First articulated in 1823, the Monroe Doctrine was largely meant to stave off European colonial influence in the western hemisphere, but modern presidents have used it to justify military intervention in Latin America.

Living former presidents of the United States do occasionally make it into the news agenda, usually thanks to past scandals, political endorsements or funerals. But what about someone who occupied the Oval Office in the early 19th century?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

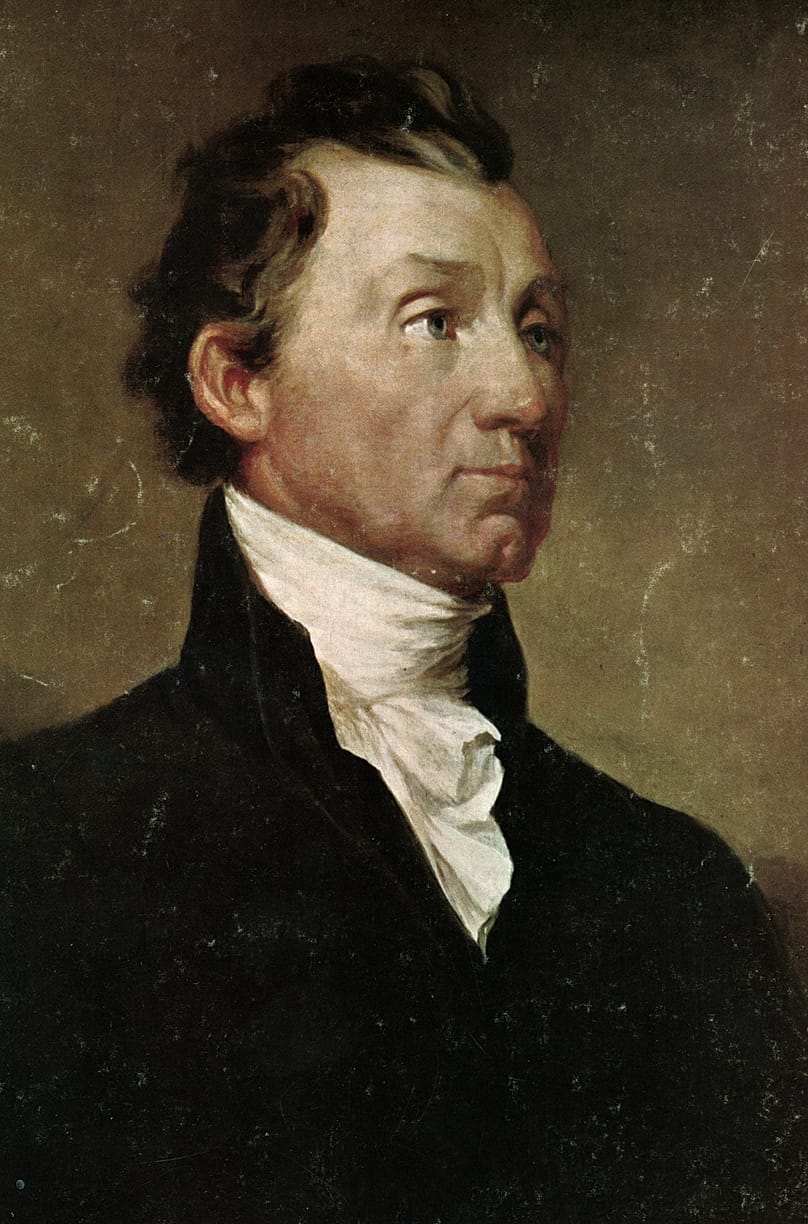

Suddenly the world is remembering James Monroe, the fifth US president, who was elected and re-elected in 1816 and 1820. His time in office was so prosperous for America that his contemporaries called it the “Era of Good Feelings”.

It was Donald Trump himself who invoked Monroe after last week’s US military operation in Venezuela, which resulted in the capture of the country's president, Nicolás Maduro.

Trump said the US would “run” the country during an unspecified transitional period, and described his approach as a modern update or reinterpretation of the “Monroe Doctrine”, which he jokingly referred to as “Donroe Doctrine”.

So, what is behind this policy that has everybody talking about?

As president, Monroe resolved long-standing grievances with the British and acquired Florida from Spain in 1819. But he is best known for asserting a national right of influence against European imperialism over the western hemisphere.

This idea, later dubbed the “Monroe Doctrine”, shaped the next century of international relations between the US and the rest of the world, providing a guiding principle for American presidents and policymakers who sought to make the country a global power.

In practical terms, the doctrine held that Washington would no longer tolerate colonisation, puppet monarchs or military intervention in the “internal” affairs of countries in the western hemisphere from the leading European imperial powers, namely Britain, France and Spain.

In return, the US would stay out of European conflicts and respect the remaining colonies in North America: Canada, Alaska and the various European possessions in the Caribbean.

Controlling the Americas

First outlined in a routine address to Congress in 1823, the Monroe Doctrine was conceived to meet the major concerns of the moment, but it soon became a watchword of US policy in the western hemisphere, and was used as a political and legal principle to justify numerous interventions in Latin America.

It was first invoked in 1865, when President Andrew Johnson exerted heavy diplomatic and military pressure to thwart efforts by French Emperor Napoleon III to establish a puppet monarchy in Mexico headed by Austrian Archduke Maximilian.

The episode ended in total success for Washington and disaster for Paris: the French troops withdrew and Maximilian was captured, later being controversially executed by firing squad.

In 1898, the Spanish-American War marked the true emergence of the US as a world power, bringing an end to Spain's colonial empire.

Fought under President William McKinley, the war also transformed the US's foreign policy from simply opposing European influence to actively asserting its own regional dominance and acquiring overseas territories like Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines.

Several years later, the European creditors of a number of Latin American countries threatened armed intervention to collect their debts. President Theodore Roosevelt promptly proclaimed the US's right to exercise "international police power" to curb such "chronic wrongdoing" in his so-called Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine.

Proving that Washington meant business, US Marines were sent to Santo Domingo in 1904, Nicaragua in 1911 and Haiti in 1915. Other Latin American nations viewed these interventions with misgiving, and relations between the “great Colossus of the North” and its southern neighbours remained strained for many years.

The Monroe Doctrine's anti-European tilt was essentially abandoned as policy principle in 1917 and 1941 when the US joined western democracies in their fight to win World Wars I and II in both Europe and the Pacific. But during the ensuing Cold War, the Monroe Doctrine experienced a comeback, with several US administrations invoking it to justify a series of interventions in the western hemisphere.

Most famously, President John F. Kennedy invoked the Monroe Doctrine during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, using the principle of opposing external interference in the Americas to justify confronting Soviet missile installations in Cuba.

Kennedy ordered a naval blockade of the island and issued a stark warning: any missile launched from Cuba would be seen as an attack by the Soviets on the US or its allies, and would be met with massive retaliation.

This was a crucial modern reiteration of the doctrine, shifting it from merely opposing European colonialism to countering the Soviet Union's attempts to wield influence in the Americas.

From Monroe to Reagan

In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan invoked the Monroe Doctrine to justify aggressive US intervention in Central America, particularly supporting anti-communist Contra rebels in Nicaragua against the leftist Sandinista government.

This policy, sometimes called the "Reagan Doctrine", aimed to roll back Soviet-backed influence in countries from El Salvador to Guatemala. Critics in the US and Latin America frequently denounced the approach as “imperialist”.

Another prominent modern invocation of the Monroe Doctrine prior to the Maduro capture was the US invasion of Panama in 1989, when President George H.W. Bush ordered US forces to remove military leader Manuel Noriega over allegations that he led a drug-running operation.

The US has levelled similar charges against Maduro, accusing him of running a "narco-state” and stealing American oil.

Maduro has denied those claims and said Washington was intent on taking control of his nation's oil reserves.

While various Latin American governments oppose Maduro and say he stole the 2024 vote, Trump's boasts about controlling Venezuela and exploiting its oil revive painful memories of past US interventions in Latin America that are generally opposed by governments and people in the region.

Whether Trump will prevail in the court of public opinion at home and in Latin America will largely depend on his actions toward Venezuela in the next weeks and months.

Trump also runs the risk of alienating some of his own supporters, who have backed his "America First" agenda and oppose foreign interventions Monroe Doctrine-style.

And they will have a voice: Congressional midterm elections are just ten months away.