Christopher Schouten moved to the Basque country in the 90s to learn a new language. But in doing so, he became one with a whole new culture.

How is the identity of a culture transferred? For many cultures it’s through geography or heritage. But what if it was knowledge of a language that conferred a people’s identity.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Continuing our series looking at the minority languages of Europe, we’re looking at the Basque language, or Euskara.

Around 27 per cent of people in the Basque country use the language, with around 900,000 speakers.

An ancient language unlike any other

Spoken mostly in the Basque country located around the Pyrenees in southern France and northern Spain, Basque is a language isolate. That means the grammar and vocabulary don’t originate from a common language like French and Spanish do with Latin.

It’s thought to be the last remaining pre-Indo-European language in western Europe. It’s believed to originate from Aquitanian, and predates the spread of Latin throughout the region.

In fact, it has almost nothing in common with Latin, with a grammar that’s closer to Finnish or even Japanese, suggests Christopher Schouten.

Schouten grew up in Iowa but learned Spanish as a child. When he chose to study the language at university, he had the opportunity to travel to Spain as part of his studies.

A professor with an interest in the Basque region convinced him that he should apply to an exchange programme there. In 1990 he moved to the region for a year.

That year kickstarted a lifelong fascination with the language.

Basque’s resilience to survive millennia is particularly mysterious. Schouten’s theory lies in the region’s geography.

The Basque country spreads from the ocean up into the mountains of the Pyrenees.

“If the Basques ever had any conflict on the coast, they could just disappear inland into the mountains, and protect their culture and language that way,” Schouten suggests.

“The Basques in general, as a culture, just like many of the North versus South differences in many countries, tend to be a little bit more closed to external influence, a little bit more difficult to break into socially. I think that's probably the sort of stubbornness that's aided them over the centuries and maintaining their cultures and traditions,” he adds.

Defying censorship

That stubbornness has been particularly necessary through eras of active suppression of the language.

The use of Basque was heavily suppressed during the Franco dictatorship in the 20th century. Under Franco, it was illegal to teach the language and people were fined for speaking in it.

The suppression was eased after the 60s when a standard official Basque was established, but it’s still a big reason for a lack of speakers today.

While Franco did his best to extinguish the language, it has grown in the years since his fall. Schouten, who first visited in the 90s, has noticed a distinct increase in its use.

“I can see a continued renaissance of the language and how almost all the children are speaking it with each other now, and that didn't used to be the case,” he says.

One of the biggest hurdles to new learners is that it is a particularly difficult language to learn. For Spanish people who may be used to learning other Latin or Germanic languages, there are very few crutches to lean on in the learning process.

It’s why schools like Maizpide in Lazkao, where Schouten trained, offer adult education, but there’s still not a full takeup from the locals.

A unique national identity

The tragedy of locals not learning the language is the importance of the unique tongue to Basque identity.

Every nation or cultural identity is signified by something, Schouten says. “To be English, you have to have an English passport or have English parents. To be French you have to have French blood. To be Swiss, you have to be accepted by the community in which you live.”

But in Basque country, it’s all about the language. The ability to speak Basque is what makes you a member of the Basque culture, which is why Schouten felt such a warm reception when he came to the region.

Part of what makes the language unique is its use of grammatical case, especially the ergative case.

The word for a Basque person is “Euskaldun”, which literally translates to “one who has the Basque language”.

The word breaks down to “Euskal” which means “the Basque language”, “du” which is “have”, and “n” which means “person/thing”.

The language is an official language alongside Spanish in the Basque Autonomous Community as well as in Navarre. But it isn’t recognised as an official language in France.

The importance of the language to the culture also meant that after Franco more violence followed.

ETA, or Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (Basque Homeland and Liberty), was a paramilitary group which wanted independence for the Basque country. Formed in 1959, they committed terrorist attacks including bombings and assassinations.

In 2018, ETA officially disbanded, but there are still more than 260 imprisoned members of the group, mostly in Spain and France.

“I think the terrorism in the Basque Country, although ostensibly there to defend the language and the culture, among other political agendas they had, probably drove a lot of people away from the language, as well,” Schouten says.

“I had my own identity crisis with Basque in April of 1991, when about 20 metres away from me a car bomb that went off and killed a 17 year old girl.”

“I saw her die. And it really made me ask myself the question, ‘if this culture chooses to defend itself this way, is this something I'm really interested in?’ And I came to the conclusion that these weren't the defenders of the people, they were the enemies of the people,” he continues.

“The ceasefire that was declared was, I think, a pivotal moment of not only joy and peace, but also development of the culture that it can move ahead in peace,” Schouten says.

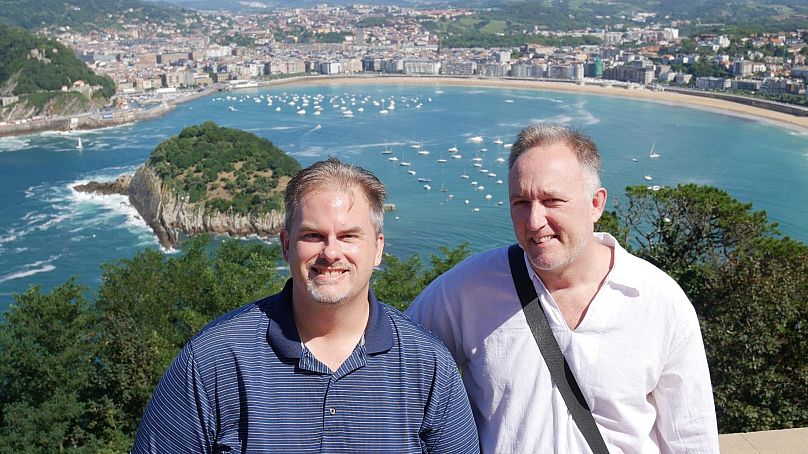

All of Schouten’s adoration for the Basque country, its culture and its language was reaffirmed when he returned last week. As an outsider who’s learned the language, he was celebrated and featured in local papers.

While Schouten has travelled the world and has a command of French, Spanish, Dutch and Japanese, it’s Basque that remains his greatest fixation. When he eventually retires, he intends to move to the region with his husband.

You can find our previous entry in the series on the Cornish language here.