Once overlooked, the region around Alexandroupolis is now at the centre of plans to secure gas supplies and reshape the EU’s energy map.

Thrace, at the southeastern edge of Europe, has for decades been a “forgotten frontier” in the European narrative, far from the centres of decision-making and investment.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Today, however, that picture is changing rapidly. The region is being reshaped into a critical geopolitical and energy hub as Europe accelerates its decoupling from Russian energy and looks for new, secure gas gateways.

Thrace — and Alexandroupolis in particular — is now at the heart of this redesign, taking on a growing role in the EU’s energy diversification.

From a “forgotten border”, the region has evolved into a strategic crossroads for European energy security.

Why gas is still necessary

As Europe prepares to say goodbye to Russian energy for good, with Russian oil and gas imports set to reach zero by 2028, a fierce debate is unfolding in European capitals about how to secure the next phase of the energy supply for European Union households and businesses.

Despite years of efforts to accelerate the green transition, natural gas — the cleanest of the fossil fuels — is expected to remain a critical part of Europe’s energy mix for years to come, acting as a bridge fuel.

According to analyses by the European Commission and international energy organisations, natural gas continues to play a key role in keeping electricity grids stable, balancing renewable energy production, and supporting industrial energy security.

The interruption of Russian flows, combined with a gradual recovery in demand, creates a significant gap in the European market.

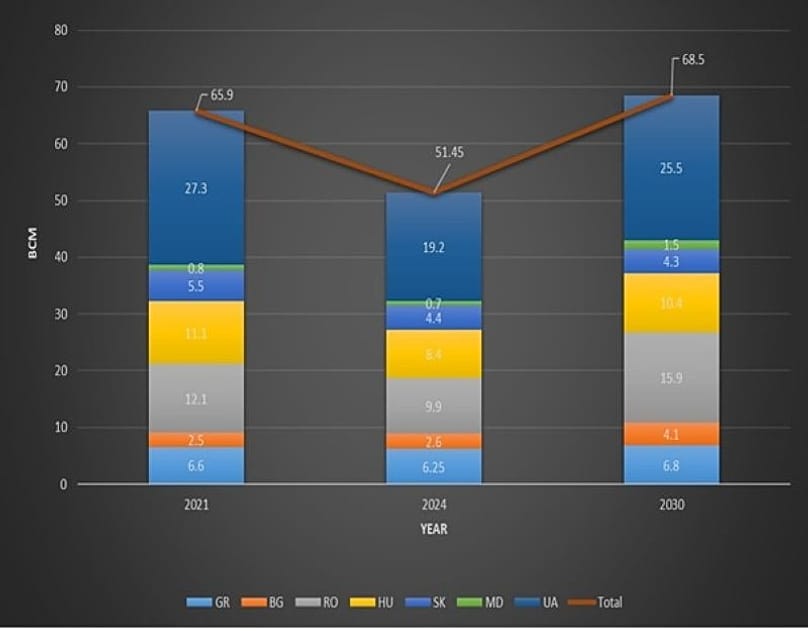

By 2030, it is estimated that central and eastern Europe will need an additional 35 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas per year, which will have to be covered through new infrastructure, diversified supplies, and alternative routes.

Countries that manage to fill this gap are expected to benefit in two ways: through revenues from transit and gas trading, and through increased geopolitical influence as key pillars of Europe’s energy diversification strategy.

Greece’s battle and the decisive role of Thrace

As Russia’s energy squeeze has left many pipelines running through Europe underused, liquefied natural gas (LNG) is emerging as the key alternative to meet European demand.

In this market, Greece is seeking to secure a substantial share, leveraging its geographical location and its existing — and expanding — infrastructure.

Central to this strategy is the so-called Vertical Corridor, the pipeline network linking the country’s two LNG terminals — the FSRU (Floating Storage and Regasification Unit) in Alexandroupolis and the LNG terminal in Revithoussa — with the interconnected gas systems of Bulgaria and Romania, allowing volumes to be transported as far as Ukraine.

The same corridor can supply markets in Hungary, Slovakia, and Moldova, strengthening energy security in central and eastern Europe.

At the same time, discussions are underway to further expand the pipeline network so that LNG, largely of US origin, can enter Greece and be channelled to even more European markets, among them Italy via TAP, as well as Austria, turning the country into a key gateway to the EU.

To support this ambition, Greece plans to build a second floating FSRU terminal or a floating LNG storage and regasification unit.

One of the companies moving in this direction is Gastrade, which operates the Alexandroupolis FSRU.

The company has already received environmental approval from the Greek state for the installation of a second unit, close to the one already in operation.

This FSRU will be named FSRU Thrace and will be located in the same sea area as the Alexandroupolis FSRU.

However, the project comes with significant financial challenges. Construction costs are estimated at close to €600mn — an amount that, according to the project’s management, cannot be secured without support from European financial instruments or state funds.

Hard poker in Brussels

A high-stakes political and economic game is currently being played in Brussels over the future of gas infrastructure in Europe.

In recent years, the European Commission has taken a strong stance on phasing out the financing of gas projects, arguing they are inconsistent with the green transition and climate neutrality goals.

This position is challenged by industry players and national governments, who insist gas will remain necessary for many years to come.

Negotiations are ongoing and Brussels is under growing pressure to shift its stance and allow financing for gas infrastructure.

“It is not only Greece that is asking for this. Romania, for example, is developing a new gas field, Neptune Deep, and wants to have the option to sell the volumes on the European market,” Greek energy industry players told Euronews.

The role of the Americans

At a time when the European Commission is under increasing pressure to reconsider its approach to gas, the United States is moving faster.

Major US financial institutions, such as EXIM and the US International Development Finance Corporation, have expressed an interest in helping finance the construction of a second floating FSRU terminal in Alexandroupolis, viewing the project as an opportunity to boost US LNG exports to Europe via the Vertical Corridor.

This issue will be the focus of a special meeting planned by the US Department of Energy in Washington in late February aimed at strengthening the Vertical Corridor.

The meeting will be attended by energy ministers and industry representatives from central and eastern European countries.

“The Washington meeting will be attended by a delegation from the European Energy Commission, led by EU energy director general Ditte Juul Jørgensen,” said Kostis Sifneos, vice president of Gastrade.

He added that financing for Vertical Corridor projects would be high on the agenda, as debate in Brussels over funding gas infrastructure has intensified in the context of Europe’s decision to decouple from Russia’s gas.

“Countries such as Ukraine, Hungary and Slovakia will need European support for infrastructure projects to replace Russian gas. We expect this discussion to conclude in 2026 and to deliver a positive result,” Sifneos said.

At a time when energy security is at the core of European policy, projects such as the Alexandroupolis FSRU floating facilities will be a testing ground for a more realistic European energy planning.

All eyes now turn to Brussels, which is called upon in 2026 to decide under what conditions and with what geographic strategy gas will continue to flow into the European market.