COP27's host country is leading the way towards effective climate action by planting thousands of mangrove trees. But why are they important?

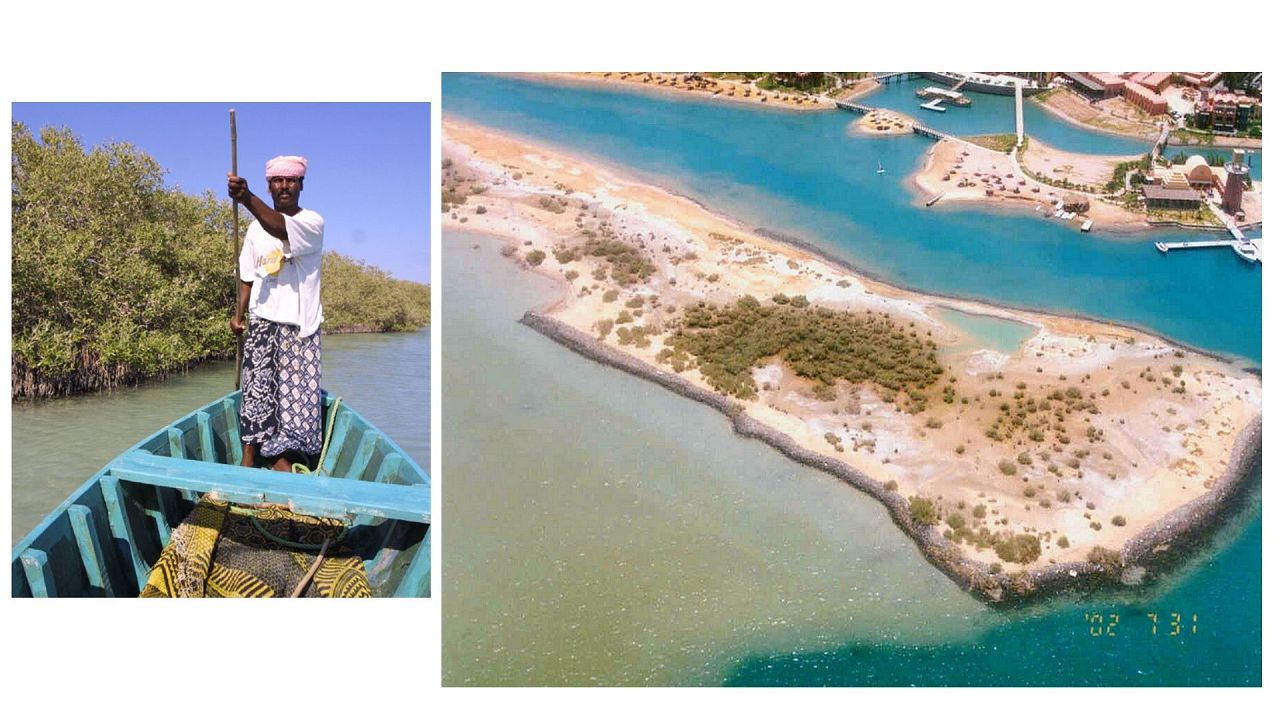

48-year-old Abu el-Hassan Saleh spent a lot of his childhood in his Red Sea home village of Al-Quweh, exploring the lush strips of mangroves that covered, at the time, swathes of Egypt’s expansive coastline.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

As a child, he played around his parents and grandparents as they grazed their camels on the trees, caught fish swimming between them, or cut them down to build fishing rafts.

Today, the fisherman says he had to leave his village and work in tourism instead, after a government project which he had hoped would restore the village’s dwindling fish population through regrowing its destroyed mangroves, failed to take off.

Al-Quweh was one of six Red Sea locations where a two-year government project aimed to rehabilitate mangrove plantations.

Launched in April 2020, the project was set to recover a total area of 210 hectares of mangrove forests. It was to serve as a line of defence, to slow down the effects of climate change - the most pressing of which is rising sea levels.

The rate of rise in Red Sea levels has nearly doubled in recent years, according to a 2021 study.

While this project failed to kickstart in some locations, it was a hit in others.

Why are mangroves so important?

Mangroves, nature’s defenders against beach erosion, used to grow naturally in 28 sites along Egypt’s Red Sea coasts. “Because of human intervention, their spread shrunk to around 500 metres only at each location,” says Dr Oman Ghali, head of the Environmental Plants and Dry-land Cultivation Unit at the government’s Desert Research Centre.

Mangrove trees grow in the saline waters of these regions to help stabilise soil and protect beaches from erosion during fluctuating tides through their intertwined roots that clamp the ground together.

The deterioration of Egypt’s mangroves is the result of the mushrooming construction of tourist villages nearby mangrove forests.

This is as well as recurring oil leaks from shipping lines and oil excavations, and locals’ continuous overgrazing of their herds of camels, goats and sheep, explains Dr. Sayed Bakr, director of the Western Desert Reserve.

So the ongoing project - with a budget of 4 million Egyptian pounds (€200,054) and funded by the government’s Academy of Scientific Research and Technology - should “increase mangroves’ spread to 60 acres in each location”.

It aims to address the risks of climate change, including sea level rise and carbon dioxide absorption, and maximise the economic potential of these locations through honey bee projects. This would transform the mangroves into tourist attractions.

Mangroves are also considered shelters for small fish, Dr Ghali notes. And the forests are immense absorbers of carbon emissions. According to a 2020 study, an acre of growing mangrove trees can absorb between 50 to 220 metric tons of carbon - this is three or four times the amount absorbed by regular forests.

How are mangrove trees planted?

Ragab Senousi, an engineer working on the project, says that the multi-stage process of planting mangroves requires 10 workers at each site.

The planting process takes place from April to October every year. Specifically-prepared greenhouses are set up, lined with soil-filled basins in which seeds collected from the naturally-grown mangroves are planted.

Mangrove seedlings then take six months to grow, and these are then replanted in several locations.

Elshazly, a man assisting on the project in Safaga, has already witnessed the benefits in his own life.

Aside from the income this temporary tree-planting job has provided, he has gained a huge amount of knowledge as a fisherman, he says.

“Fish have increased in my area, and marine species that have disappeared due to mangrove degradation have reappeared.”

Mangroves are perfect locations for making honey

Another advantage to local communities near mangrove sites is the honey bee apiaries set up in these locations.

Mahmous Abbas, a professor in plant protection at Egypt’s South Valley University, travels 761 kilometres every 15 days between Qena - where he’s based along the Nile - and Safaga, to supervise the honey bee apiaries inside the growing mangrove forests.

Describing mangrove honey as one of the best types of honey, Professor Abbas says the reason is that “bees feed on completely natural nutrition, from the nectars of the two types of mangroves that naturally grow in Egypt, without any industrial intervention.”

He notes that the method of pollination in mangrove forests is specific to this type of plant, as the nectar is left directly on the leaves, rather than the flowers.

In addition to its sweet taste, “mangrove honey is a cure for respiratory diseases, blood pressure, rheumatism and is a remedy for sore throats,” too.

Over six months, Professor Abbas produced 200 kilos of mangrove honey as part of a trial. He says one kilo of honey is sold for 200 to 300 Egyptian pounds (between €10 and €15).

But to Abu el-Hassan Saleh of Al-Quwih, these financial opportunities never made it to his village as was planned, as the project was hit by security and logistical challenges.

Bureaucracy gets in the way of progress

Dr Ghali says they were only able to do the project in three locations: Safaga, Hamara and Al-Qala’n, and only managed to grow 50,000 trees each year - a third of the 300,000 seedlings they aimed to grow.

One key obstacle, he says, was obtaining the required security, which “takes years”.

“We are trying to benefit our country, and are instead being held back by restrictive bureaucracy that makes us think a hundred times before working on such projects again,” he laments, adding that, had the approvals been easily granted, it would take only five years to plant five million seedlings to cover all 28 sites.

Financial challenges are also present, but could be dealt with if permits are facilitated, as “funders are keen on the project”.

For those working on the ground, logistical challenges are also daunting. Sennousi and Professor Abbas, whose frequent commutes span up to 400 kilometres between far away locations, say that lack of transportation is a key hurdle.

Referring to COP27 - which Egypt is due to host in November - Dr Ghali is calling on local authorities to help workers with this project.

“It would help to show attendees that Egypt prioritises environmental and climate projects,” he concludes.