All you need to know about the Iran protests and the death of Mahsa Amini.

What sparked the Iran protests?

Iran has been rocked by the biggest protests in years following the death of Mahsa Amini on 16 September.

The country's morality police -- tasked with enforcing strict codes around dress and behaviour -- had arrested the 22-year-old for allegedly not wearing her hijab correctly and sporting skinny jeans.

Her family say Amini was beaten and her head struck several times. Officials have denied these accusations, claiming her death was due to an "underlying disease".

Who is protesting?

Demonstrators reject this official line and protests are still happening across the country.

Iranians of all ages, ethnicities and genders have joined in the demonstrations but it is mainly younger generations that have taken to the streets.

“Women started this wave of protest,” says Ramyar Hassani, spokesman for the Hengaw Organisation for Human Rights.

“But everyone else joined. Women and men are shoulder-to-shoulder. All of Iran is united.”

"For the first time in the history of Iran since the Islamic Revolution, there is this unique unity between the ethnicities. Everyone is chanting the same slogan. Their demand is the same."

What form have the protests taken?

Nearly every type of “peaceful, non-violent” protest has been used in Iran, says Hassani.

In large street demonstrations, which have happened in all of Iran's major cities and many small towns, women have burnt their hijabs, often dancing at the same time, while others have cut off their hair.

Strikes have been reported in schools, universities and the country’s vital oil sector, while shops have repeatedly shut their doors.

Iran's football team refused to sing their national anthem at the World Cup in Qatar on 21 November and fans have chanted slogans against the regime outside of stadiums.

One key chant is 'woman, life, freedom', a phrase rooted in the Kurdish liberation struggle that has rung out on the battlefields of Syria.

Violent clashes have at times broken out inside Iran, with protestors torching buildings of the security forces.

Demonstrations also spread to Europe. Women from Stockholm to Athens have lopped off their locks to show solidarity.

How has the regime responded?

Security forces cracked down on protestors "very violently" from the beginning, especially in areas where ethnic minorities live, such as Kurdistan and Balochistan, says Hassani.

People have been shot for honking their car horns in support of protestors, while swathes of journalists (including those who first reported Amini’s death), lawyers, celebrities, sports stars and civil society figures have been chucked behind bars.

As of January, at least 522 people, including 70 children, have been killed and several hundred injured, according to the US-based Iran Human Rights Activists News Agency. More than 20,000 people have been detained.

But these figures are likely to be much higher as much goes unreported.

Iran's government says more than 60 members of the security forces have been killed.

In Kurdish regions, troops, heavy weaponry and military vehicles have been deployed to quell protestors. Here Hassani claims people have been killed indiscriminately, adding that warehouses were used to detain people as jails filled up.

He also received evidence that 50 calibre machine guns were fired on civilians in parts of Kurdistan. This type of weapon is typically used in war zones, with bullets measuring 138mm from top to bottom.

The regime has accused foreign states, such as the US (which it calls the “Great Satan'') and Israel, of stirring up dissent, though there is no evidence of this.

Iran's top judge in November called for the "main elements of riots" to be given harsh sentences, saying now was the time to "avoid showing unnecessary sympathy".

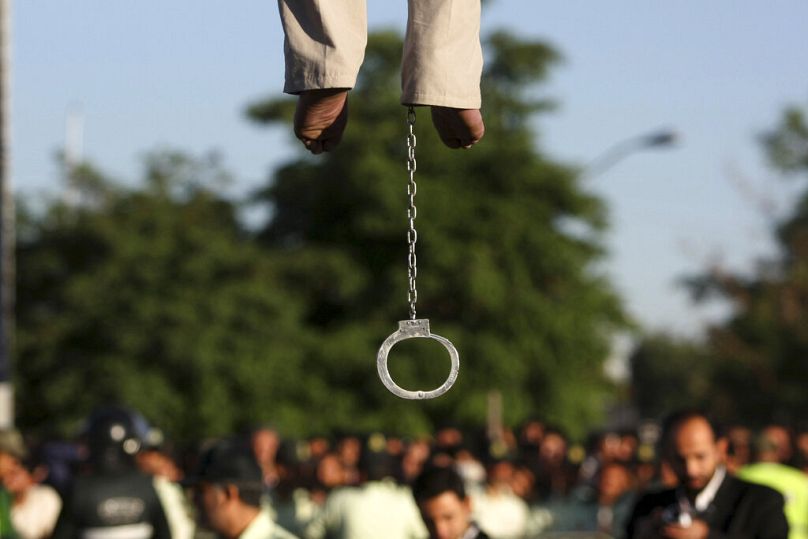

In December, the Iranian government executed the first protestor for so-called efsad-fil-arz (corruption on earth) -- prompting strong international condemnation. Four more people have been hung since then, though scores more face charges that carry the death penalty.

What's the context?

There is deep-seated anger in Iran over the government’s Islamic policies, especially those around dress code. Even when the hijab (headscarf) was made compulsory in 1983 there were protests -- dissent which has continued ever since.

Frustrations have worsened since hardliner Ebrahim Raisi became president in 2021 and began ramping up policing of women’s dress, says Roulla, an Iranian political activist and researcher, who wanted to protect his identity for security reasons.

Yet protests are also about the failure of reform.

“For decades, Iranians invested heavily in the idea promised by reformist leaders that things would change,” says Shadi Shar, an Iranian human rights lawyer.

“But nothing happened ... The message now is loud and clear, the Islamic Republic itself must go.”

Former presidents Hassan Rouhani and Mohammad Khatami tried to bring Iran closer to the West, lessen social restrictions and bring more democratic freedoms, though these efforts largely failed.

Adding insult to injury Iran’s economy has collapsed in recent years, while inequality has spiked.

“Young people on the streets see the sons and daughters of those in power having a luxurious life as their parents loot the people’s wealth, while normal Iranians see no future,” says Hassani.

After then US President Donald Trump pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal -- aimed at stopping Tehran develop a nuclear weapon -- in 2018, international sanctions were slapped on Iran and its currency went into freefall, with ordinary Iranians bearing the brunt of these economic blows.

What role is Iran’s Generation Z playing in the unrest?

Many protestors are young women and men – or those known as Generation Z.

According to Roulla, globalisation and the internet have led this group to protest by destroying "cultural differences between young people in the Middle East and Europe."

“When a young girl in Iran sees on social media that at the same time she has to go to a mandatory religious class, while people elsewhere are having a pool party … it's a comparison that cannot be unseen.”

In Iran, students must attend compulsory classes on Islam, with strict Islamic dress codes and gender segregation applied in schools and universities.

Why are these protests different from previous ones?

What is unique about today’s protests -- much larger and more prolonged than those in 2019 -- is that they have united nearly every section of society.

Roulla says that in 2019 poorer sections of society protested fuel price rises, while unrest in 2009 centred on more "middle-class issues" of vote rigging.

The “simple reason” why there is more unity now, he claims, is that Amini was an “ordinary girl”.

“She was not from a big city or an activist. She was taken from her family and murdered … it's much easier to sympathise with that.”

Something else that sets these protests apart from those in the past is that they show the Islamic Republic has “lost legitimacy among its core supporters”, says Sadr, believing this is due to the “horrific violence” inflicted upon past demonstrators.

“It's like internal bleeding inside the regime that is getting worse and worse.”

For the first time in recent years, anti-government unrest errupted in more traditional and conservative cities, such as Qom and Mashhad.

Is there anything Europe can do?

European Union foreign ministers slapped sanctions on Iran over its deadly crackdown in November. It targeted 29 individuals and three entities with asset freezes and travel bans.

Calls have been raised for European officials to do more and cut off diplomatic ties in an attempt to increase political pressure on the government.

While she hated to compare two “horrible situations”, Sadr said Iran needed the same action from the West that it had shown towards Russia over the invasion of Ukraine.

“Elites cannot continue to enjoy their normal life,” she said.

Iran is already one of the most sanctioned countries in the world. Exports of many goods, such as medicines and aeroplane parts, are blocked. The country is also frozen out of the world banking system.

According to Roulla, such sanctioning of "essential goods" had increased the power of an "aristocratic elite" by "making people completely dependent [on the state] ... allowing them to weaponise food and medicine".

"It's counterproductive," he added.

The impact of sanctions is debatable. Many argue they are an effective tool for putting political pressure on governments and changing their behaviour. Others claim they disproportionately affect ordinary people, create hostility towards those who enforce them and are seldom effective.

Could the protests topple the regime?

Observers are divided on whether the unrest could topple the regime.

Despite the violent crackdown, protests are continuing sporadically in what is now one of the biggest challenges it has faced since the 1979 revolution.

One important factor says Roulla will be if the regime stays united and parts of security forces do not defect. Iran’s last King fell in 1979 after mass defections from the army.

The protests leading up to his demise were on and off for months.

Roulla claims the regime is more divided than it seems with reports of internal tensions over how to deal with protestors.

In January, Iran executed former deputy defence minister Alireza Akbari, who had obtained British citizenship after leaving his post, for spying for the United Kingdom.

Cornelius Adebahr, a non-resident fellow at the Carnegie Europe research centre, said this possibly pointed to a "power struggle" among elites over how to handle the protests.

Akbari was seen as close to a government faction advocating for some reforms to address protesters' grievances.

Though unrest began with Amini's death, protestors now want the Islamic government gone.

Most observers agree that it has no legitimacy among large swathes of the population, who view the system as corrupt and broken beyond repair.

"Even if on the surface the regime will be able to crack down for a while,” says Hassani. “This is not going to be over."

"We have crossed the threshold of revolution."