctions regulations.

Iranian activists are reportedly lobbying the administration of US President Donald Trump to allow American companies to provide these services.

Nariman Gharib, a cybersecurity expert and activist, told ABC News that FCC licenses are issued for specific geographic regions and under defined regulatory conditions.

"The FCC has the authority to issue special temporary or emergency licenses if circumstances justify it," he said.

The US Treasury Department, Gharib added, must also determine if such authorisation would violate sanctions. Any delay in launching the service would be "entirely bureaucratic" and ultimately dependent on the political will of the US government.