France is electing its next president this month. Experts say the position has an unprecedented amount of power. Why is that?

Before taking the reins as head of state, Emmanuel Macron suggested France needed a “Jupiterian” president, saying that a “normal” person would be destabilising.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The comparison of a democratically-elected position to the King of all Gods in Roman mythology may seem hypocritical in a country that violently overran its monarchy centuries ago.

Yet in the last 50 years, France’s constitution has evolved, with more power consolidated in the president.

“We have a president in France who presides over the Republic, who controls the government, who controls parliament, who controls the Constitutional Court. It makes a super president, like Jupiter, as we call Macron,” said Christophe Chabrot, a senior lecturer in public law at the Lumiere University Lyon 2.

“It’s a little bit as if we returned to 1830 when in European monarchies the king was beginning to lose his powers to the prime minister but still retained a lot of power,” Chabrot added.

Critics say France’s parliament is becoming a rubber stamp that approves the president’s bidding, with some politicians calling for a new constitution that brings more balance to the institutions.

“The President of the Republic in France has by law, much more power than any other president in Europe,” said Delphine Dulong, a political science professor at the University of Paris I, Pantheon Sorbonne.

“And in practice, successive presidents have also made very broad, very extensive use of their constitutional rights.”

The beginnings of France’s Fifth Republic

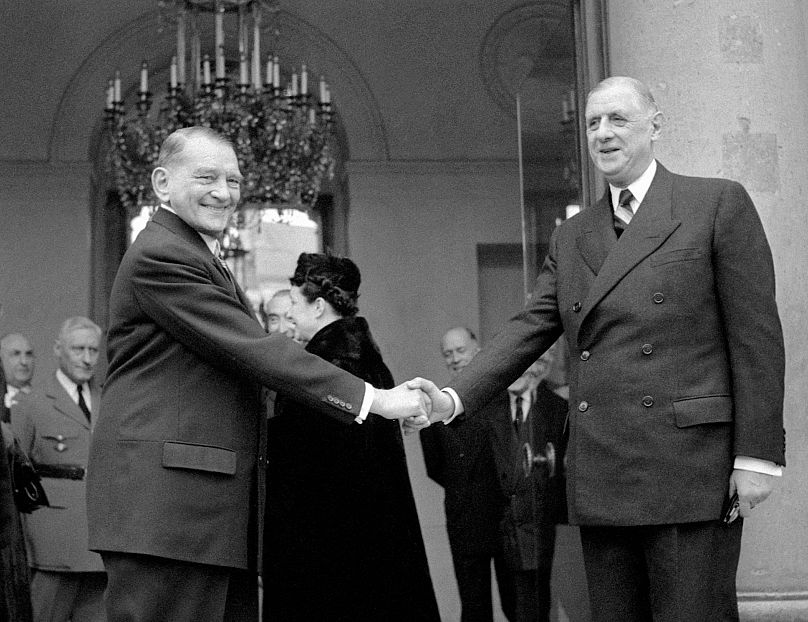

France’s current constitution dates back to 1958 when renowned General Charles de Gaulle formed a new republic following an uprising in Algeria.

President René Coty said France was on the verge of civil war amid the riots and that he would designate the “most illustrious of the French…who, in the darkest years of our history, was our leader” to lead the government.

Later that year, de Gaulle was elected by politicians as the first president of the new Fifth Republic.

The previous republic dated back to the end of World War II and gave more power to the parliament, creating instability and competition between political parties, experts say.

The vision of de Gaulle for the new republic was mainly to reinforce the powers of the executive.

“De Gaulle wanted a president that was not limited,” said Dulong. “In de Gaulle’s mind, the president was above political parties and had to be politically neutral.”

It’s the changes that followed that would both reinforce and stray from that original vision, creating the presidential regime in place today.

Universal suffrage

One of the major changes that contributed to the current French presidency was the 1962 constitutional referendum.

In an effort to reinforce his legitimacy as president, de Gaulle held a referendum on how the president is elected.

The population supported the referendum, voting 62% in favour of electing the president themselves rather than politicians.

The move both reinforced the power and legitimacy of the president while also politicising the role, experts say.

“(The president becomes) necessarily the leader or champion of a political camp. So there’s a politicisation of the presidential role,” said Dulong.

De Gaulle followed the move by dissolving parliament and holding new elections, regaining a majority.

Presidential term

A problem emerged called cohabitation, which was when the president and parliament came from opposing political parties.

Since the beginning of the Fifth Republic, cohabitation has occurred three times in 1986, 1993, and 1997.

The last time, right-wing President Jacques Chirac was forced to name socialist Lionel Jospin as his prime minister after calling snap elections.

Chirac then presented a law to change the constitution in 2000, limiting the presidential term to five years instead of seven. The question was put to the population in a referendum, with 73% voting in favour.

“The president embodies the general interest and the continuity of the republic. You will pick them more often. Your voice, your decision will matter more. Your democratic duty will be strengthened,” said Chirac.

The referendum meant that the presidential election would be held in tandem with the parliamentary election about a month apart, which assured that whoever won the presidency would win a parliamentary majority.

“You don't change your political opinion in a month. So the election of the legislature will often give the same majority as that of the president,” Chabrot said.

It’s held true for every president since, including Macron who won a majority in parliament a month after his election with a brand new political party and with MPs that were previously unknown to voters.

Could the system change?

Critics say that the system needs to change to rebalance the institutions so it’s not one person making all of the big decisions without being held accountable for them.

“We saw very recently in France that it was mainly the president, supported by a council, who made the decisions during the pandemic,” said Dulong.

“But since the president can’t be attacked, it’s Prime Minister Edouard Philippe who is being brought by some before the courts.”

Far-left presidential candidate Jean-Luc Melenchon is among those calling for a Sixth Republic to “abolish the presidential monarchy” in a new constitution.

But Chabrot at the University of Lyon says that eliminating Article 9 of the constitution, which designates the president as head of the council of ministers, or cabinet, could also add balance to the system.

Another change could be scrapping the presidential election so that the president is elected by MPs, senators and local councillors as was originally written in the 1958 constitution.

“Everyone says the French are attached to the presidential election, that it’s a democratic right that you can't go back on. That remains to be seen,” said Dulong.

“When we look at the abstention rate and blank ballots since the 1980s, we see that the presidential election is an election that is in crisis,” she added.

A lot of the changes that led to the current system received the support of the population, with de Gaulle consolidating his power through referendums.

“Every time the president pressed a button he won. De Gaulle in 1962, for example, pressed the referendum button and won. He pressed the dissolution of parliament button and won. So, each time, the French president reinforced his own power,” Chabrot said.

For now, voters will head to the polls in April to pick their next president.