Cornish is spoken by around 600 people in the UK. Although there's only a handful of people who still know it, it's history predates the English language.

What’s it like to speak a minority language?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

There are 79 minority languages recognised by The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. The charter covers many majority languages spoken in other countries, for example Polish speakers in Ukraine.

But it also covers some languages spoken by no more than a few hundred people.

In this series, Euronews Culture is going to hear from speakers of European minority languages to learn about their experiences.

Cornish

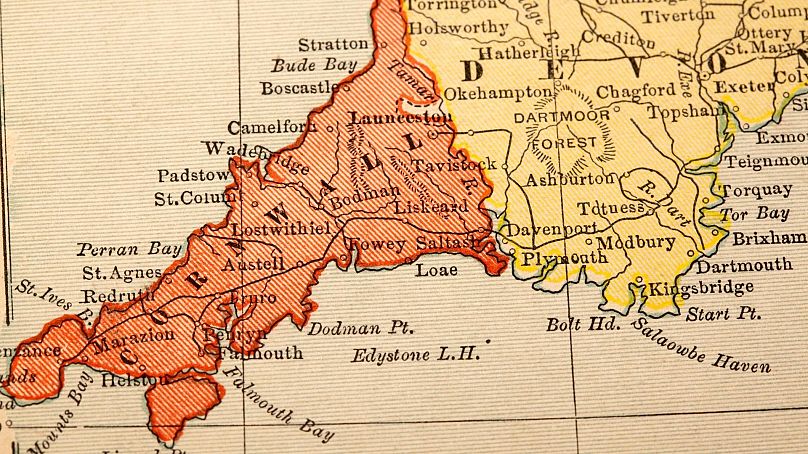

This week, it’s the Cornish language. A member of the Celtic language family, Cornish or Kernewek originates in Cornwall, at the southwestern tip of England.

A descendant of Common Brittonic - the language spoken in Britain before Roman rule or Saxon invasion - Cornish pre-dates English as a language of the British Isles.

Cornish was most popular between 1200 and 1600 AD, when nearly 40,000 people spoke it. It's also a sister language of Welsh and Breton and shares a lot of the same vocabulary.

The language almost became extinct in the 19th century, but was revived in the early 20th century.

The near extinction of the language is covered in Matthi ab Dewi’s book, ‘Like a Buried City’, which follows a family in the late 18th century who are dealing with the prospect of their language dying out.

“It was very much on the brink, in that the last people with traditional knowledge were just dying off as the revival began,” Matthi says.

While other minority languages like Welsh are represented by their own country in the UK, Cornwall’s lack of independence means its often been forgotten in language education legislation.

“Wales, as it is treated as a separate country from England, comes under separate governments and laws, which means that it has a Welsh Language Act," explains Matthi.

"In Cornwall, we are treated as part of England, which means that we don't have any Cornish Language Act, or any separate legislation to mean that we can acces funding to any degree, and support things like education, support for teachers, or support for broadcasting.”

According to a survey in 2011, there are around 600 Cornish speakers in the UK today, with 500 of them living in Cornwall.

Learning in Cornish

With so few speakers, it was somewhat difficult to find someone to speak to about the language. After reaching out, one person told me that many Cornish speakers were reluctant to be interviewed.

“We either get portrayed completely wrongly or have our time wasted and end up on the cutting room floor,” she explained.

“There’s been some good articles,” Matthi ab Dewi says. “But very often there’s a jokey aspect to it.”

Matthi grew up in Liskeard in Cornwall and he has a familial link to the area through his great grandmother and great aunts.

Although he didn’t grow up speaking Cornish, he was driven by an interest in his personal history, and decide to study the language at the City Literary Institute in Holborn, London.

While some schools in Cornwall are teaching the language, it’s still uncommon. The Go Cornish programme was created in 2021 to give primary school teachers the resources to start introducing young children to Cornish.

Matthi believes the best way to grow the language is for children to be immersed in it. That would mean learning it at school and speaking it at home.

Some kids cartoons like Peppa Pig have been translated into Cornish, but often it’s just one or two episodes which isn’t enough to provide an immersive experience.

It’s partly why Matthi started his Cornish language radio show. His weekly show is entirely in Cornish with music and interviews.

“The idea is that if you are fluent, it's something to have on for an hour,” Matthi explains.

“But I say to people to treat it like a normal radio, you don't actually listen to everything on the radio, it's on in the background. So you pick up on things.”

Growing a Cornish identity

Matthi wants as many people as possible to be able to appreciate and enjoy the language. And while more people are taking an interest, there’s still a shortage of fluent speakers to chat to.

“I can bump into people in my local town who speak Cornish, but I think there's still a level of people who aren't confident in their Cornish to be able to suddenly launch into something on any topic,” he says.

In Camborne, where Matthi lives, there’s a Cornish language shop that he likes to go to for a cup of tea and a chat.

“It's great to be able to take something so old into the modern age, and give it continued life. And when you go around Cornwall, you see all the Cornish language in place names and realise that you can understand what the hell they were talking about when they named the place.”

Matthi has fully embraced his Cornish identity, a strong identity which is separate from the majority English nationality. Born Matthew Clarke, he adopted a Cornish form of his first name while learning the language. He changed his surname to follow the Cornish patronymic tradition after his father died 10 years ago.

When asked why people should bother with a language that current estimates suggest only 500 to 600 people actually speak, he’s emphatic of its cultural importance.

“If there's one interesting building, which shouldn't be knocked down, you get a big campaign in the paper. Save this building! Put all the money into saving this piece of built heritage,” he says.

“But when it's oral heritage, or something which is intangible heritage, people seem to think intangible heritage is unimportant. If it's made out of bricks and stuff that you can drop it on your foot or run into it, then they think we'll save that.

"But the oral and the intangible culture is just as important, if not more important, so why not spend the same amount of money on building that up?”