How do helicopters help winegrowers stave off freezing temperatures in spring?

French vintners are always looking for new ways to thaw their grapevines to save them from a late frost following a winter warm spell, a temperature swing that is threatening fruit crops in multiple countries.

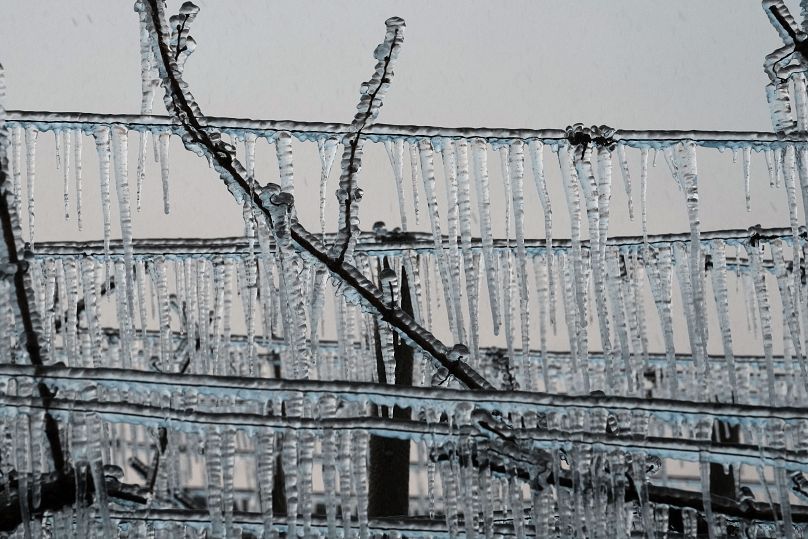

Ice-coated vines stretched across hillsides around Chablis as the Burgundy region awoke Monday to temperatures of -5 C (23 F). Fruit growers are worried that the frost will kill off large numbers of early buds, which appeared in March as temperatures rose above 20 C (68 F), and disrupt the whole growing season.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The frost is particularly frustrating after a similar phenomenon hit French vineyards last year, leading to some 2 billion euros ($2.4 billion) in losses. Scientists later found that the damaging 2021 frost was made more likely by climate change.

Before dawn on Monday, row upon row of candles flickered beneath the frosty vines in Chablis. As the sun rose, it illuminated the ice crystals gripping the vines.

While some vintners use what they call candles (paraffin drums that they set alight), others try to warm the vines with electrical lines or sprayed the buds with water to protect them from frost.

The helicopter method

Further south on the Cote de Beaune, helicopter pilot Caroline Schiel has to wait for the aeronautical sunrise, which is half an hour before the actual sunrise, to begin her rounds.

She works for Mont Blanc Helicopters and has been hired along with her small Robinson helicopter by a local winemaker to warm the air around the vines.

"We get to the vineyards and try and figure out where the inversion level is (the point at which the air is a few degrees warmer) because the temperature is inverted when there is high atmospheric pressure. On the ground level it's freezing, or below freezing, and then up at a certain level it starts to get warmer."

"It can be anything from five metres to 50 metres above ground level. And then we fly low enough for the air to get sucked into the rotor system, and it gets pushed down below. So we're sucking in warm air and pushing it down below. The engine of the helicopter is warm as well, so we're blowing air over the warm engine and onto the vineyards."

Finding the inversion point

"We've got a team on the ground who collect temperatures on each parcel (individually owned sectors of the larger vineyard which often, in Burgundy, has multiple estates owning different parts) and we're hovering. We have a thermometer in the helicopter, an outside air temperature reading, and we just get higher and higher and as soon as we see the temperature getting warmer, that's the inversion level."

"Some parcels this morning were even minus-five," she told Euronews Culture.

"We flew for about two hours, taking off at 6:45 am."

With the way Burgundy is structured, it's nigh on impossible to only warm up the client's parcels when you're hopping from one parcel to the next, so the helicopter method often has a by-product of warming other winemakers' sectors unbidden. This isn't always welcome despite it sounding like a bonus.

"It's a delicate topic of conversation between winemakers," Schiel admits. "Those that don't use helicopters put these paraffin drums every couple of metres throughout the vineyards, and that warms up quite well."

"But the problem with this is you're burning paraffin which is not very ecological. It gets very smoky. There have been years where we've flown and there's so much smoke that we've had to stop flying. It's very beautiful, but it's not very eco-friendly."

Schiel says that some of the other owners are vexed and accuse her and her client of 'stealing' their hot air that they created from the bin burning.

"Others are happy that we're blowing their hot air down again, because, obviously, hot air rises," she says.

How costly is it?

"My client is convinced that it's not more expensive than buying these paraffin drums, plus you need to employ staff to go out, set them up, and then light them early in the morning. They have about 8 hours of burning time. So they can use them for about two days, then you'd have to replace them all again."

Winegrowers can expect to pay upwards of around 1000 euros per hour to employ someone to use the helicopter method. The bigger the machine, the greater the cost. So it's a matter of calculation.

There could be a hybrid solution by using both and spreading out the paraffin bins, using fewer of them.

But in terms of fuel and footprint, Schiel is sure that even though on paper, helicopter vs 'candle' sounds like a no-brainer, her method is less ecologically damaging.

"Some people say 'how awful, you're flying helicopters over vineyards', but when you have to fly in the smoke of burning paraffin, that's not ecological at all. The helicopter is much cleaner. We burn one litre of fuel per minute and then you see how many litres of paraffin they're burning in the vineyards, you can't compare."

In Switzerland, local media say the country's crop of pitted fruits such as apricots, prunes and cherries is at risk from the icy spell.

The below-freezing temperatures are causing similar concerns about potential damage to apple and other fruit orchards in Belgium and the Netherlands.

Last year's April frost led to what French government officials described as “probably the greatest agricultural catastrophe of the beginning of the 21st century.” The pattern was similar: an intense April 6-8 frost after a lengthy warm period in March.

Researchers with the group World Weather Attribution studied the effect of the 2021 frost on the vineyard-rich Champagne, Loire Valley and Burgundy regions of France, and found the March warmth made it particularly damaging.

The researchers concluded that the warming caused by man-made emissions had coaxed the plants into exposing their young leaves early before a blast of Arctic cold reached Europe in April.