Mpox, formerly known as monkeypox, is endemic in central and western Africa and was last declared a global health emergency in 2022.

Mpox has been declared a global health emergency for the second time as an outbreak spreads in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and neighbouring African countries.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The World Health Organization (WHO) decision this week to declare the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) will likely spread awareness about mpox and increase measures to respond to it, experts said, warning of the importance of early intervention.

Here’s what you need to know about mpox and the most recent health crisis.

What is mpox?

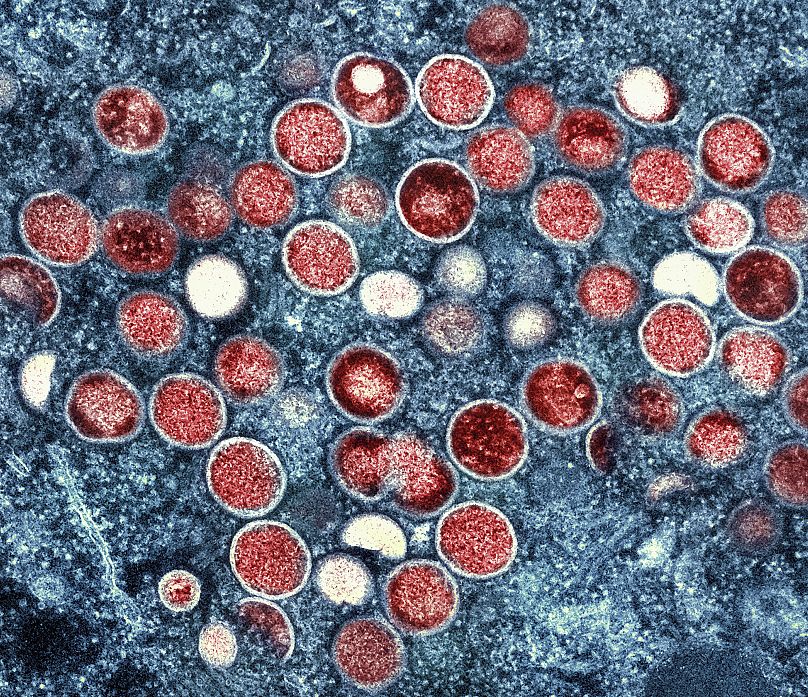

Mpox, formerly known as monkeypox, is caused by a virus of the same name and was first discovered in monkeys used for research in 1958, according to the WHO.

The first human case was reported in 1970 in what is today the DRC. The virus is now endemic in countries in central and western Africa but caused a global outbreak in 2022 in countries that had not previously reported cases, such as in Europe.

There are two subtypes of the virus, known as clades. Clade I, which is endemic in central Africa, is thought to cause more severe illness. The 2022 outbreak was caused by clade II, which is endemic in West Africa.

There’s also a new strain in the eastern DRC and some African countries related to clade I, called clade Ib that is of concern. This new strain “appears to be spreading mainly through sexual networks,” according to the WHO.

How many cases are there?

The Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), which also declared mpox to be a health emergency this week, said that the number of suspected mpox cases across the continent has passed 17,000 this year.

Most cases are in the DRC, but there is limited testing in rural areas, with just 24 per cent of suspected cases in the country tested this year, meaning the number could be higher than those in official reports.

More than 500 deaths, mostly in the DRC, have been confirmed, according to the Africa CDC.

At least 13 African countries are impacted, including those that had not previously reported mpox cases until recently, such as Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda.

On Thursday, Sweden's public health agency said they detected the first case of clade I outside the African region. The person had recently travelled to an area in Africa where there was an outbreak.

What are the symptoms of mpox?

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “people with mpox often get a rash that may be located on [the] hands, feet, chest, face, or mouth or near the genitals”.

The rash can go through different stages and may look like pimples or blisters, the CDC said.

Other symptoms can include fever, headache, chills, physical weakness, lymph node swelling, muscle or back pain and/or respiratory symptoms, according to European and US health authorities.

A WHO situation report from earlier this week said the most commonly reported symptom is a rash, followed by a fever and a systemic or genital rash.

The virus can spread by direct contact with infected wild animals or through close contact with an infected person, including sexual contact, which is the most commonly reported form of transmission globally.

The spread of clade II, in particular, was driven by sexual contact primarily among men who have sex with men, while clade I was first documented as spreading sexually last year.

How will the WHO declaration impact the situation?

“It's a positive response because it will bring about a lot of action on the part of government,” Jaime Garcia-Iglesias, a chancellor’s fellow at the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Biomedicine, Self and Society, told Euronews Health.

He pointed out that a lack of diagnostic means and vaccines in Africa have contributed to the outbreak.

“The [WHO] declaration is important because it will galvanise efforts. It will get government into action,” he said, adding that there was a need for funding for research and diagnostics as well as appropriate messaging for communities.

Experts say there is also a need for more information about the virus and its impact.

“It can be a very dangerous infection and there have been deaths, but to understand the mortality rate we need to understand better the number who are infected overall, including those with milder disease and how infected they are,” Trudie Lang, a professor of global health research at the University of Oxford, said in a statement reacting to the WHO declaration.

“This disease impacts highly vulnerable communities and there is already much stigma associated with this,” she said, adding that there is a need to understand people’s perceptions and practices for effective public health interventions.

How can mpox be prevented?

Garcia-Iglesias told Euronews Health that countries should prepare by working and engaging with communities before another crisis.

“We need governments to actually engage with community organisations, community leaders now to prepare those relationships in case we need to mobilise them to develop messages. We also need to build capacity, particularly around sexual health clinics, if we think that sexual transmission is going to be the main route which we don't know yet,” he said.

“Two years ago, sexual health clinics were past breaking point really, and we saw massive decreases in the provision of other essential sexual health services like PrEP (for HIV prevention), in the UK,” he added.

Experts have also called for a global response to the outbreak and urged countries not to hoard vaccines as they previously did during the COVID-19 pandemic.

While there are two existing vaccines in use for mpox, there is a need to increase access to them, WHO said.

“The current upsurge of mpox in parts of Africa, along with the spread of a new sexually transmissible strain of the monkeypox virus, is an emergency, not only for Africa, but for the entire globe,” said Dimie Ogoina, a Nigerian infectious diseases expert who chaired the committee advising WHO on the decision to declare a health emergency for mpox.

“Mpox, originating in Africa, was neglected there, and later caused a global outbreak in 2022. It is time to act decisively to prevent history from repeating itself,” Ogoina added.