Newly released DOJ and congressional records show Jeffrey Epstein received real-time insight into UK tax and Bank of England policy discussions via Peter Mandelson, raising stark questions about how private networks intersect with public governance.

The newly published tranche of court documents published by Congress and the US Department of Justice after a transparency push on Capitol Hill has rattled reputations on both sides of the Atlantic.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

They range from revealing Microsoft founder Bill Gates' alleged extramarital affairs, to emails featuring former Secretary General of Council of Europe Thorbjørn Jagland discussing "extraordinary girls" he was introduced to.

Among the most sensitive strands for economic and policy watchers are the exchanges involving Peter Mandelson, who held top positions in the UK as a towering figure in the Labour party for decades, including Secretary of State for Trade and Industry in 1998 and Secretary of State for Business and Innovation.

He also served as European Commissioner for Trade in Brussels in 2004 when the UK was still part of the European Union.

On Tuesday, the speaker of the upper chamber of parliament confirmed that Mandelson resigned from his position in the House of Lords.

The British government said earlier Tuesday it had sent a file of material to police looking into allegations Mandelson passed sensitive government information to late financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer told his Cabinet that he was “appalled” by the revelations in newly released Epstein files, and was concerned there are more details still to emerge.

Is it illegal?

It remains unclear whether the published Epstein material contains a smoking gun that could lead to criminal liability for Mandelson or merely a paper trail of ill-advised proximity.

The emails indicate a very close relationship between the two, with warm accolades being exchanged, like a 50th birthday greeting saying "Wherever he is in the world, he remains my best pal... Jeffrey, we love you."

The files depict a long-running relationship in which Epstein was not merely a social acquaintance but also an interlocutor on personal financial matters and, perhaps most shockingly, on UK government policy.

Bank records reproduced in the released material show three separate payments totalling $75,000 (€63,575) wired to accounts connected to Mandelson between 2003 and 2004.

Separately, in 2009–2010, Epstein appears to have wired funds — including £10,000 (around €12,000) to support an osteopathy course for Mandelson’s husband — after Epstein’s release from prison.

Mandelson has said that he does not remember receiving the money and will investigate whether the documents are authentic.

But he resigned from the governing Labour party on Sunday, saying he did not want to cause the party “further embarrassment”.

These transactions complicate the narrative of a purely social relationship because they took place while Mandelson was a senior public figure and often at moments of intense market and regulatory debate.

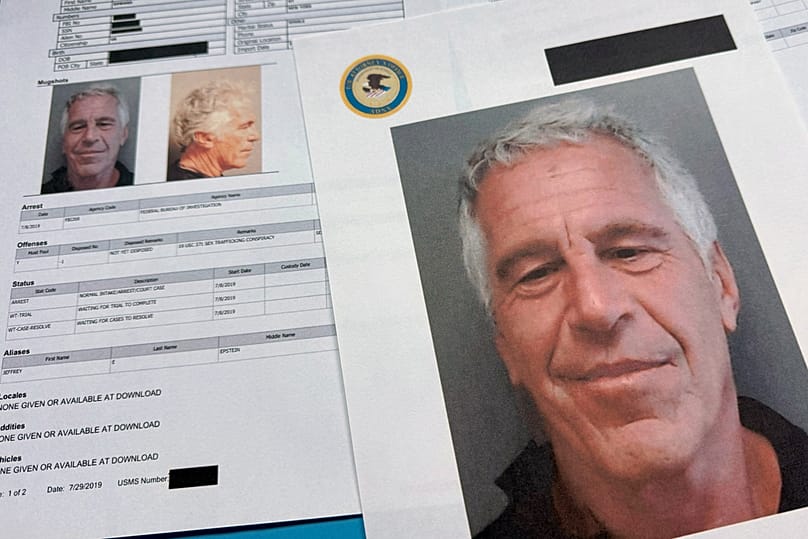

Epstein was first indicted on sex trafficking charges in 2006 and pleaded guilty in 2008, a timeline that overlaps with Mandelson's interactions about personal issues.

Consistent reporting on the Epstein case has shown that many of his closest friends and associates were likely aware of his activities much earlier than when the formal charges were made.

Advance notice on EU policy

From a business and economic policy perspective, the Epstein files involving Mandelson raise questions about the permeability of policy processes to private entreaties and interests.

According to the files, an internal memo relating to EU rescue financing — a planned €500 billion facility to support struggling member states — was forwarded to Epstein in May 2010 with Mandelson suggesting in an email that “it should be announced tonight”.

That exchange sits awkwardly against Mandelson’s record as European Commissioner for Trade from 2004 to 2008, during which he negotiated on trade access, rules for transatlantic commerce and protections for key industries.

At the Commission, trade policy and economic governance require strict confidentiality and coordination among members and partners — laxity with sensitive drafts, even in private correspondence, undercuts core diplomatic and economic protocols.

This email, dated just before an official announcement, indicates that Epstein had advance access to market-sensitive data central to the European Central Bank’s crisis-era strategy.

Acting against his own government?

At the height of the post-crisis regulatory push, Mandelson was discussing the design of the UK’s bankers’ bonus tax directly with Epstein.

The policy was one of the Labour government’s flagship responses to public anger at bank bailouts — an immensely sensitive issue, considering how much average citizens were affected by the 2008-2009 financial crisis, and their resentment that the bankers who had caused it were being "helped" by governments on both sides of the Atlantic.

The bankers’ bonus tax was designed as a one-off levy to discourage large, immediate payouts as a signal of restraint after banks received state support.

The details mattered: if the tax hit only cash, banks could keep rewarding executives as much as before by shifting bonuses into shares or payments pushed into the future, dulling the sting for bankers while preserving the crowd-pleasing headline.

If it covered deferred and share-based awards too, it would be harder to sidestep because it would bite on the whole package, not just the cash paid that year.

And its scope was closely watched by markets.

“[A]ny real chance of making the tax only on the cash portion of the bankers bonus[?]”

That question, sent by Epstein in December 2009, is followed minutes later by Mandelson’s reply, which acknowledges both the pressure and the internal resistance.

“Trying hard to amend as I explained to Jes last night. Treasury digging in but I am on case.”

Mandelson identifies the Treasury as the obstacle, suggests he is actively seeking changes, and keeps Epstein apprised in real time.

In subsequent messages, Epstein asks to be informed in advance of developments — “let me know before jes please,” — and Mandelson replies with a single word: “Treasury”.

In later correspondence cited in the file set, Mandelson is described as advising Epstein that JPMorgan’s chief executive should “mildly threaten” Chancellor Alistair Darling.

Taken together, the messages show a private channel into the mechanics of tax policy at a moment when regulatory policy was an important market variable.

Bank of England and internal notes

A separate chain from August 2009 places Epstein inside discussions touching directly on Bank of England strategy during the credit crunch.

An internal note sent to the prime minister’s office and then forwarded to Epstein sets out concerns that quantitative easing alone would not restore lending.

“Bank’s QE focus on buying gilts is fine — but they have not done enough credit easing in the Fed sense,” Epstein remarked. “Lack of securitisation market will be a real drag on that for years to come”

Mandelson forwards the note to Epstein with a brief gloss: “Interesting note that’s gone to the PM.”

Quantitative easing or QE is the central bank’s emergency tool for pushing money into the system. The Bank of England creates reserves and uses them to buy assets in —Britain’s case, mainly government bonds or gilts — with the aim of lowering borrowing costs and encouraging lending and investment.

Epstein’s response homes in on the practical implications, asking: “[W]hat salable [sic] assets?”

The reply — “Land, property I guess” — appears to acknowledge that asset disposals were being contemplated as part of the broader crisis response.

While the emails do not amount to trading instructions, they do show a private individual being looped into live thinking on quantitative easing and state asset sales — subjects where timing and expectation matter.

In Westminster, senior figures have called for inquiry and why commentators have observed that the scandal reveals not just Mandelson's personal failings but institutional vulnerabilities.