The world-famous photographer Rankin speaks to Euronews Culture about his latest project on haemophilia, shooting the Queen, and how he's come to understand human condition.

“When someone has any form of terminal illness, or has gone through a near death experience,” Rankin tells me, “their unique celebration of life is palpable.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

When you’re a photographer who’s taken pictures of endless popstars, models and even the Queen, what’s the next project on your agenda?

Rankin is one of the world’s most successful portrait photographers. He’s shot for Elle, Vogue, Esquire, GQ, Rolling Stone, Wonderland and, of course, his own publication Dazed & Confused.

But for his latest project, he’s not taking pictures of the Rolling Stones or Miley Cyrus. He’s been taking photos of haemophiliacs.

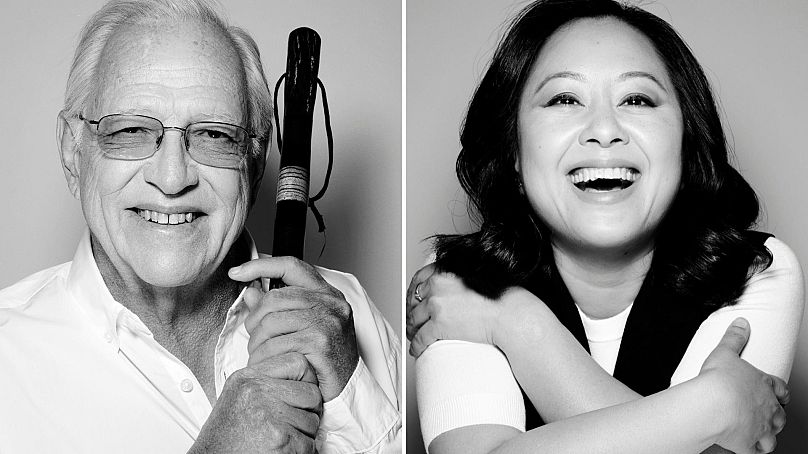

More specifically, Rankin’s latest project has been creating portraits for haemophilia sufferers for a new awareness campaign ‘Portraits of Progress’.

Portraits of Progress

Haemophilia is a rare disease that affects one in every 5,000 (Haemophilia A) to 30,000 (Haemophilia B) male births.

The campaign looks at the progress of treatment for haemophilia from its identification in the 1940s to those who live with the disease today.

Rankin has documented a group of haemophilia patients and their journeys. On the face of it, the project is a far cry from how many people would have come across his work.

“I’m always interested in the human condition,” Rankin says. “As a photographer, it’s my bread and butter.

In recent years, Rankin has increasingly taken on charity projects, using his work to highlight causes he cares about. He’s grown awareness for Macmillan Cancer Support and endometriosis, as well as many other causes.

When he learnt about haemophilia though, he was struck by the severity of a disease he thought he understood.

“I had no idea that the average age of somebody before medicine was only 20,” he tells me. Finding that out made him see the importance of the story’s positive impact.

“If I'm photographing people that are over 20, essentially, they're miracles of modern medicine,” he marvels.

Only human, after all

Many big names have stood before Rankin’s lens from musical royalty like David Bowie, through to modelling royalty Kate Moss, to just plain royalty.

The goal of the project remains the same, regardless. Rankin’s trademark glamorous style is an opportunity for someone to be captured at their absolute best. To do this he works alongside the person, making them comfortable and letting them even choose which picture is the final image.

“What I'm trying to do is take what I do with celebrities, and apply it to people that aren't celebrities to give them that iconic status,” he says. “You want them to walk away feeling like they've got a great picture of themselves, it really represents them.”

It may sound innocuous, but it’s a definitive marker of Rankin’s style. Rarely does he go in for the gruff candour of some photographers. Instead, he leans into the portrait as a celebration.

“I’m always trying to get the best out of the person,” he says. “Yes, there might be a positivity which people can think of as glossy or whatever, but I’m never looking for the negative.”

While he accepts his style is celebratory, he doesn’t concede that it puts the subject on a pedestal. Rankin instead believes a celebratory eye can best create an image that the subject sees themselves in.

“I want the person to look through the lens and really connect with the audience, and almost for the lens and what I'm doing with it to disappear. My goal is to have a relationship between the photograph of the person and the person looking at it. I’m a conduit for that,” Rankin says.

Papping the Queen

The way to get that perfect shot is as variable as the people he works with. When it came to shooting his iconic image of Queen Elizabeth II in 2001, he’d spent the last 15 years photographing bands in five minute slots at their hotel rooms.

“I was super nervous about photographing her, because she was the most famous person in the world,” he admits. “But, you go to the lowest common denominator, which is, she’s a human being. So that's where you try to just connect with them on a human level.”

They quickly got on and Rankin noted her sense of humour. When she laughed as a piece of his camera fell off during shooting, he saw the humanity he was looking for.

The shoot was a success and he sent off three versions for the palace to authorise. For the final picture, Rankin placed a Union Jack behind her as a cheeky homage to Jamie Reid, the anarchic artist who designed the Sex Pistols logo.

“At the same time, I was a really big fan of her as a person. So I was kind of playing with the idea of her being an icon, that beneath the surface is a human being,” Rankin explains.

Rankin’s sense of humour has often come in use for a shoot. “Madonna said to me, I chose you, because in the photographs you take, people look like they’re having a good time in them,” he says.

“So, then you have to be a stand up comedian for Madonna,” Rankin says.

The man behind the lens

It all leads to the fundamentals of Rankin’s philosophy for his art. He doesn’t want to be selling products, or advertising or marketing. “We're selling humanity,” he says.

But where’s Rankin’s own humanity in all of this? As he tries to capture each person on their best day, the fingerprint of the artist’s own humanity is surely going to make its mark.

While he notes that over the course of a career he can remember shoots where he was having a difficult time, but he has no interest in documenting his own thoughts of a shoot outside of the picture itself.

“It feels a bit like you're a kind of priest,” he says. “I'm not religious, but there's a circle of trust, or a FriendDA,” he jokes on the topic of Non-Disclosure Agreements.

Despite his self-admitted big personality though, Rankin believes his efforts to collaborate with his subjects give them an autonomy and control over their work that subdues the effect of his portfolio’s subject being ultimately the artist himself.

“My power has been in coming together, not taking from people. I was brought up really well. I think my parents would never want me to take anything from someone,” he says.

The choice to take photos for the haemophilia project fits neatly into his philosophy.

"I think that there is a play with being iconic. I think taking haemophilia sufferers who go through hell and making them stars and icons, and putting them on the same level as a celebrity, I find that really interesting,” Rankin says.