After the four-day-long European Parliament election marathon that took place in 28 EU member states between 22-25 May (#EP2014), journalists, political analysts, and ordinary citizens have been predicting the potential composition of the next European Parliament and the next president of the European Commission. Today I will analyse an important aspect of these elections that worries me, but has not yet received enough public attention.

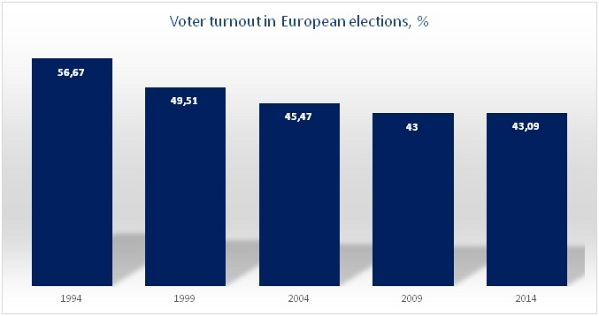

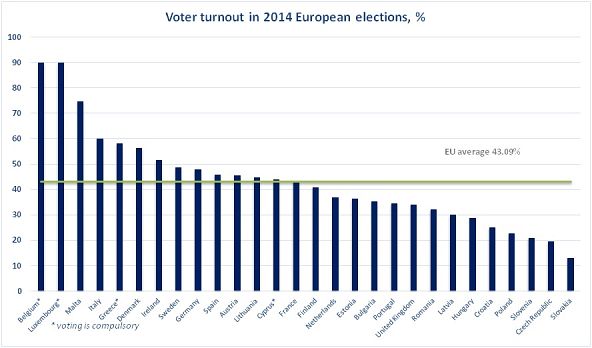

The first reactions suggest that the voter turnout of 43.09% (as opposed to to the earlier estimation – 43.11%) is an achievement for European democracy and civic participation in the EU. As EP spokesman Jaume Duch announced, “the long trend of falling participation in the vote has been reversed” (Figure 1). Whether this 0.09% increase is really a success for the EU needs to be confronted.

Figure 1.

Source: TNS/Scytl, European Parliament

Firstly, let us look at the participation rate in the EP2014 elections by country. Figure 2 shows that around half of the member states exceeded the EU average turnout, however, in four of these ‘above average’ countries voting is compulsory, so it is not really surprising that in Belgium and Luxembourg the turnout reached 90%. Still, considering voting is compulsory in Greece, only 3 out of 5 Greek citizens bothered voting, while Cypriots barely managed to surpass 43%, despite the same laws.

Figure 2.

Source: TNS/Scytl, European Parliament

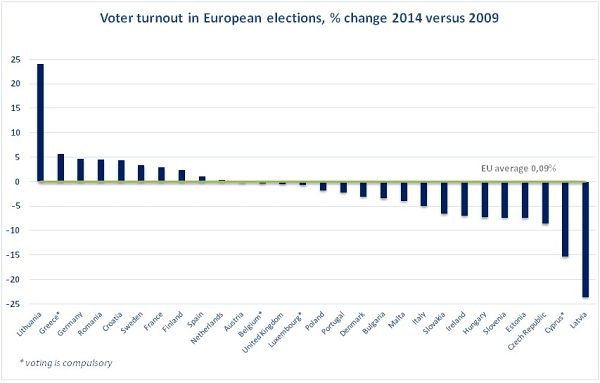

Comparatively good results in countries where voting is not compulsory were found in Malta, Italy, Denmark, Ireland – countries where the majority, i.e. more than 50% of eligible voters, cast their votes. However in Figure 3 we can see that in all four of these countries the voter turnout has actually fallen in comparison with the previous 2009 European elections. This implies that the EU has failed to close the democratic gap between the Union and its citizens.

Figure 3.

Source: TNS/Scytl, European Parliament

Overall, the EU average turnout has grown by only 0.09% compared to the 2009 elections (2013 in Croatia due to its recent accession). But it’s only in 10 EU member states that we see a rise in participation. The largest increase happened in Lithuania. Surely we can at least celebrate this huge 24% jump? Except… the European elections were held on the same day as national presidential elections, which, of course, attracted more public interest. A similar situation occurred in Greece and Germany where the European and local elections also coincided.

Further analysis of Figure 3 shows a dramatic difference in the recent turnout in Latvia. We could speculate that factors such as limited flexibility in voting rules (i.e. being registered at one particular polling station) and nice weather added to this decline. But undeniably the drop would have been smaller if local elections had not been held at the same time as European elections back in 2009.

In theory Estonia should be proud of its easy and accessible e-voting system that was launched 10 years ago. But unfortunately the system has been criticised for being unsecure and experts advised not to use it in the European elections. Despite the technical advancements there has been no improvement in voter numbers, with a below average 2014 turnout and a decrease of 7% from the previous 2009 elections.

Let’s briefly discuss the turnout in Austria – the only EU member state where, since 2007, the minimum age to vote has been 16. Several NGOs claim that allowing 16 and 17-year-olds to vote motivates them to exercise this right, and would raise overall participation. The data for particular age groups is not yet available but we can see already that turnout in Austria has actually fallen by 0.3%. Many await this data with a certain anxiety to see whether the new age rule has affected youth-interest in EU politics.

This year the European Commission itself tried to reverse the decreasing turnout by suggesting parties link their pre-election campaigns to the nomination of candidates for the European Commission presidency. By doing so, the Commission hoped “to better inform voters about the issues at stake in the [2014] European Parliament elections, encourage a Europe-wide debate and ultimately improve voter turnout.” I do not want to be pessimistic, but given the election results I have to admit that this innovation has barely affected voter turnout. And the EP2014 slogan “this time it’s different” has proven to be wrong. Instead, citizens across the EU have expressed their disillusionment with EU politics through abstention. And the small rise of 0.09% is only thanks to a good turnout in some member states where participation in elections is either compulsory, or where it happened to coincide with local elections.