A controversial sculpture has divided opinion in Ireland, pitting rural traditionalists against the country's urban liberals.

A controversial sculpture has divided opinion in Ireland, pitting rural traditionalists against the country's urban liberals.

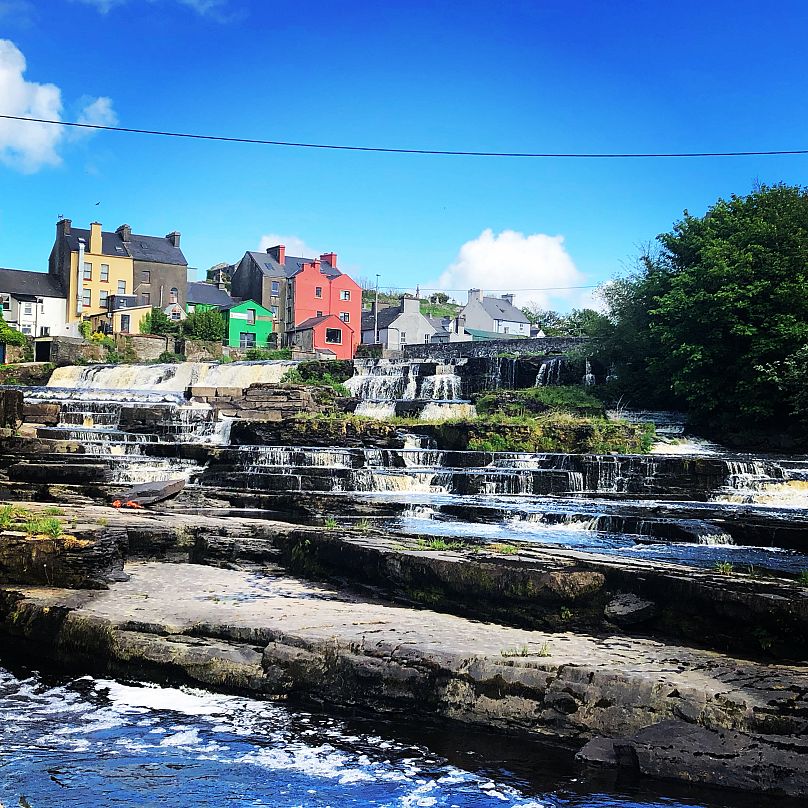

The furore is over a commission aimed to attract tourists to the small town of Ennistymon, on the west coast.

The sculpture is of a púca – the Irish word for spirit.

It is an Irish mythical creature, associated with the darker side of the country's folklore.

Locals say the sculpture is frightening and misrepresents the town’s heritage.

When the town priest condemned the púca from the pulpit, Irish people came out in their droves on social media in support of it, from MEPs to comedians - with even Hollywood star Chris O’Dowd throwing his two cents in.

The county council has now put the project on hold following objections from locals, though the sculptor is adamant it is relevant. A petition has been launched for its banishment and the issue is no closer to being resolved.

In a country that embraces technology and progress but still holds its traditions and mythology dear, the púca has divided opinion.

So, what's all the fuss about?

'They’ve come up with some paddywhackery'

In Ennistymon, local woman Jennie Corry doesn’t mince her words when she describes the púca as “grotesque".

"It’s not something you would throw in the middle of a residential area," she said. "It’s too strong an image.

“A lot of the people would be saying it’s not that they hate his [the artist's] work, it’s just not suitable where it’s going.”

Corry says a better place can be found for the púca “where he can be appreciated in the right setting. But not where we’re passing it day in day out, where he’s looking in someone’s bedroom window,” she says.

It seems to be less the fear of the púca’s dark side that’s at the crux of this debate. “Sinister” and “demonic” aside, some locals’ main objection is what they see as the inauthenticity of the proposed púca.

“We had horse fairs but we’re not particularly famous for it," continued Corry. "It’s a stretch. There is no story. It’s not folklore, it’s not a legend, there is no Púca of Ennistymon. It’s like they’ve come up with some paddywhackery, out-of-the-air story that’s not apt to the area. We don’t want a story invented.”

Locals have also been burned by what they see as a false view of their town due to a Twitter storm on the topic that broke out last week.

“The púca is creating a very bad image of the people of Ennistymon,” said Corry. “Famous people have been tweeting as if we’re all in Hicksville down here – like, ‘let’s fight this town, let’s get it on'.

"It has depicted us as religious fanatics led by the priest when that’s not what happened. I would hate for any artist to think that we’re led by the priest and we don’t like it cos it’s demonic.”

'We can just embrace the craic of having a big old mad statue'

But not everyone in Ennistymon is against the púca. Ger O’Donohoe owns the 'This is It' café in the centre of town and is a fan.

“I love it, it’s so beautiful and intricate. Sure, it’s a little creepy and dark, but aren’t we all?” he says.

The púca’s planned residence is right outside O’Donohoe’s café but the prospect doesn’t bother him greatly.

“I’m quite excited by it! I’d like to think we’ve moved on from having superstition and stories lead our decisions in Ireland.”

He has been hearing a lot about the púca over the past few weeks.

“The town is absolutely divided,” he says. “Personally, I’m a little disappointed with the reaction. There’s a very large artist community down here so I thought people would be all over it. I applaud whoever’s decision it was for going with something a bit mad. But I understand it too. Art is subjective. I, for one, can’t stand the Spire in Dublin and I signed a petition against that, I think it’s ridiculous.”

“With all we’ve learned and all we’ve been through, I think we can just embrace the craic of having a big old mad statue in the town, you know?”

'It's knocked me for six'

Kilkenny sculptor Aidan Harte, who studied classical sculpture at the Florence Academy of Art, was behind the artwork.

He said his half-horse, half-man sculpture aimed to tie in with Ennistymon’s horse fair.

“[The reaction] has knocked me for six. You think you know your country but that this happens in this day and age, it’s surprising. Everybody’s surprised. My contemporaries would be Irish sculptors, and the best you’d usually get is a small crowd when you cut the ribbon and that’s about it, but this - it’s like it’s touched a nerve,” he said.

So what exactly is a púca?

“He’s a type of fairy. He’s a mischievous rogue of a fairy, and depending on his mood he’s going to either give you good luck or bad luck. And he’s a shapeshifter, so he often appears in the form of a horse or a dog, or a pig or a cat. There are some descriptions of the púca as a wicked creature but then there’s as many that just described him as a bit of an auld scamp”.

Harte describes him as playing second fiddle to the leprechaun and the banshee, “but he’s back with a bang!”

The púca has appeared in literature from Shakespeare (the inspiration for Puck in Midsummer Night's Dream) to Flann O’Brien, and remains today in the origins of many Irish place names, such as Poulaphouca Reservoir.

Harte has long been interested in Irish folklore and especially the púca. With the cost of bronze being prohibitive on a large scale, Harte jumped at the chance to be able to make a two-metre model of his idol and bring his púca to life.

“The brief was to create something that you’d want to take your picture with, like Copenhagen’s mermaid or the bull at Wall Street. I think it was a clever and sort of bold idea by the county council. A nice but generic piece of modern art would be fine, but wouldn’t necessarily capture people’s imagination,” he said.

“The púca has captured imaginations perhaps a little bit too effectively.”

Harte says he didn’t set out to be controversial. “Maybe I’m naive. I knew he was an odd-looking fella, I was living with him in the studio for three months so I got to know him. I knew he’d make people look twice. This would be consistent with my work which is kind of intense and grotesque and strange.”

“But the funny thing is, people are talking about the púca like he’s real. I mean, to an extent he’s a real personality, and he’s a sculpture so I understand that he represents something of human nature. But people are speaking of it as if it’s as real as you and me.”

Harte says he understands those who are objecting.

“If they have an idea that something is being foisted on them, they’ve every right to speak up about it. I do hope that we can work it out.”

Harte agrees that there was no púca folk tale pertaining specifically to Ennistymon but doesn’t see why that should rule his púca out.

“It’s part of Irish culture generally. There are traditions of the púca all over Ireland.”

Ireland's got history when it comes to folklore

It might be hard to believe that a supernatural being could permeate public discourse to such an extent in 2021. But it’s not the first time that mythological creatures have influenced decisions in Ireland.

A motorway was re-routed in 1999 to make way for a fairy bush and farmers are often loathed to move the arrangements of stones known as fairy forts while farming, to avoid the wrath of the fairy folk.

Jonny Dillon is an archivist working at the National Folklore Collection at University College Dublin. He shares his love of folklore on his podcast, Bluiríní Béaloidis (Fragments of Folklore). He explains how mythology sits easily alongside modern society in Ireland.

“On the one hand you might ask someone outright if they believe in the fairies and they might laugh in your face but if you were to then ask them would they cut down a hawthorn tree on their land, or would they plough a fairy fort, they might grow a bit paler," he told Euronews. "There’s often a degree of passive belief in these things that isn’t really always at the surface.

“You can say on the one hand we’re all such rational, reasonable people nowadays but a lot of these beliefs and customs still linger”.

He refers to hundreds of accounts of the púca at the National Folklore Collection and says púcas were known all over the country and would abduct wayfarers who were out late at night.

“So they kind of took you up on their back and they galloped off over hedges and ditches, just racing off at breakneck speed and terrifying the person who was on their back,” he said.

Dillon says the stories had a moralising function, advising against being out late at night drinking or carousing or gambling.

“But with the púca, there is often an element of humour that you’d see in there as well – to entertain.”

Stories around the púca also served to frighten children.

“Parents would threaten him like the bogeyman. This was inherited and passed down over years.”

The púca would not have had its encounters in towns, says Dillon, but rather in remote areas of the countryside. “They wouldn’t go running down the main street, as it were. So the púca wouldn’t so much ‘get you’ outside the chipper as it would down in the fields and the forests!”

Every weekday, Uncovering Europe brings you a European story that goes beyond the headlines. Download the Euronews app to get a daily alert for this and other breaking news notifications. It's available on Apple and Android devices.