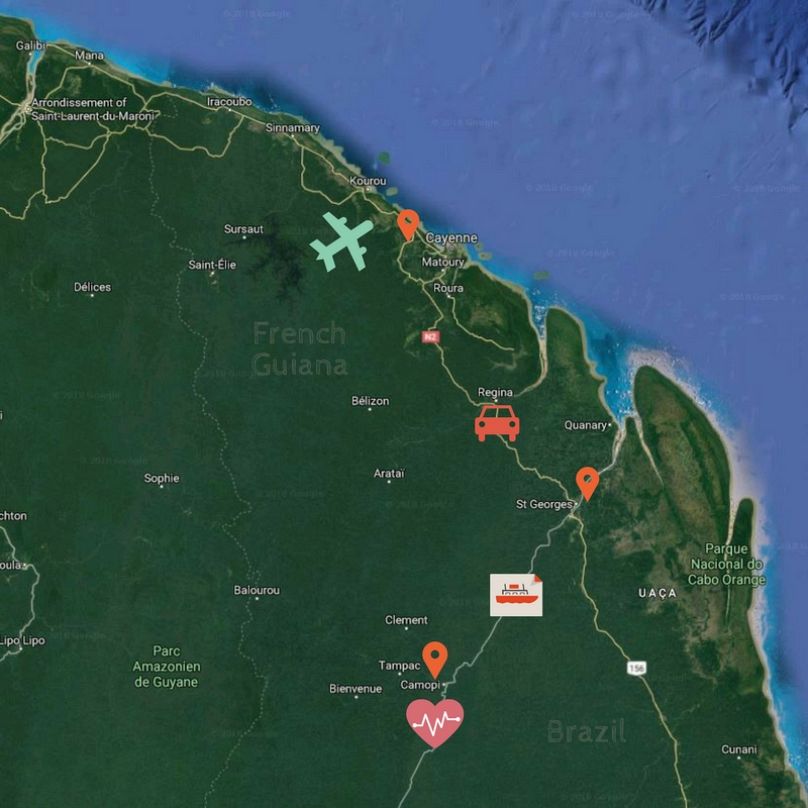

A nine-hour flight, four-hour drive and four-hour boat trip separates Nicolas Rombauts from his native France. Chasing an adventure, the GP trekked to a remote part of French Guiana to take up his post at a rainforest clinic, that has truly thrown him into the thick of it.

For doctors in search of an adventure, the Amazon rainforest can be just the spot. Clinics in remote parts of French Guiana are vital for the local population but filling positions is no easy task. One French doctor described his overseas mission, living and working far from the everyday luxuries most of us take for granted.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

A very long ‘commute’ to work

Nicolas Rombauts is a 33-year-old general practitioner from Lyon, who took a temporary position in Camopi, a commune in French Guiana. His clinic is located right on flood plains of the Oyapok River that forms the border to Brazil, and is surrounded by woods.

The nine-hour flight from Paris to Cayenne was just half the journey. Once in the French Guianan capital, Rombauts filled a car with enough food supplies to last two months and set off on another eight hours of travel by road and finally pirogue. The four-hour boat journey upstream on the Oyapock river during the rainy season was short by comparison to other times of the year.

During the dry season when water levels are drastically lower a trip like this can take twice as long as the boats have to zigzag along to avoid rocks.

A clinic run in five languages

At 10,000 square kilometres, Camopi is the third largest commune of the French overseas territory, but given its remoteness only 2,000 people live there. Six medics work in its small clinic on a permanent basis.

Communication can be tricky in the clinic. The indigenous populations in this region belongs to the Wayampi and the Teko tribes, each with their own language. Then there are also some Creole and a lot of patients make the trip over the river from Brazil. All in all, the clinic uses five languages to communicate with its patients.

The indigenous population does all speak some French but it is often not enough for the conversations doctors have to have with their patients. Both the care assistant and the clinic’s secretary are locals, and without their help translating, Rombauts confesses, he would not be able to help much.

“The work in the clinic has to be a teamwork all the time,” the doctor explains. The doctors’ knowledge has to be applied to the local environment. “While doctors come for their short missions and then leave, the care assistant and secretary ensure there is continuity and coherence in the medical care delivered.”

The clinic possesses an ultrasound scanner which has proven very useful, but for more sophisticated or special examination patients have to make their way to Cayenne. Soon, Camopi clinic might receive blood analysis equipment, which would have a huge impact on how quickly doctors can make a diagnosis. As it stands, blood tests can only be taken on one morning each week. The samples are then stored in an ice-box and set sail to a laboratory in Cayenne on a boat chartered by a hospital in the capital.

Flu, tropical diseases and delivery: It’s all in a day’s work

“Most of the time we are dealing with common illnesses and basic medical care that you would find anywhere in the world: routine care for children; immunization; infectious diseases like gastroenteritis, cold, flu, and some chronic diseases. Diabetes here is less common than elsewhere but it is catching up due to changes in lifestyle and food. The work is very diverse from a professional perspective because we have to deal with everything that comes up: pregnancies, emergencies, and some more severe cases”, says Rombauts.

He also has to deal with tropical diseases that he has previously had no professional experience of. In severe emergencies a helicopter will airlift the patient to Cayenne, provided one is available. But anyone in need of specialised treatment and able to travel will have to take the car and boat.

Pregnant women are supposed to go to Cayenne one month before their due date, but if the baby is premature or they leave it too late they end up giving birth in the clinic. If all goes well there is nothing to worry about but any complications are difficult to deal with.

Home is 16 square metres

Rombauts lives in a small wooden house which like most of the houses here is built on stilts. It has a bathroom, a joint living room and kitchen area, and a bedroom, though most of the locals sleep in hammocks under a mosquito net. Rombauts also has a hammock. It hangs on the terrace. All-in-all his living space is about 16 square meters.

“Life here is all over the place. I have geckos and frogs regularly showing up in my bathroom. The pumpkin seeds I planted sprouted well. I am now trying to grow local avocados, lemon and soursop,” Rombauts says.

The challenges of food shopping

The local diet consists of a lot of manioc – a shrub cultivated for its edible roots. It is used to produce Couac, a type of semolina. Rombauts says he has also tried cachiri - the beer locals make at home for parties.

Camopi’s population used to be entirely self-sustaining – hunting, fishing and growing crops on the fields located on patches of cleared forest. Now local stores stocked with produce from outside have crept in. The medics also shop there sometimes, though the shops are small and expensive. Everything sold in them comes from Cayenne and, before that, France.

Just across the river in Brazil, shops have far more variety. Rombauts and his colleagues sometimes canoe across to stock up.

“Once I bought a piece of a smoked paca from a Brazilian man,” he says. Paca is a large rodent native to South America. “I don't eat much meat for ecological reasons, but this comes straight from the nearby forest with the cute little paw attached to it. The cat loved it.”

Mangos, pineapple, coconuts, bananas, oranges, lemons, cashew nuts, sweet potatoes, and black pepper grow in the region. But unfortunately for Rombauts they are usually not sold in the markets or shops as most locals grow them. The doctor tries to purchase some whenever he can but his typical meal often ends up consisting of pasta with canned green peas that he sometimes ends up sharing with the cat hanging around his home.

Far from Wi-Fi

In his free time, the doctor mostly reads and writes. He didn't bring a computer with him and he is not missing out much since the internet connection is very slow. It helps fight his Youtube addiction, Rombauts says.

“One Saturday I went fishing with friends. Five of us left Camopi early in the morning in a motorized canoe to go down the River Oyapock. Navigating these waters is tricky, only experienced drivers can dare it as there are many invisible rocks just underwater, the boat’s propeller can be easily broken if they hit off them.”

For bait they used berries, he says, and the locals showed him how to throw the hook close to the shore, as if a fruit was falling from a tree. It wasn’t much of help though. “Many of my berries were eaten, but no fish ever agreed to jump on the boat.” The fish that were caught by his friends were grilled on fire made on a flat rock ashore.

There are 18 remote clinics in all of French Guiana, with around 20 general practitioners working in all of them combined. There are also around 80 other medical workers distributed across large areas, including midwives, nurses, and healthcare assistants. Two doctors coordinate their work. The most remote centre is located in Trois Sauts, which takes two days by boat to get to.

Medics who are interested in doing an overseas stint in French Guiana often receive notices of available positions through the mailing lists or ortanizations like Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, according to the ground coordinator Dr Paul Brousse.

Doctors sometimes stay as little as three months so the turnover of medical staff can be high. Local doctors and nurses do not want to take up the positions located inland. Sometimes there is a lack of staff but efforts are made to minimize these occasions as clinics like the one Rombauts works at are the only place where people from a large catchment area can get treatment. Aside from the unique personal experience of living in Amazonia, a major selling point for foreign doctors is the diverse and new professional experience they gain.