Venice exists in symbiosis with its surrounding brackish waters, and their health is also becoming increasingly fragile.

The city of Venice and its surrounding lagoon are irreversibly at the mercy of climate change.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Rising sea levels threaten to submerge the island in the coming decades, as the system of flood barriers currently keeping high tides at bay will become obsolete.

But this is only half the picture. Venice exists in symbiosis with its surrounding brackish waters, and their health is also becoming increasingly fragile.

New research has highlighted how warming seas are bringing invasive species that threaten the lagoon ecosystem and the livelihoods of local fishing communities.

Cannibalistic jelly invades the Venetian lagoon

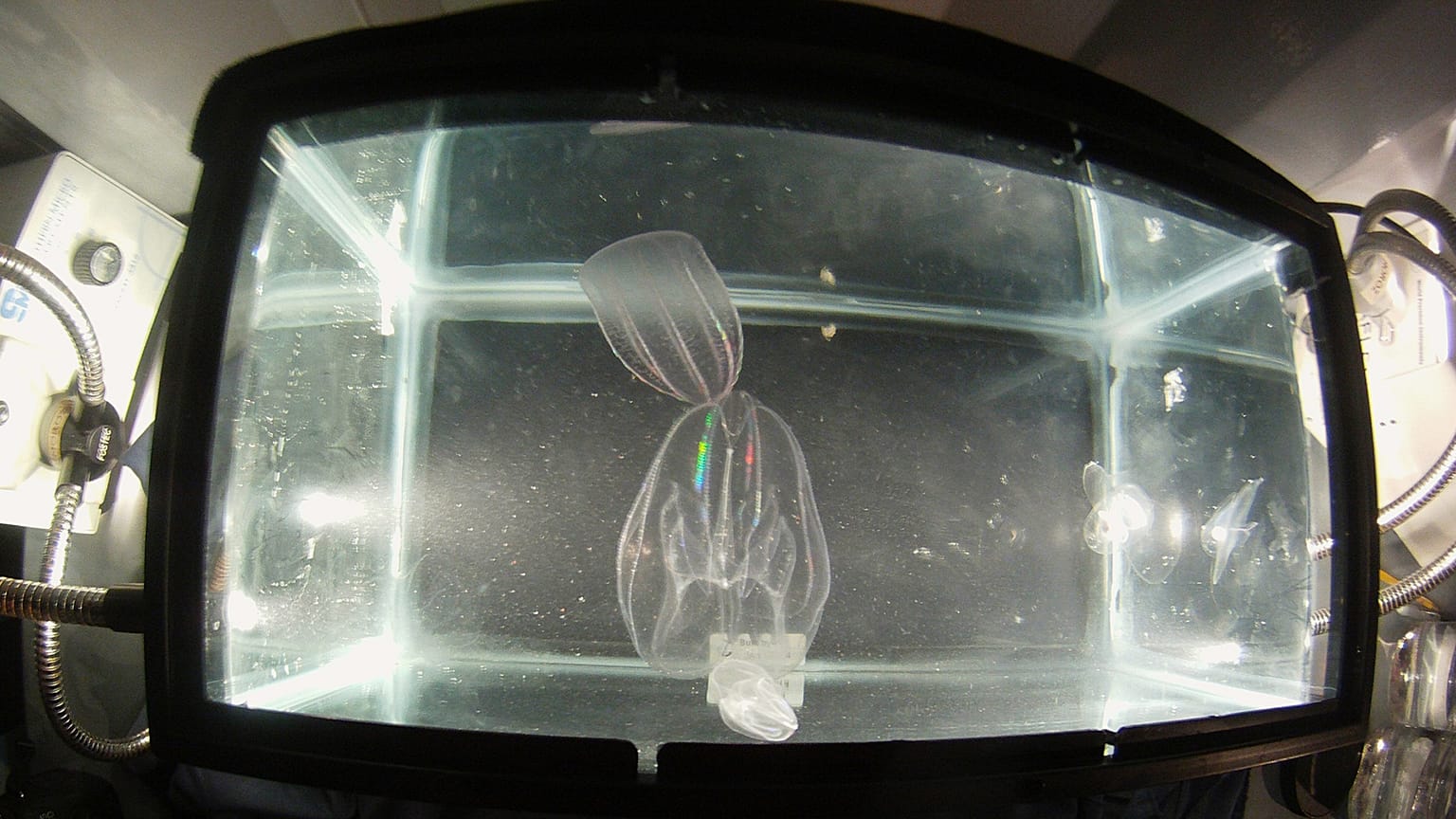

The latest rampant interloper in the Venetian lagoon is a cannibalistic comb jelly considered to be one of the 100 most harmful invasive species in the world.

The warty comb jelly is a ctenophora, a gelatinous invertebrate, and is known to consume its own offspring.

Also nicknamed a sea walnut, it has been present in the Adriatic Sea for almost a decade.

Recently, climate change has created particularly favourable conditions for the proliferation of the warty comb jelly in the waters around Venice, a new study by researchers from the University of Padua and the National Institute of Oceanography and Applied Geophysics (OGS) has found.

“This could increase its presence in large aggregations and, consequently, increase the risk of severe repercussions on the functioning of the entire lagoon ecosystem," says Valentina Tirelli, a researcher at OGS.

The study identifies a seasonal pattern marked by peaks in reproductive blooms in late spring and between late summer and early autumn. These blooms are likely influenced by elevations in temperature and optimal salinity levels.

The abundance of the species suggests that it is capable of surviving under a wide range of temperatures and salinities, though very high temperatures or low salinity can significantly impact its survival, the scientists say.

Invasive species threaten fishing communities

The warty comb jelly poses a significant threat to a thriving lagoon ecosystem in Venice.

“To support its high reproduction rate, this species is a voracious predator of zooplankton,” explains Tirelli, which is the essential diet of many fish.

“This ctenophore has also been shown to prey on eggs and larval stages of ecologically and economically important species, such as fish and bivalves, which may further compromise recruitment and ecosystem stability,” she says.

This poses significant challenges for fishing operators, who are seeing their catch depleted and their nets clogged by the slimy creatures.

“Our results show an overall reduction of over 40 per cent in catches of the main target species since the arrival of the invader,” Tirelli says. “The most affected species include cuttlefish and grass goby, both of which are culturally and economically important products for the Venetian lagoon.

In the 1990s, fishermen in the Black Sea blamed the collapse of fish stocks and its devastating economic consequences on the proliferation of the ctenophora.

Blue crabs decimate fishing catches in the Adriatic

Fishing communities in the northern Adriatic are already battling another fearsome predator.

The giant blue crab population has exploded in recent years. The crustacean is not indigenous to anywhere along Italy’s coastline. It likely made the journey over in the late 1940s from the shores of north and south America on cargo ships in the ballast water.

Though their presence is not new, the population of the fast-reproducing crab has surged to a critical point, especially as it has no natural predators in Italy’s waters.

The suspected culprit is climate change. “With warming waters, the crabs have become more active and voracious,” one fisherman tells Euronews Green. When the temperature of the water drops, the crabs eat and reproduce less, but recently the opposite has occurred.

“Usually, at certain times of the year, when the water drops below 10°C, this crab does not live well, but now finds the ideal temperature 12 months of the year,” Enrica Franchi, a marine biologist at the University of Siena, told AP news.

Blue crabs feast on local seafood and, with powerful claws that can rip through fishing nets, are seemingly unstoppable. Clams, mussels and oysters - as well as shellless crabs known as moeche in Venice - are all at risk.

Authorities and fishing lobbies are scrambling to find ways of using and disposing of the shellfish - including sending container loads to the US where it is considered a delicacy.

But Italian agricultural lobby Coldiretti has proposed adopting America’s eating habits and putting blue crabs on the menu.

Blue crabs are already appearing in fish markets and supermarkets at around €8-10 a kilo.

But the ‘if you can’t beat them, eat them’ plan comes with major risks. Dedicating resources to catching blue crabs as a food source undermines both fishing and culinary traditions in the Adriatic.

Skilled techniques of breeding, fishing and processing indigenous species like clams as well as recipes and dishes that are part of the area’s gastronomic heritage could be lost.