Coral biologist Megan Clampitt tells us all about her job protecting the Indian ocean’s vital coral reefs.

Could you imagine what it would be like to live and work on a paradise island in the Maldives? A place where your shoes won't be deemed necessary as the only surfaces your feet will ever touch are the silky ivory white sands of its paradise beaches. Or the fresh turquoise waters inviting you for a dive as you jump off the boat - your main mode of commute.

No shops or busy streets to distract you. Velaa is a 400 x 400 sq m private island, hosting a 5-star luxury resort, located in the gorgeous Noonu Atoll. Your main occupation? Diving into the ocean everyday to restore precious corals. This is Chicago-born coral biologist Megan Clampitt's daily life since she relocated from Nice, France, to this private island in the Maldives.

She first embarked on a four month solo backpacking journey. Whilst travelling, she had the opportunity to dive around Australia’s Great Barrier Reef and learn about the state of the oceans firsthand. This is when she fell in love with diving and decided she wanted to play a role in the conservation and restoration of marine life.

During a skype interview (they do have wifi) she described her slow-paced low key lifestyle, and the importance of coral protection for the health of our environment.

Growing new corals and putting them back out onto the reef

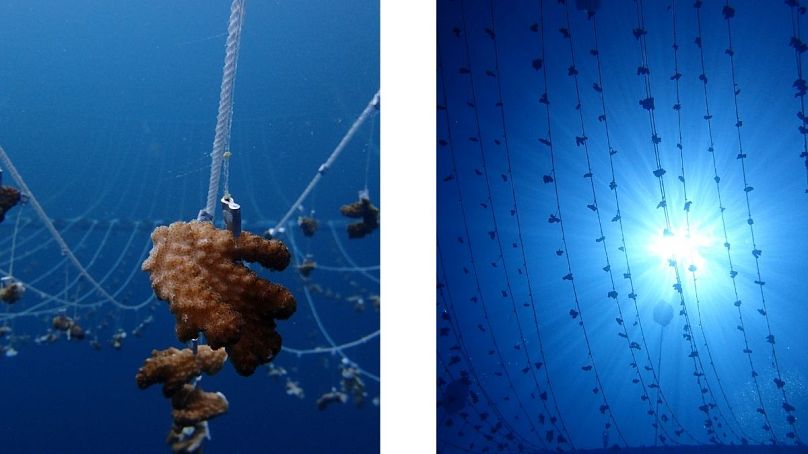

In a similar fashion that a gardener would take care of a patch of vegetables, Megan Clampitt and her team dive 2 to 3 times each day to grow underwater corals in so-called 'coral nurseries'. A fragment piece of coral is taken from a big donor colony, put on ropes into a nursery, and with the right conditions, will continue to grow as it can reproduce asexually.

“By taking these fragments and moving them to a nursery setting, we are helping them have the best chance for survival. This is done by giving them good access to light (they have a symbiotic relationship with an algae that lives in their cells that does photosynthesis and provides them with the majority of their food), keeping them away from predators, lifting them off the bottom to keep them away from sedimentation and from recreational activities, and placing them where there’s good water flow,” she explains. Due to the topography of the island and the conditions the corals face, placing them on mid-water floating rope nurseries is the best methodology.

Once the corals are around 10 cm wide and strong enough to survive in the big wide ocean world, they’re moved onto the reef and monitored every three months. The whole operation takes from 9 to 12 months to complete. “A lot of reefs are degraded and coral populations are small. By growing corals in nursery settings we can increase their numbers on the reef as they grow faster in these specific settings,” she explains. Most of her time, in fact, is spent getting the corals ready for the reef.

Coral reefs provide shelter and food for the local fish population. However, to prevent changing their habitat too abruptly, Clampitt hangs the ropes of corals for a couple of days before transplanting them officially. An abundance of fish then quickly gravitate towards the newly settled corals: “you really do see the fish coming to have a look at the reef, and see what’s going on,” she describes. Amongst new homeowners, she counts clown fish, crabs, parrot fish, eels, butterfly fish, angel fish, black tip and white tip sharks and occasionally octopuses, proof of the area's biodiversity clear improvement.

Megan Clampitt spends most of her daytime in water. Scuba-diving for 1 to 2 hours each time means she is pretty much fully dedicated to her job and nothing else. “People don’t realise how small islands are, how remote it can be" she says. "When you are living on an island, you can’t get everything you want, which means you have to accept that life itself is different in that sense. It’s simpler, life’s slower.” she says.

Living on a paradise island also means that if your phone breaks, there’s nowhere you can go to get it fixed. Or that if you run out of your favourite food, you’ll need to wait until there’s a shopping trip arranged to take you by boat to a local island. When Megan Clampitt isn’t diving you’ll find her playing cards with her team or enjoying organised film nights.

Coral bleaching

More than 60 per cent of coral reefs in the Maldives were affected by 'bleaching' in 2016 reports the Guardian, due to extreme changes in ocean temperatures. The Australian Marine Conservation Society describes ‘bleaching’ as a loss of colour due to the expelling of algae, “the stunning colours in corals come from a marine algae called zooxanthellae, which live inside their tissues. This algae provides the corals with an easy food supply thanks to photosynthesis, which gives the corals energy, allowing them to grow and reproduce. When corals get stressed, from things such as heat or pollution, they react by expelling this algae, leaving a ghostly, transparent skeleton behind.”

Less coral simply means less fish. Climate change, deep-sea, mining plastic pollution and overfishing are currently harming the ocean and every level of the ecosystem, warns Greenpeace.

So far, Megan Clampitt and her team have managed to transplant 3000 pieces of healthy corals onto the reef with a survival rate of approximately 80 per cent. The project, which is privately funded by the owner of Velaa Private Island who has a passion for the Maldives and restoration of the reef, has been a huge success. The coral restoration team has witnessed a coral cover increase from 10 per cent to almost 17 per cent and have noted an increase in fish species.

“Overall, since the project has been in place, we are seeing more coral and more fish on our house reef which is exactly what we were hoping for. I have been working on the project for the past 9 months, but it has been in place for about three years now,” she concludes.

Related | These holiday destinations need your help cleaning the beaches