A fossilized pelvis found in Hungary suggests human ancestors were able to stand upright much earlier than anthropologists had realized.

Scientists have long thought that humans evolved from an ape that moved about on all fours like a chimpanzee, and they've puzzled over how and when our distant ancestors came to walk on two feet.

The fossilized pelvis of Rudapithecus, a long-extinct relative of humans and modern apes, may hold the answer. New research on the fragmentary remains suggests that when the beagle-sized ape descended from the trees, she didn't knuckle-walk like chimps or gorillas, as previously thought. Rather, she stood upright on two legs — much like a human.

"We've always asked, 'Why did our lineage evolve? Why did we stand up from all fours?' But Rudapithecus begs the question: 'Why did we never drop down on all fours in the first place?'" said Carol Ward, a professor of anatomy at the University of Missouri School of Medicine in Columbia, and lead author of a paper about the research published Sept. 17 in the Journal of Human Evolution.

"It causes us to approach the fossil record and our understanding of our origins in a fundamentally different way than we ever have before," she added. "It's a game-changer. The textbooks now get to be rewritten."

New look at old fossil

The 10-million-year-old pelvis was unearthed in Rudabánya, a city in northern Hungary, in 2006. It's the only known Rudapithecus pelvis, and one of only four reasonably complete ape pelvises more than 4 million years old.

"This is the oldest pelvis that looks like an ape pelvis," said study co-author David Begun, a professor of anthropology at the University of Toronto who discovered the fossil.

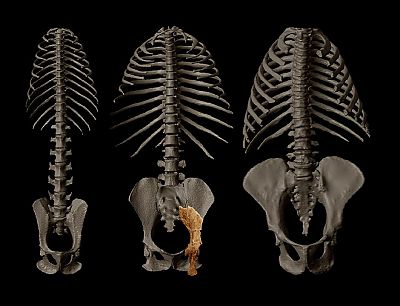

In 2009, Begun reached out to Ward, an expert on ape pelvis anatomy, for help in analyzing the bone fragment. Working alongside Mike Plavcan, a biological anthropologist at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, and Ashley Hammond, a paleoanthropologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, Ward and Begun spent a decade mapping the contours of the fossil and creating a detailed 3D computer model of a complete Rudapithecus pelvis.

They also created models of the skeletons of gorillas, macaques, orangutans and other modern-day primates. By comparing the models, they were able to infer Rudapithecus' anatomy — the curve of its spine, the position of its legs, the mechanics of its gait.

The research shows that Rudapithecus looks quite different from modern apes, whose short, stiff lower backs support their substantial weight while climbing trees but also necessitate moving about on all fours when on the ground.

Science

Rudapithecus looked more like humans, whose long, flexible lower backs make it easy to stand upright.

"If that's what our ancestors were like, then that transition to walking on two feet wasn't really that big a deal," Ward said. "We just specialized at doing it. We didn't have to have a fundamental change in how we moved."

Explaining bipedalism

Rudapithecus lived during the Miocene, a moderately warm period that ended between 8 million and 5 million years ago. Earth grew cooler and drier during this epoch, causing forests to shrink and forcing tree-bound apes to venture across broad expanses of grassland. If they were able to stand upright, Ward said, they might have fared better in the changing environment.

But does Rudapithecus' surprising anatomy really explain human evolution — and how we moved from four legs to two? Other scientists said more research is needed before firm conclusions can be drawn.

While Rudapithecus is clearly related to humans and modern apes, it's unclear whether it is the direct ancestor of any living species. It's possible that humans inherited upright posture from Rudapithecus or a closely related species, but it's also possible that Rudapithecus died off without passing on this trait.

"The study tells us something very interesting about Rudapithecus, and it tells us something very interesting about great ape evolution in general," said Jay Kelley, a research anthropologist at the Arizona State University Institute of Human Origins in Tempe, who was unaffiliated with the new study. "But [its long, flexible spine] could be something that is just peculiar to Rudapithecus."

Begun said researchers need to fill in the gaps in the fossil record between Rudapithecus and modern apes and humans to find the answer. Ward said the new study would inform that work, helping scientists to ask the right questions about how humans came to walk upright.

"Everybody has seen the drawing of the knuckle-walker that is slowly standing upright," Ward said. "That's what we always thought happened because all we had to look at was modern animals. But now, looking at the fossil record, we realize we have the wrong picture of what the ancestral animals would have been like. And this is a really big piece of the puzzle. "

Want more stories about science?

- An island imperiled: As their home melts, Greenlanders confront the fallout of climate change

- Are we living in a simulated universe? Here's what scientists say.

- A massive raft of volcanic rock could be heading toward Australia. That could be good news.

Sign up for the MACH newsletter and follow NBC News MACH on Twitter and Facebook and Instagram.