One study estimates the world of work is changing ten times faster than the first industrial revolution and with three thousand times the impact. So, what can we expect to see in coming years?

Traditional 9-to-5 working patterns and the idea of a job for life could be things of the past.

The digital economy means our work lives have changed so much that they’re almost unrecognisable from a few years ago.

One study estimates the world of work is changing ten times faster than the first industrial revolution and with three thousand times the impact.

So, what can we expect to see in coming years?

- Robots could eliminate more than 5 million jobs in 15 of the world’s major economies.

- In Europe, between 40 and 60 percent of jobs are expected to be automated.

- The highest risks are faced by Southern Europeans.

- 2 out of 5 employers in the G-20 countries say they cannot find qualified people for the jobs they have.

- In Europe, it could mean 825,000 unfilled vacancies by 2020.

- The evolution of automation also means we could soon have between 15 and 20 different jobs in a lifetime.

Wages vs Productivity

Real Economy went to The Brussels Economic Forum where the debate was whether automation will lead to major productivity growth. But the question many people want an answer to is whether people will be better off.

Could the introduction of automation mean a stagnation in wage growth, as it did in Germany, or perhaps even a reduction in salaries?

President of the Foundation on Economic Trends, Jeremy Rifkin, told Euronews what might happen.

“If you have a technology set up you will pretty much know whether the goodies will go upstairs or down to the people. For example, the first and second industrial revolution infrastructures in the 19th and 20th centuries were designed to be centralised top-down; you had to make the scale vertical in order to get returns to your stockholders; and you had to have big global companies. And whether you were in the Soviet Union or in Europe you had to do it the same way.

“What’s interesting about the third industrial revolution is that it’s designed to be distributed not centralised. So, you can try to control it and monopolize it. Governments can try to do it. There are already some Internet companies like Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Amazon who may try to control it but if you try to control it you lose the productivity. That is because you can close it but you won’t have the network effect of having everybody engaged together.”

However, not all companies think the same way. Euronews asked Pierre-Dimitri Gore-Coty, Head of EMEA, Uber, whether companies in the digital space will see wages start to increase at the bottom so that the inequality gap will start to close.

Healthy competition

“I don’t think that Uber and apps like Uber are honestly the ones controlling the earnings,” Mr Gore-Coty said.

“At the end of the day, we are a platform and people are free to connect to it. However, we do monitor earnings very quickly and we know that this is one of the things that drivers, for instance, care about most. And that means there is a pretty healthy competition across different tech companies and services to make it as attractive as it can be for people to join their apps.”

It is not a view shared by everyone though. General Secretary of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), Sharan Burrow, thinks some of the tech companies have become too powerful.

“Digitalisation is simply like the tram tracks of the future. So it does offer opportunities. You can see what’s happening now with the convergence of physical companies with big digital companies. You have Amazon, for example, which is buying up food companies, financial services, legal services: you name it. It’s already a global department store and it’s becoming too big to touch. First of all, it treats its workers like robots and the regulation is not actually cleaning that up.”

Some analysts say there is a risk of developing countries being left behind in the technology race.

Winnie Byanyima, Executive Director of Oxfam International, says that this must not be allowed to happen.

“What is most important is that governments find their role and use all the tools available to harness technology for the benefit of the majority and not just the few. We need to see governments investing in key areas of technological development as a way to maintain some public control.”

'Find a Robot'

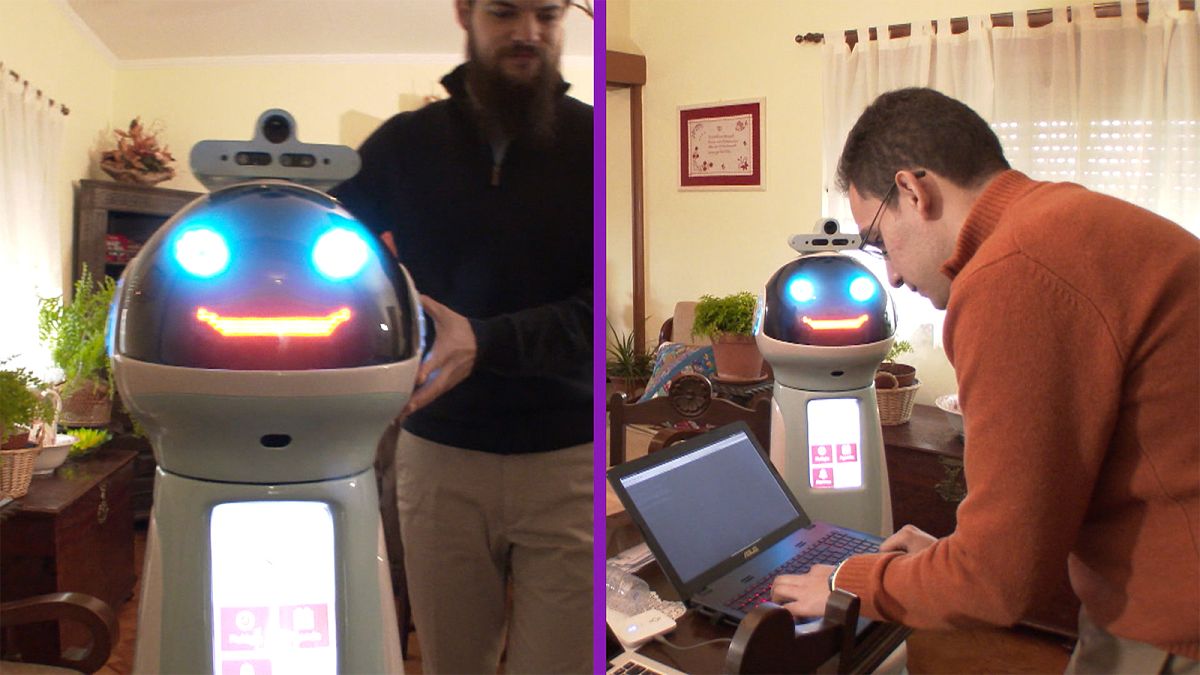

Prof. Robert Gordon from North Western University believes machines are a part of our daily lives, and that we work alongside them.

“We have robots now in manufacturing. We have a gradual introduction of robots in warehouses. We still have almost no robots in retailing, construction, utilities, healthcare and universities. There is a huge part of the economy where robots have just not been evident at all.

“I play a game called ‘find a robot’ in my daily life and I never see them in my local drugstore. You can check yourself out at a checkout kiosk with no human being, although there are humans there, watching to make sure you don’t steal anything.”

Over the past decade, automation in Europe has created a surge in jobs in the scientific, administrative and technical sectors. But the most job losses have been in construction and agriculture.

In the future, low-skilled workers are most at risk of losing their jobs, as their work comprises routine tasks which robots can often do more productively.

More skilled roles need creativity, expertise or people-management. These are social interactions that robots cannot replicate.

Their digital and soft skills will also help them access new jobs in healthcare and technology, which are expected to surge.

Or they may work in one of the 8% to 9% of new jobs that don’t yet exist but will do by 2030.

There is considerable speculation about what might need to change in terms of European regulation and in business models to create the jobs for the future.

Pierre-Dimitri Gore-Coty says there are two important changes that need to happen for the future of work:

“I think the portability of social benefits will mean we need to move from a world where benefits are tied to the employer, to a world where they are tied to the individual. This means that if I decide to drive a bit on Uber and do something else on another platform and maybe have a part-time job, I will still be able to accumulate all those benefits and keep them with me as I change course in my work life.

“The second important aspect is lifelong learning and figuring out ways for all of those people using apps like Uber to actually be prepared for the next jobs, wherever technology is taking us.”

Science jobs

Co-Founder & CEO of Transferwise, Kristo Käärmann, believes the next generation of workers should be better equipped for the changing world they will live in.

“The kids that are going to school today, going to University today, they should definitely look at science jobs, Käärmann says.

“They should look at learning how to code, learning how to build the new products in the future that automate some of these jobs we have today that are not necessarily creating a huge amount of value.”

Preparing for the future needs some serious planning.

Sharan Burrow stresses the importance of people and working conditions as the world of work evolves.

“What we need is, in fact, a new social contract. Some of the elements of the social contract have simply been diluted and need to be reaffirmed, such as a minimum living wage or a fair contract price.

“Social protection guarantees the right to bargain collectively. We are creating a society that is back to the future. Nobody wants their children and grandchildren to work in the conditions of the industrial revolution, and yet in many cases, such our current supply chains or in the new jobs across digital platforms, this is, in fact, the reality.”

Marco Buti, the Director General of Economic and Financial Affairs for the European Commission believes it is important to introduce new jobs and working practices carefully.

“It very much depends on the policies we implement in order to twist it in the right way. Policies have to be in place in order to allow a smooth transition from declining jobs and rising opportunities. It involves education, training, re-training, lifelong learning, reform of product and services markets, and not only labour markets. This is absolutely key.”

Jeremy Rifkin believes that, to a large extent, the future is already here and we are feeling its benefits and challenges.

“Technologies are never neutral and technological infrastructures are, through history, never neutral. They come with a price.”

“This takes us to a new form of globalisation, which we could call ‘glocalisation’. With this new infrastructure, communities in cities and regions are already able to virtually and physically engage each other all over the world. All you need is a cell phone.”

How do you see your working future?

Take part in our quick poll to find out what your working future holds in store for you.