The pandemic has already had a significant impact on the presidential primaries.

A deadly pandemic rages across the United States. Hospitals and clinics are overwhelmed, as new laws restrict movement and confine people to their homes. As the death toll surges, the government struggles to respond. Meanwhile, a national election looms.

Spanish Flu would ultimately kill 50 million people worldwide - including 675,000 Americans - between 1918 and 1919, sickening young and old, healthy and unhealthy. It wiped out entire families in an era where far less was known about diseases and how they spread.

On that level, it was a far deadlier disease than COVID-19, where fatalities have - so far - tended to be among the older generation and those with underlying health conditions. But despite the differences, the parallels between 1918 and what is happening in 2020 are stark.

Just as now, the U.S. in 1918 faced not only the spread of a deadly pandemic, but economic turmoil and a nation election which, by law, could only be postponed by a few weeks at most.

“I am literally watching my dissertation unfold in front of me,” said Kristin Watkins, a Colorado-based academic who wrote a 2015 paper on the Spanish Flu and its impact on the 1918 midterm elections in rural Nebraska.

“The disease is different, but [COVID-19] came into the US through the same ports, traveling the same way across the country. Hotbeds of infection were found, especially in east coast cities. Hospitals and clinics were overwhelmed, frontline medical professionals died in droves.”

Despite this, the elections of 1918 went ahead. Jason Marisam, a U.S. academic, believes the lack of debate about postponing the poll was “fervent civic pride engendered by the U.S.’s presence in WW1,” which America had entered a year earlier in 1917.

On election day in many states, voters wore face masks and queued in single file outside polling stations in what the San Francisco Chronicle referred to as “the first masked ballot ever known in the history of America,” Marisam wrote in his 2010 paper about the 1918 pandemic.

Pressures to postpone weren’t new a century ago

1918 wasn’t the first or the last time that America would press ahead with national elections despite significant external pressures to postpone or cancel them.

In 1812, Americans went to the polls in the seventh national election in the young nation’s history. Three months earlier, British forces had stormed Washington DC and burned several buildings, including the president’s mansion.

In 1864, with the American Civil War raging, turnout in the presidential election was a staggering 70% as voters elected Abraham Lincoln by a landslide. Meanwhile, in 1944, Franklin D. Roosevelt won a historic fourth term amidst the turmoil of World War Two.

In 1918, turnout was 40%, lower than the midterms four years earlier. Marisam points out that voting rates had been low for the first two decades of the 20th century, but calculates that the disease “was responsible for hundreds of thousands of people” not voting.

In an era, when U.S. elections have been decided on the basis not of thousands, but of hundreds of votes (in 2000, George W. Bush won Florida and ultimately the presidency with a margin of 537 votes), the effect of COVID-19 has the potential to be significant.

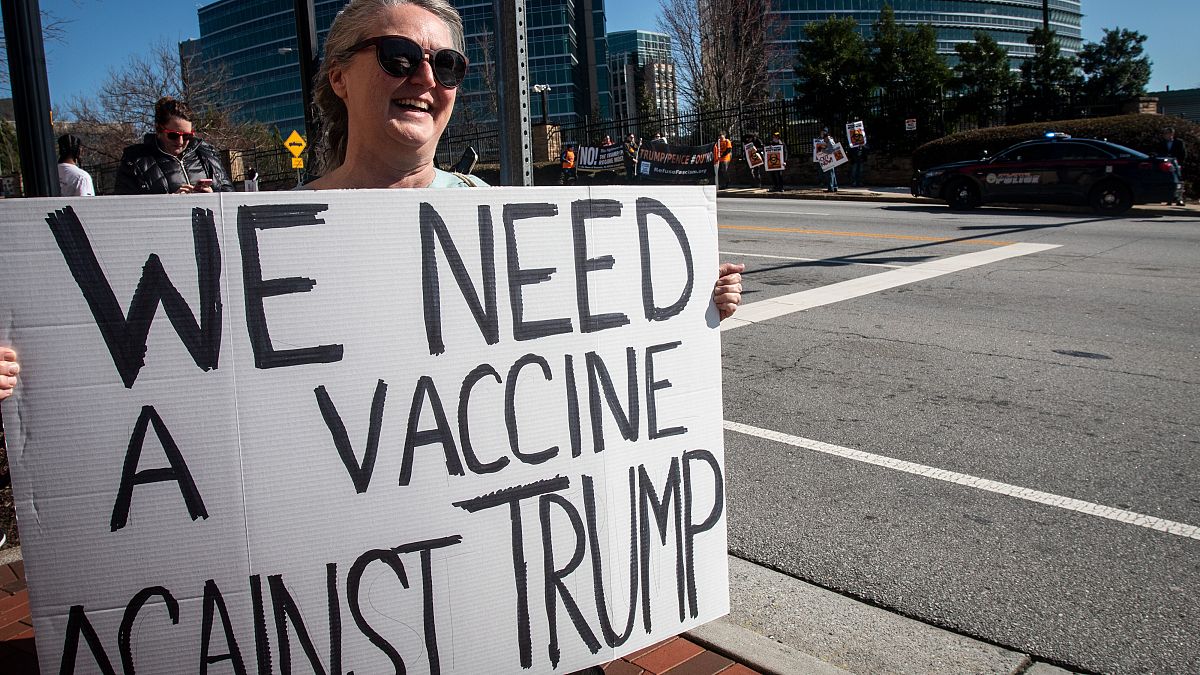

The virus has already led to the postponement of close to a dozen Democratic primaries, leaving the frontrunner, former vice-president Joe Biden, in limbo. Despite Biden’s clear lead, rival Bernie Sanders has yet to drop out of the race, meaning the party does not yet have an official candidate to take on President Donald Trump in November.

Both Biden and Sanders have resorted to video addresses from their homes in Delaware and Vermont respectively, while AP reported this week that the inability to hold fundraising events has left the Biden campaign critically short of cash to take on Trump in less than eight months.

But those political concerns are nothing compared to the impact on the actual election in November if the spread of COVID-19 cannot be halted.

The Constitution will have final say

Congress does have the power to postpone an election, but the U.S. Constitution mandates that the president can only serve for four years, and on January 20, 2021 - Inauguration Day - either Trump or his rival will be sworn into the Oval Office.

Todd L. Belt, director of the political management program at George Washington University, told Euronews that even though the election could be delayed, it is unlikely to be.

“Elections are an important symbol of national unity and endurance, so I don't think they will be cancelled or postponed,” said Belt.

Absentee voting is key

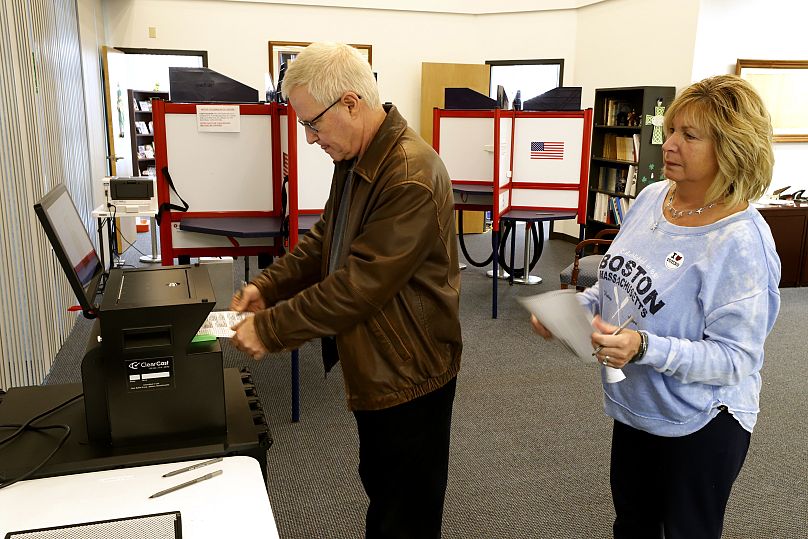

Several measures have been suggested in recent weeks to prevent millions of Americans turning up at polling stations in November and infecting their friends, neighbours and election workers, not least a rapid expansion of absentee ballots and voting by mail.

Belt pointed out that in 16 U.S. states, absentee voting already makes up more than 50% of the electorate, while in 2016 voting by mail made up 41% of all votes cast.

“A switch to all-mail balloting could be possible. The only question would be ramping up to the scale needed for all voters. These decisions are made by the states themselves,” he said.

Michael McDonald, a professor at the University of Florida who tracks voting issues, told AP this week that as well as being safer, voting by mail is also cheaper than voters casting ballots in person. McDonald added that because older voters tended to vote by mail, the shift to an all-mail ballot could favour the Republicans, as Democrats tended to vote in person.

But while voting by mail prevents voters turning up in droves to the same location amid a pandemic, it is not without risks. Votes have to be opened, logged and counted by individuals in a shared location, risking mass infections of election workers across the country.

As it stands, a poll from the Pew Research Center in late March found that about two-thirds of Americans would be uncomfortable voting at polling places during the outbreak. With the expectation, then, of low turnout in 2020: Is it Trump or the Democratic candidate who is set to gain?

“The conventional wisdom is that higher turnout favours Democrats, since a greater proportion of low-propensity voters are poor and working class,” said Belt.

“However, nonvoters' preferences fluctuate dramatically and are different from state to state, so therefore very difficult to predict.”

The difficulty in making that call is compounded by the fact that Trump voters are not traditional Republican voters, while many traditional Republican voters might opt to vote Democrat. Older voters, who tend to vote Republican, are more at risk from the virus and less likely to turnout.

Politics aside, if COVID-19 is still spreading in November, 1918 has lessons for the potential impact of holding a national election during a pandemic.

“It is anecdotal,” said Watkins, “but yes: infections rose significantly after the quarantine was lifted for elections.”