For International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples, we look at how a community-led programme in the Maya Biosphere Reserve is revolutionising how we think about conservation.

In the heart of Central America’s most populated country, Guatemala, lies one of the most important spaces in the world for biodiversity: the Maya Biosphere Reserve.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

At over 21,000 km2, the reserve covers around a fifth of Guatemala’s total land and is the largest protected area in Central America. As the biggest tropical forest north of the Amazon, the park has a vital biological and cultural heritage, providing a home to countless endangered species and ancient Mayan archaeological sites dating back thousands of years.

The forest also serves as a critical carbon sink - a space which absorbs more carbon than it produces, an ecosystem essential to fighting the climate crisis.

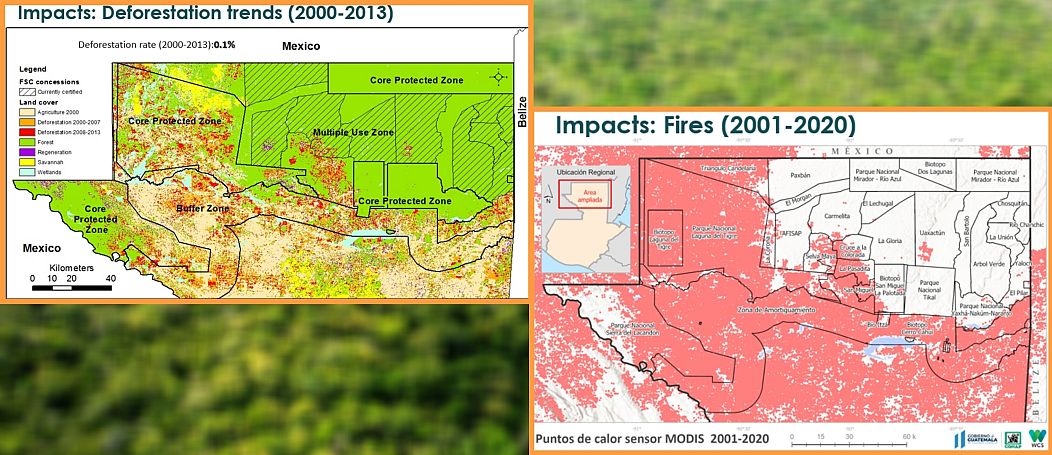

But the Maya Biosphere Reserve is as vulnerable as it is powerful. Its geographical positioning along a major drug smuggling route, has led to deforestation as narcotraffickers clear the forest to use as a landing zone on the journey from South America to Mexico and the USA. Illegal farming and logging has also posed a serious threat to the park, as people look to profit from the land. In the last 20 years, the reserve has shrunk in size by 8 per cent just from illegal cattle ranchers clearing the forest..

So why, in 1990, did the Guatemalan government grant 12 communities the right to farm and log in this critical space?

Indigenous and local communities as guardians of the forest

The idea was a concessions programme, where Indigenous and local communities were allowed to harvest the park’s natural resources - as long as any logging or farming was sustainable. All permitted economic activities were regulated and monitored by external groups like the Forest Stewardship Council.

These practices weren’t allowed throughout the entire reserve, which was (and continues to be) divided into several zones with different levels of protection. Human settlement, extraction of natural resources, and logging are explicitly banned in the core zones - which take up just over a third of the park. These are primarily made up of biotopes and national parks.

The buffer zones take up around a quarter of the reserve. These sit between the core zones and non-protected areas, and have little formal protection or monitoring. Their purpose is primarily to act as a barrier around the core zones. Finally, there are the multiple-use zones, which represent 40 per cent of the total park. This is where the concessions were allowed to take place.

Extraordinary as it may seem, thirty years on, the spaces which actively permit logging and farming are the areas with the lowest rate of deforestation. Since 2005, the multiple-use zones have maintained a near-zero deforestation rate. In comparison, the rate is twenty times higher in areas outside the community-managed concessions.

Where other parts of the reserve have buckled under considerable pressure from cattle ranching, narcotrafficking, and development - the zones managed by Indigenous and local groups have remained truly sustainable.

After over two decades of successful forest management, Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies dubbed the concessions model a “shining beacon of conservation.”

Given the recent issues with forest fires in California, the Amazon, and Australia - it’s also notable that the multiple-use zones in the reserve have the lowest incidents of fires. As well as protecting the land from illegal loggers and narcotraffickers, the communities who work in the reserve also help keep the forest free from infernos.

Opposition from NGOs, the military, and rebel alliances

It was a radical project, one which Greenpeace, Conservation International, and other local and international NGOs strongly opposed when it began.

But it wasn’t just conservation organisations who had an issue. Guatemala was entering the third decade of its brutal civil war, a situation which left the forest ripe for exploitation.

“Sometimes when we were working in the Maya Biosphere Reserve, in your way would be the army, or sometimes guerrillas,” explains José Román Carrera, now director of parks and development in Latin America for the Rainforest Alliance, who helped establish the reserve.

“The biggest threat during that time was the illegal logging allowed by the army, who were heavily involved, so sometimes we had to go and face the army - which was difficult! They had a lot of power and were intimidating, but we had to deal with that situation.”

On the other side, the team had to handle communities which were part of the guerrilla rebels, who felt they had a claim to the land and its natural resources. Carrera also faced personal threats, as one of the leading figures in the process.

“I received 82 death threats. Those were just the written ones. I also got many, many calls saying, ‘Leave the country or we’ll kill you, we’ll get your mother.’ I was shot at in my car—17 bullets. Another time they put a bomb at my house.

“But I’m still here! They tried to kill me and they didn’t. Eventually they realised I would never leave. I had to protect the Maya Biosphere Reserve.”

The Rainforest Alliance was one of the first international organisations to recognise the project’s potential. The NGO has been working with the communities in Guatemala - and Carrera - for over 20 years now.

Problems on the ground in the reserve look rather different these days. Narcotraffickers are more of an issue, but this is where the communities managing the land often come into effect. Carrera tells me of an occasion where drug smugglers landed a plane on a concession.

“The communities organised and realised they had to work with this situation and stop this from happening.

“It was difficult and some people died,” he explains, “but it means that the planes don’t land in these zones on purpose anymore.”

Good for man and nature

While the programme has resulted in the incredible ecological protection of the reserve, its economic benefits can’t be understated either.

Since its inception, the project has created nearly 9,000 jobs and generated more than €5m in annual revenue - creating a robust, local economy. Communities sell goods like honey and allspice, as well as timber products to customers around the world.

“People are living much, much better,” explains Carrera, “they have livelihoods, employment, education. They are working in an international market and doing international business by themselves, with peer support.

“And you speak with them and you see their faces - you see the success! And then you realise that there is no deforestation, no legal issues, the archaeological sites are protected, biodiversity is better,” he adds.

Global threats to the concessions model

Unsurprisingly, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused major financial problems for the communities involved in the programme. Due to a breakdown in global supply chains, they are facing an estimated €1.3 million loss in sustainable timber revenue and an additional €30,000 per week from the sale of palm fronds.

The other major threat to the reserve and the programme in general is perhaps a little less expected. An American archaeologist and anthropology professor, Richard Hansen, is fighting to create an ecological tourist centre in El Mirador, an ancient Mayan city in the forest.

Hansen wants to establish a US-funded, privately-managed park - completely with hotels, restaurants, and a mini railway for tourists. He’s spent a huge portion of his life dedicated to the forest, and argues that his development would protect the ruins and the reserve far better than anyone in Guatemala.

But Indigenous and local communities who live in the reserve, working every day to safeguard the forest, feel that this eco-tourist development would be a disaster for the reserve and its inhabitants.

At the time of writing this, over 200,000 people have signed a petition to stop the US government from supporting Hansen’s pipedream - arguing that if he cared about conservation, he would support the forest concessions model - a tried and tested method.

This outpouring of support, along with recent public praise from Guatemala’s President Alejandro Giammattei, offers a beacon of hope to the communities at the heart of the programme. And rightly so, because after almost three decades of conservation success, the concessions model should be a blueprint we all look to learn from, rather than destroy.