The Rosetta comet hunting mission has spotted its prey, and is now moving swiftly towards its target. The ESA space mission, which spent much of the last decade in hibernation, is now fully awake and approaching comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko as it flies into the inner solar system.

The distance between the two is now less than five million kilometres, close enough for the OSIRIS instrument on board Rosetta to be able to image the comet against the backdrop of stars.

Rosetta is currently approaching at high relative speed, but it will begin to slow down and adjust its course this May and then eventually move into a kind of triangular orbital pattern around the comet during the first week of August, at a relative distance as low as 100 kilometres. So, the coming months are set to be some of the most exciting in modern space science, as a spacecraft begins to approach and then fly alongside a comet for the first time in history.

Where is Rosetta now?

ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft operations manager Sylvain Lodiot gives an update on the mission.

What will it look like?

One of the key questions that everyone wants to see answered is: What will the comet look like?

We already know that most comets have the basic form of a lumpy potato, and that they are mostly made up of ice with a good smattering of dust. What’s more, comet 67P has been photographed from a distance, meaning the scientific visualization graphics circulating in the media do have a solid basis in reality.

But scientists really don’t know what the surface of the comet will be like. Will it be full of ravines and peaks, will it have a smooth, dirty surface like an old snowdrift; will jets of gas and ice fly from all over the comet, or just certain areas?

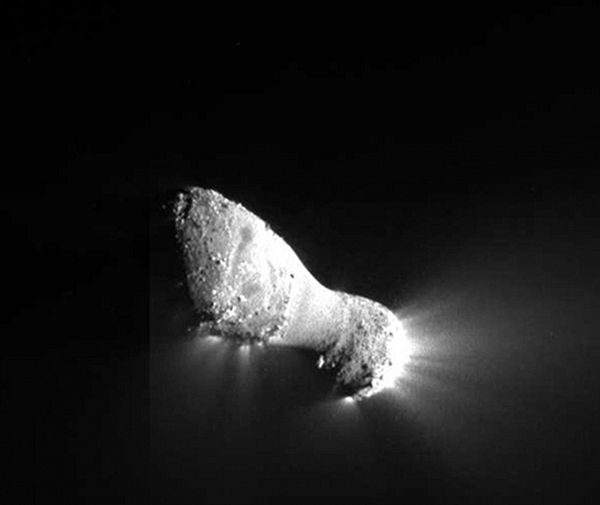

We have photographed other comets from a close distance in the past – ESA’s Giotto mission famously took photos of Halley’s Comet as it flew through its tail in 1986, and over the past decade NASA’s Deep Impact and Stardust missions have taken pictures of comets Tempel-1 and Hartley-2.

Where to land?

However we don’t know to what extent comet 67P will be similar to those ‘dirty snowballs’. And it’s important to know, because we’re looking at this comet with the eyes of space pilots, as the Rosetta team is going to try to land on the surface.

Rosetta will set about imaging and mapping the four-kilometre wide comet as soon as it arrives alongside, doing its best to create an accurate image of this otherworldly object, and to recce a shortlist of landing sites for the Philae probe that sits nestled inside the spacecraft.

Philae doesn’t have to do anything other than sit back and watch for the time being. Its moment will come when the summer in the Europe is passed and we enter the month of November, when it should, in theory, push off from Rosetta and land on the comet, screwing itself into the ice and hitching a ride on an object the size of an Alpine mountain.

The Philae lander has its work cut out once on the comet surface, as it has an initial 64-hour battery life in which to take high-resolution pictures of the comet and to drill over 20 centimeters down into the surface and then analyze the chemical composition of what it finds.

This is Rosetta’s first sighting this year of the target comet:

What will we find on the comet?

If the Rosetta mission manages to do what it set out to achieve- to fly alongside a comet for many months, and put a lander on its surface – it will be an extraordinary technical achievement. The engineers who made it happen will receive very deserved praise for having pulled off such an unprecedented flight, which some describe as the greatest challenge in space since the Moon landings.

Nevertheless, longer-term, the science of Rosetta promises real breakthroughs in knowledge – not only about comets and the formation of our solar system, but also ultimately where we came from too.

Simply put, Earth wouldn’t be the same if it wasn’t for comets. For one thing, it’s believed that early in our history comets brought water – perhaps most of the water that we see around us – to a hot, young Earth. Secondly, the NASA Stardust mission brought back a sample of comet dust to Earth and found that it contained glycine, an amino acid and a fundamental building block of life.

So, while we can’t expect Rosetta to find little bugs on 67P, we should expect the mission to find some of the little compounds that could be used make up the little cells that could be used to make up some of the little bugs, and that’s terrifically exciting for anyone researching life, the universe and just about everything.

We’re following the Rosetta team as they chase down a comet in our monthly one-minute series Comet Hunters. It offers a unique backstage view of the mission and highlights the real-life experiences of the men and women who are making the mission happen.

Links:

The Rosetta

- Artist’s Impression of 67P

Artist’s Impression of 67P

- Comet Halley nucleus as seen by Giotto

ESA

- NASA IMAGE

NASA

- Image of comet Borrelly

NASA