Wine brought by Ancient Greeks, the Death of Grenache, and how a natural phenomenon creates the perfect conditions for organic and even biodynamic vineyards. Euronews also finds out what it's like to make wine while Colonel Gaddafi is running the country...

The Rhone Valley. The place where Caesar's men first made wine in France. The site of the Anti-Pope during the 14th century. Here you don't just have an important river, you have a vital wind as well.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The Mistral might well be the reason that organic and biodynamic wines thrive in this region of Southern France. Its name comes from the old French dialect of Occitain, and means 'masterly'. Its cold, often violent stream blows through Provence and into the Mediterranean. With the Mistral in their armoury, a winemaker won't need to worry too much about pests or rot. Nature will protect the vines. And it has done so since Ancient Greeks brought the essential vitis vinifera vines from Asia Minor to what became Marseille. By the 1st Century CE, the Romans had conquered and viticulture had firmly taken root, and the Rhone opened up trade with the rest of Europe.

First, let's get the bank issue tidied up. There's a left and a right bank to the Rhone. And if you're anything like me you will picture a map and assume the left bank is the one on the left as you look at a typical cartographic rendering of France, with Paris to the North and Marseille to the south. But no. Awkwardly, that's the right bank. Turn your mental map upside down and remember your left and right as if you were the Mistral, blowing your chilly might towards the Med.

The Rhone actually begins in Switzerland. A glacier (cunningly known as the Rhone Glacier) in the canton of Valais is its source. It flows west through myriad vineyards, many of which grow the national grape, Chasselas, through Sierre and Sion towards the Vaud region and Lake Geneva, where I first met it and had never seen a river quite so blue. From thence to Lyon where it makes a sharp dogleg to the south and stays on that bearing until it meets the sea.

I have decided to make my starting point Avignon, in the southern Rhone. It's the perfect place to stay if you want vibrancy, atmosphere, and the plethora of city perks while remaining within a short drive of the major crus.

We should have a word about these crus.

The stratification of Rhone wines

There are often divisions, in the traditional footballing sense, when it comes to wine in many regions of Europe. Much like with Burgundy (or Bourgogne as we should now say) and its Grand Cru, Premier Cru, Villages and Regional indicators; so, too, the Rhone. That doesn't mean to say, of course, that your palate will prefer a wine from the highest quality bracket. Indeed, it's feasible that Manchester United could lose to Crewe (not Grand Crewe, naturally) Alexandra. But perhaps not very often.

Wine classifications are a fairly solid barometer where quality is concerned, but should not be thought of as the be-all and the end-all here. If winemakers don't play by certain rules, they cannot sell their wines with certain classifications on the label. And sometimes, winemakers can be mavericks and make their own rules. Renegade wines of this ilk can be as extraordinary as anything heralded by traditional systems of stratification. Bottom line - it's all worth a try.

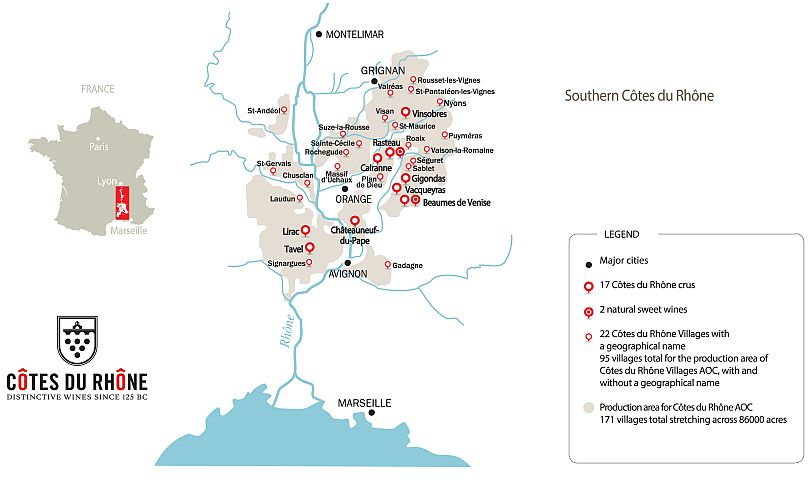

In this warm land of sunshine and lavender, there are sixteen top-level wine appellations known as crus. Half of them are in the northern Rhone and include the famous names Cote Rotie and Hermitage. But here in the south, there are also eight including Gigondas (of which much more later), Vacqueyras and perhaps the most historically lauded of them all, Chateauneuf-du-Pape. The latter is independent of the rest of the Rhone Valley wine regions and has its own PR machine, workforce and identity. I tried not to mention it too much in the areas I visited and didn't dare ask if they play the occasional football match on Christmas Day. Cru rules involve specifications for hand-harvesting, maturation and grape selection. But the last one of these isn't actually as strict as lower classifications. Château de Beaucastel, for example, famously uses a melange of 13 grapes in its flagship wine.

Next down the pecking order are the Cotes-du-Rhone Villages appellations. 95 communes across the region make Villages wines. And if you are hardcore enough to reduce your yield (how much wine your grapes actually produce) to a specific level (up to a maximum of 40 hectolitres per hectare) you can put the name of your commune on the label. Only 18 communes currently do this.

The third level is the one that represents most of the Rhone's winemakers. AOC Cotes-du-Rhone. 171 communes make this standard of wine. That's over four thousand 'vignerons'. And don't go thinking there are no rules here. You can't have a higher yield than 51 hectolitres per hectare.

Yet, more. After these wines, there are countless Vins de Pays and Vins de Table. The Rhone is enormous. You would have to go to Bordeaux to find a region with a greater winemaking area and volume.

Now, why would anyone put a picture of a spaceship in a wine article?

Although it is true that wine has been in space, it still seems incongruous, doesn't it?

But here's a FUN FACT from the Cold War era, when there was a significant amount of paranoia...and a mayor astute enough to know how to cash in on it.

A law was passed in Chateauneuf de Pape in October 1954 that prohibits incursion by alien spacecraft anywhere on the territory.

Article 1 - the flight, landing and take-off of aircraft known as "flying saucers" or "flying cigars" of any nationality are prohibited on the territory of the municipality of Chateauneuf du Pape.

Article 2 - any so-called "flying saucer" or "flying cigar" aircraft landing on the territory of the municipality will be immediately impounded.

The Grapes

Blends are more common than single varietals in the Southern Rhone but there is one grape that unquestionably claims pride of place in this region. Grenache Noir.

This grape has comparatively thin skin but makes wine that is usually high in alcohol and low in acid. Thus it can pack a punch while still remaining smooth. A wine just made from Grenache might be quite pale due to its thin skin, and thus make you think it's not going to be very bold or strong. Watch out for that. It tastes a lot more like it looks. The vines are planted in a style called 'gobelet' (they stand alone), and resemble ancient, truncated trees with, perhaps, the faintest suspicion of evil.

You will find a lot of this kind of grape but known under its Spanish name, Garnacha, in Rioja wines as part of a blend with Tempranillo. But here in the Rhone it's often the foundation stone for full-bodied, textured wines in a blend with Syrah (the darling of the Northern Rhone) and another grape called Mourvedre. The latter grape is much deeper in colour and gives these blends, often referred to as GSM blends, a darker hue and a lot more acid and tannin. Grenache will give you plenty of pepper and maybe a bit of leather on the nose.

There are quite a few red grape varietals but those are the main three, and there's a similar deal with the whites. The Southern Rhone is not, yet, renowned for its white wines but you'd be a boob to ignore them.

On the right here are bunches of Grenache Blanc, which alongside Marsanne, Rousanne and Clairette, make up the lion's share of Southern Rhone whites. There's also Viognier, which is used predominantly in the Northern Rhone.

Green fruit and citrus notes are not uncommon in the major white wines of France so this will not help you detect Grenache Blanc in a blind tasting (if you ever get the chance to do one, you should, they're terrific fun), but one note I noticed when tasting in the region in Spring 2021, was fennel.

Out of the also-rans, I would keep an eye on Clairette. The winemakers I met all admired its ability to withstand heat and preserve acidity in a region that can only conceivably become hotter. Clairette wines have a freshness to them which is a real bonus in a region where heat can overcook grapes, and it's not hugely alcoholic, which is a bonus for any Rhone blend.

Lockdown Michelin heaven

You can easily find a place to stay in any of the Rhone villages. There are Airbnbs everywhere. Pick your favourite cru or village and knock yourself out. But if you want a bit of a gourmet break, you can do a lot worse than Entre Vigne & Garrigue in Pujaut, just a handful of kilometres north of Avignon. So many Rhone wines are bold, and that invariably means you will need food to complement them. Serge Chenet's Michelin starred oasis is the place to enjoy both.

My main was a supreme of organic chicken stuffed with foie gras and morels served with spelt risotto.

I picked a white wine from nearby Uzes, made from Grenache Blanc, Marsanne and Viognier to accompany. Absolute heaven.

I took a room overlooking the lovely terrace and garden, with large pine beams and a glorious stone wall. Available at 165 euros in low season and 195 in high season. And for an extra 60 euros you can treat yourself to a special room service menu (wine not included). Highly recommended.

Libyan wine?

Probably more than any other region in France, the Southern Rhone is home to the co-operative.

Organisations such as Rhonea and Maison Sinnae (named after Julius Caesar's first wife) represent hundreds of winemakers and guide them in terms of vineyard management as well as buying their grapes and making wine with them.

Claude Chabran is the president of Rhonea, a co-op that makes wine from the yields of 250 artisan winegrowers. He drives me up the hills above Beaumes-de-Venise to show me how the movement of the tectonic plates has forced soils that should be 500m beneath the surface of the earth to 500m above it. And though this is fascinating, and I yearn to know more about how Triassic era soil might affect the taste of the Grenache that ends up in my glass, I am distracted by something else.

We get talking about his past. Where he had worked etc. Claude has been all over the Middle East and North Africa. He mentions Libya. I talk to him about the time I coordinated correspondents there and he opens up about his experience.

"I was in Benghazi," he says. "I was representing engineers on big building projects."

"Not a great deal of wine to be had in Libya," I venture, Libya being a dry country.

"Well, you say that. But there's always a way," he says, pulling his 4x4 away from a massive pothole that may have swallowed half the vehicle.

"There were grapes there. So I asked a local guy to make me a crude wine press. And he did a really good job. I knew how to make basic wine and although there wasn't much we could do with fermentation, we made something close to wine and drank that for a while."

Claude was doing this while Gaddafi was running Libya, and ran the risk of imprisonment. But he clearly wasn't phased by this, and moreover was not the only one trying to make some form of enjoyable alcohol.

"The British were the funniest," he recounts. "One of them had a book which set out how to make wine from carrots and celery. They would drink absolutely anything."

From those Triassic heights, I could see as far as the hills and plains of Gigondas, which is a must-see if you come to the Southern Rhone.

Gigondas - Village of Joy

The symbiosis of warmth and freshness epitomises the wines from this special Rhone Cru as well as the weather, but perhaps the real associative success story here is the relationship between this microclimate's winemakers and their unique terroir.

Jocunditas was the name of this centuries-old Gallo-Roman village. It translates from Latin as 'pleasantness', which is a good start. This gradually became standardised, via Jocundaz and Gigundaz (and a few others) to Gigondas throughout the Middle Ages when it became a popular hunting ground for the Princes of Orange. And while hunting dogs are still trained en masse within the environs of the town, the real game here is winemaking.

There is much mention of the word 'harmony' when I talk to winemakers all over France. An understanding of nature, and the submission to her forces. Here, there seems to be more of it. As the world of wine moves, inexorably it seems, towards more natural methods of farming, the southern Rhone could make a claim to be the early standard-bearer.

I head to Pierre Amadieu winemakers for a tour of the terroir.

We are 350 metres above sea level on the heights of Gigondas, and you can feel the breeze.

"This is the Mistral," says Jean-Marie Amadieu, winemaker, as he surveys a domain owned by his family since his grandfather began trading in 1929. "You feel it, always, this cool breeze. It's great because it's always refreshing the vineyard and regulating the temperature of the vines. It also dries the vineyard, avoiding the diseases we can have during spring like mildew and rot."

These are conditions where the use of pesticides is not necessary. Here you are almost able to be organic without drastically changing the way you take care of your vineyard.

While many vineyards in Europe crave a south or south-east facing aspect, here the sought-after face is the north, and altitude is a real plus. But with all this cooling, does he worry about ripeness?

Only with the Mourvedre, he says.

"In the 50s noone was planting Mourvedre because we didn't have so much global warming and so Mourvedre didn't get very ripe. We never got ripeness on it. My grandfather tried it and was frustrated."

I venture that Jean-Marie's grandfather may have been a visionary. Planting a grape that would only ripen in a predicted future where temperatures rose and ripeness in this varietal was possible.

Amadieu enjoys the idea, and goes with it. "Yes maybe he was a visionary!" he laughs. "We have a wine which is almost 30 percent Mourvedre from these vines my grandfather, Pierre Amadieu, planted in the 50s, and it's delicious."

I ask him when his family saw climate change in action.

"It was between 2000 and 2005. We started noticing lower acidity, higher alcohol and sugar and the date of the harvest was earlier. In the 90s we started on 10 October. Last year we started harvesting on 28 August. It's crazy."

All good things must come to an end of course, and these 1950s vines are approaching the end of their lives. But replacement has already begun and will take place over more than a decade. Interestingly, the biodiversity element was already in play when Pierre Amadieu and his son expanded the family vineyard from 7 hectares to 130 over two decades in the 60s and 70s.

"The first thing my grandfather did was to buy the land from the church. Then he bought sheep to begin cultivating the land. There are olive trees too, they're still here," says Jean-Marie. "We found an old machine to deal with the grass and the weeds and we now use that to farm this land."

Pierre started putting Gigondas on the bottle to let people know that it was from this special area (there was no AOC Gigondas back then) and not just a regular Cotes de Rhone. The wine was kept in beer casks from Alsace that the family bought in 1890. He believed the terroir was unique and his beliefs have been entirely vindicated. It's a special place.

As we look out over these ageing vines, the plate tectonics provide yet another fabulous theatrical backdrop. The horizon is rock, dropping, rising and plateauing like a line graph charting recession and boom. The almost-rounded dip to the southeast is called Le Pas de l’Aigle - the eagle's pass. And it's the wine of the same name that catches my attention back at Pierre Amadieu HQ. 90% Grenache and 10% Syrah, this wine spends 2 years in French Oak barrels and at least one more year in the bottle. It has a freshness about it, and that most essentially French of aroma notes, 'garrigue'. For English speakers, garrigue is a kind of 'mixed herbs' terms that engenders the scrubland of southeastern France, encompassing the ubiquitous lavender with juniper, sage and rosemary.

The estate is currently in conversion to organic farming. 40 hectares are already organic and, thanks to the climate and the Mistral, there's no problem with rot or grape viruses, so they don't need to use insecticides.

Over the Rhone in Lirac, I met Richard Maby who taught me that some winemakers can be primadonnas. But in a very particular sense. Richard, who is in reality far from arrogant, is a huge opera fan and names his wines after famous operatic terms.

In his vineyard I finally set eyes upon the absolutely enormous stones, called galets, resembling huge potatoes, that populate so much of the terroir around here. The Southern Rhone is famous for these ludicrous, oversized pebbles. I fell in love with his Casta Diva, which is a mix of Grenache Blanc and Viognier but the melange is aged in oak. And new oak at that. The varietals are big enough to deal with new oak (which is full of flavour) and imbue the finished product with tasty notes of elderflower, pear and apricot. Obviously, he didn't leave the classic Three Tenors favourite out of his repertoire, so his Grenache, Syrah and Mourvedre model is called Nessun Dorma. Vin...cero.

Throwing out the blazers and ties

Lirac is next to the famous Rhone AOC called Tavel. A unique area in French winemaking as it is concentrated solely on rosé wines. Here I met Francois Dauvergne and Jean-Francois Ranvier, the two figureheads behins R&D wines.

They reside in a funky, ecologically conscious headquarters. They are the first and the best (and, they modestly tell me, the only) negociant in Tavel. Everything is geared towards sustainability. From the regulation of temperature in the barrel room to the solar panels on the roof, D&R are ahead of the curve environmentally.

Talking to these two guys, both passionate, learned and convivial, one understands that the Rhone is a very serious winemaking region, with extraordinary complexity, history and variety. These are not just country wines of mixed quality, these are wines that can be as fascinating as anything from wine regions that are, arguably, thought of as superior or, dare I venture, flashy.

"We don't have the global image of Bordeaux. We don't wear blazers and ties. We have our feet in the mud, not in a Jaguar," says Dauvergne. He thinks Bordeaux will be "compelled to evolve" and I think he has a point. There's so much money and expectation on the banks of the Gironde, that it's hard for winemakers there not to become the stereotype. But is this sour grapes? Maybe not. The reputation of Rhone wines is on the rise. The unique terroir of each appellation is being increasingly understood and negociants like these two are obsessed with finesse and take care to express these unique geographical and geological nuances. They produce wines from all over the Rhone Valley in a truly expansive catalogue. You can't tell me these guys don't have blazers...

I drink their 'Face Sud' Cote Rotie with farm chicken and morels. It's stunning. A glass basket of figs, cherries and violets. But this is top of the range syrah. What about the local stuff?

"Grenache can age like pinot noir," says Dauvergne, pouring an organic Côtes du Rhône. "It can be delicate and pale but full of flavour, with an ability to age." Its nose redolent of roses rather than the violet you might expect from a red Burgundy. It's not an aggressive power, it's reserved. It's rather like François and Jean-François, I suggest to them.

"That is the best compliment we can have. As we put our names on the label, we try to have wines that are coherent with our way of thinking. It's something," he hesitates, "that is a little bit intellectual. But it's a wine, it's not a thought..."

But it is a thought, just as philosophy is thought. The most interesting wine is made by growers and producers who are driven by ideas, by convictions, by that certainty that this unique terroir can be expressed by using factors both natural and human.

Caesar's camp, which is the name of the ruined former city overlooking Laudun rather than a judgement on the Roman leader's demeanour, still stands 2,000 years after his death. The same wind clears the air in the 21st century and will go on protecting the vines from being conquered by disease long into the future. But for now, as France begins its stilted journey out of the silence, this warm, easy-going and welcoming wine region is there to be discovered.