The EU rejected the new draft deal, calling for stronger climate commitments and fossil fuel discussions

Delegates at UN climate talks worked into the early hours of Saturday to find common ground on a host of proposals, including a push by many nations to explicitly cite the cause of global warming: the burning of oil, gas and coal to power our world.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

With talks scheduled to wrap up on Friday, negotiators flew past that deadline, and it wasn't clear when they might finish as nations moved into high-level negotiations behind closed doors.

Brazil's new draft proposal deals with four difficult issues that include financial aid for vulnerable countries hardest hit by climate change and getting countries to toughen up their national plans to reduce Earth-warming emissions.

The EU has rejected the current draft, and any agreement still depends on reaching a consensus among the almost 200 participating nations.

Then there's the dispute over creating a detailed road map for the world to phase out the fossil fuels that are largely driving Earth's increasingly extreme weather.

Any such plan would expand on a single sentence — to “transition away” from fossil fuels — agreed upon two years ago at the climate talks in Dubai.

But no timetable or process was spelt out, and powerful oil-producing nations like Saudi Arabia and Russia oppose it.

EU rejects draft deal

More than 80 nations have called for stronger direction, and Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva also pushed for it earlier this month.

The EU rejected the draft deal and called for stronger climate commitments and fossil fuel discussions

Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra adamantly opposed the draft and threatened that EU negotiators would pull out of the talks if their demands for robust emission-cutting measures were not fulfilled.

The talks, which were supposed to conclude on Friday, have continued because of ongoing disputes. President André Corrêa do Lago of COP30 underlined the need of unity, saying that an agenda causing

The Brazilian proposals — also called texts — came on the heels of a fire on Thursday that briefly spread through pavilions of the conference known as COP30 on the edge of the Amazon.

No one was seriously hurt, but the fire meant that a day of work was largely lost.

Transition to greenhouse gas emissions irreversible

On phasing out fossil fuels, the proposal “acknowledges that the global transition towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development is irreversible and the trend of the future.”

The text “also acknowledges that the Paris Agreement is working and resolves to go further and faster,” referring to the 2015 climate talks that established the goal to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), compared to the mid-1800s.

A key issue is that the 119 national emissions-curbing plans submitted this year don't come close to limiting warming to 1.5 degrees.

Though the text didn't address a fossil fuel transition road map, it could eventually end in a vaguely worded section about a plan for the next couple of years in a separate road map.

The 36 nations that thought the text didn't go far enough included wealthy ones such as the United Kingdom, France and Germany, along with smaller climate-vulnerable islands Palau, Marshall Islands and Vanuatu.

Agreements at these talks are officially reached when no nation objects and typically require many rounds of negotiations.

In practice, the proceedings can end with agreements adopted and the presidency adjourning the meeting after noting any objections.

Instead of the usual small group meetings, the Brazilian presidency convened a meeting of nations' top officials behind closed doors for much of Friday.

It’s designed to lessen any nation's feeling left out of backroom deals, but it doesn’t let the public see countries’ objections.

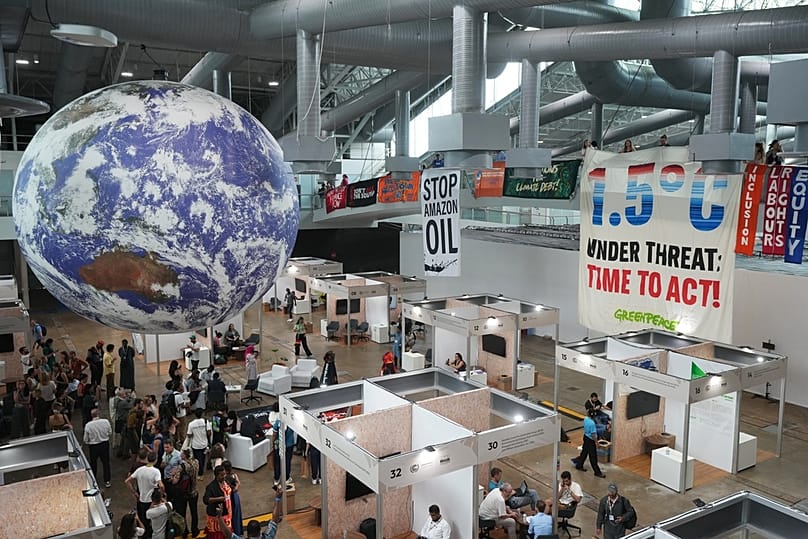

The annual talks this year are being held in Belem, a Brazilian city on the edge of the Amazon rainforest.