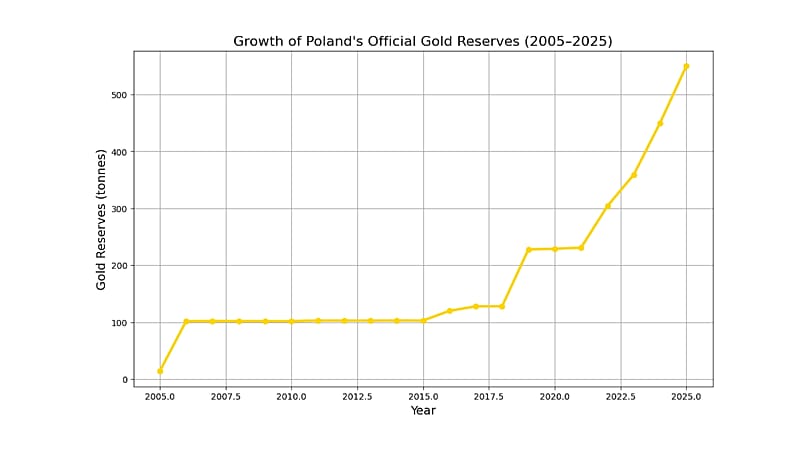

The National Bank of Poland has increased its bullion reserves to around 550 tonnes, valued at more than €63 billion.

The President of the National Bank of Poland (NBP), Adam Glapiński, has emphasised for years that gold plays a special role in the structure of reserves.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

It is an asset free of credit risk, independent of the monetary policy decisions of other countries and is resistant to financial shocks.

High gold reserves also contribute to the stability of the Polish economy.

The bank's ambitions are far-reaching: the target is to have 700 tonnes of gold and the total value of bullion reserves to be around PLN 400 billion (€94 billion).

As recently as 2024, gold accounted for 16.86% of Poland's foreign exchange reserves. Estimates at the end of December 2025 showed a jump to 28.22%, marking one of the fastest changes in the structure of reserves among central banks worldwide.

The largest transactions were carried out in the final months of 2025, during a period of heightened market volatility and geopolitical tensions.

On the initiative of Glapiński, the NBP's management board has decided to further strategically increase the share of gold.

Glapiński announced earlier in January that he would ask the board to adopt a resolution to increase reserves to 700 tonnes of bullion.

Investing in gold

According to analyses by the World Gold Council, 2025 brought a continuation of the global trend of gold accumulation by central banks. With few exceptions, most countries increased their holdings, treating bullion as a strategic hedge against currency and financial crises.

In 2025, as many as 95% of central banks surveyed expect global gold holdings to increase over the next twelve months.

The reasons why central banks invest in gold are explained by Marta Bassani-Prusik, director of investment products and foreign exchange values at the Mint of Poland.

"One of the key motivators for central banks is the independence of the gold price from monetary policy and credit risk. Equally important is asset diversification and reducing the share of the dollar and other currencies in reserves," she explains.

Experts point out that not all central banks report the full scale of their purchases. China or Russia are often pointed to in this context. Some market observers interpret these actions as part of preparations for an alternative money model, in which gold could play a much greater role than before.

More gold than the ECB

The information that Poland now holds more gold than the European Central Bank (ECB) is not only symbolic. The ECB manages the monetary policy of the eurozone, but its own gold reserves are relatively limited and the burden of owning bullion lies mainly with the national banks of the member countries.

The ECB's gold reserves amount to around 506.5 tonnes. Against this background, the scale of the NBP's holdings - 550 tonnes - is impressive and strengthens Poland's position in the European financial architecture.

However, critics of the NBP's extensive acquisition of gold point out that the funds earmarked for the purchase could be placed in bonds, which generate interest income. Indeed, gold does not provide current income.

Record prices and forecasts for 2026

The NBP's purchases have coincided with historic records for gold prices. Although the rate of listing growth may slow down in 2026, forecasts from major financial institutions remain optimistic. ING estimates an average price of around $4,150 per ounce, Deutsche Bank says $4,450 and Goldman Sachs raises its forecast to $4,900. In a scenario of strong global demand, J.P. Morgan allows for as much as $5,300 per ounce.

"Rising demand from central banks is a response to economic tensions and dynamic geopolitical changes. Although institutional purchases do not directly translate into prices, they indirectly influence the decisions of individual investors," Bassani-Prusik emphasises.

Gold returns to the favour of investors

For the NBP, gold is an element of the country's long-term financial security strategy.

As Mint of Poland experts note, the greater the uncertainty in the markets, the greater the interest in assets perceived as a "safe haven." There is also a growing awareness among retail investors of the role of gold in long-term capital protection.

However, some economists oppose this thesis and feel that a high proportion of gold may not meet the needs of flexible reserve management in a modern economy and funds could be better allocated in other, more productive investments.

Reaching 550 tonnes is an important milestone, but announcements of further purchases suggest that Poland has not yet said its last word. In a world of rising geopolitical tensions and a changing financial order, gold is once again becoming one of the key assets and Poland wants to be at the forefront of this game.