In this episode of Smart Health, we travel to Ireland to hear from a family whose life was turned upside down by Alzheimer's and find out what the EU is doing to help the 8 million Europeans who suffer from the disease.

Back in 2015, retired civil servant Gerry Paley started to feel and act differently. He was 59. He was diagnosed with Alzheimer's, the most common form of dementia.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

"I forget things. I had to walk somewhere and took a message and I could not remember what the message was," he told Smart Health.

"I think Gerry kind of lost his confidence," explained Gerry's wife, Nuala. He wasn't sure of what he was doing any more. He was making big mistakes when doing things. He was missing very logical stuff."

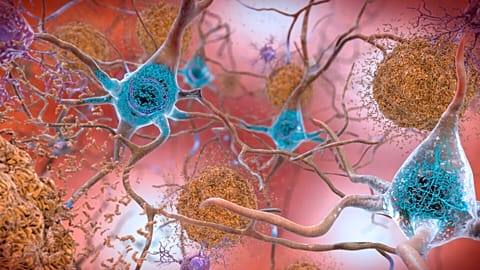

The disease has no known cure. Existing medicines available in Europe can only help treat symptoms related to memory or behaviour.

"Medication is doing well for me. I'm walking all the time with my dog, and [I'm] outdoors all the time. So exercise is good," said Gerry.

Gerry lives near Dublin, Ireland's capital. He is one of the some 8 million EU citizens living in the labyrinth of dementia. This number is expected to almost double by 2050.

With no cure at hand, patients can only rely on daily activities to try to improve their quality of life. The Orchard Respite Centre in Dublin provides services to some 30 people living with dementia.

"People who have this condition, they can live up to 25 years," revealed Mary Hickey, the manager of the Centre. "They want to have a quality of life. We would always recommend that people see their consultant every six months and get a medical review. Sometimes we can even see the need for that from here, and we can recommend people to return to their care team," she added.

The development of therapies which can prevent or slow the progression of dementia is an active area of research, with promising medicines currently in development. But relevant breakthroughs are still elusive.

The European Commission has proposed a legal framework to encourage medicine developers to invest more in what is known as Unmet Medical Need (UMN), like Alzheimer's.

The primary incentive is an additional six months of data protection for those products.

Developers who deliver would also be eligible for strengthened scientific and regulatory support, explains the European Commissioner for Health, Stella Kyriakides.

"What we need to do ultimately is to support innovation, because that is what will benefit patients with challenging diseases like Alzheimer's and others. And you need to make sure that you are developing new medicines all the time."

The European Commission and experts agree that once medicines are developed, the European Union should also ensure all patients can access them.

"There is no point in us having these breakthroughs which are hopefully on the horizon and our health systems in Ireland and across Europe aren't ready. Because these drugs will be very expensive for people to access," Cormac Cahill, the Head of Advocacy and Research at the Alzheimer Society of Ireland told Smart Health.

"So we need to think how we are going to pay for them, how we are going to get our health systems ready. And this work needs to start now," he added.

Gerry and Nuala just hope this work will prove effective.

"It is costing a lot of money to research, to have medication...[to keep people] in hospitals," said Gerry.

"If it was diagnosed earlier, and which it should be, if you go to a doctor when you are a child and you are progressing, the doctor should be able to see if something changed in the person and then they can catch it early rather than let it happen when you are older. It's too late then. All you can make is to have your medication to keep yourself... on a level," he concluded, adding "If we could have proper medication, we could be able to solve the problem."