Voters will be busy in Serbia this Sunday with presidential, parliamentary and regional elections planned.

Serbia will choose its next president on Sunday, 3 April, during a busy day of democracy that will also see MPs and regional assemblies elected.

Who is running to be Serbia's next president?

Incumbent Aleksandar Vucic has been the dominating political figure since his Serbian Progressive Party managed to form the government after presidential and parliamentary elections in 2012.

He quickly seized the opportunity to reshuffle his party, marginalise political opponents both inside and outside the movement and propel himself from the position of defence minister to prime minister and the president.

Vucic's critics find it difficult to forget he was information minister in the government of Slobodan Milosevic -- accused of genocide and war crimes but who died while awaiting trial -- and deputy chairman of the Serbian Radical Party, known for its ultra-nationalist rhetoric during the wars in former Yugoslavia.

Although he distanced himself from his political past, adopted a pro-European orientation, oversaw Serbia’s accession negotiations with the EU, created good ties with Western politicians -- notably Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron -- and made reconciliatory moves in the region, he has often been branded an autocrat and populist because of his uncompromising handling of political opponents.

According to all the polls, he is the most popular politician in the country. This is why it is thought that the outcome of the presidential elections will be reflected in the parliamentary elections and, to a lesser extent, in the voting at the local level.

This is why, his critics say, he made the government resign and call early parliamentary elections to coincide with the presidential ones.

Who is in the race to try and unseat Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic?

Beyond Vucic, there are seven candidates vying to be Serbia's next president, four of whom come from the nationalist part of the political spectrum.

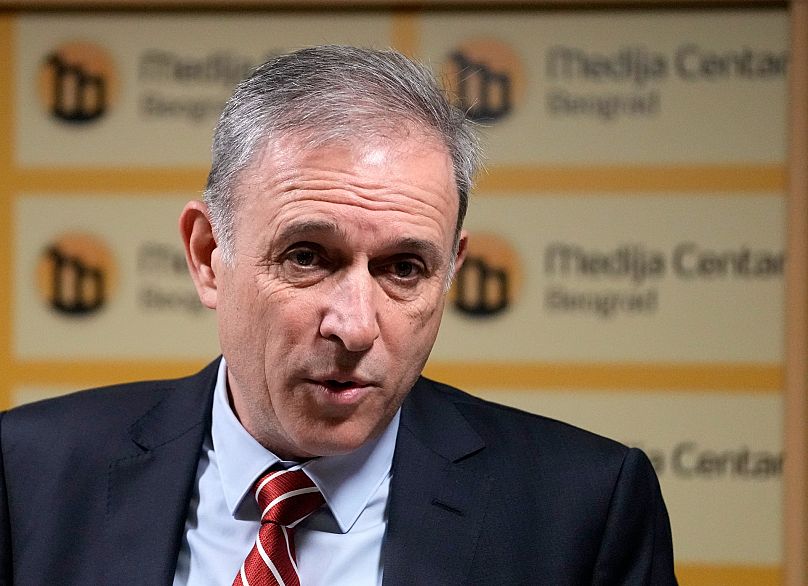

But perhaps the opposition candidate with the greatest chance of success is retired army general Zdravko Ponosh, according to opinion polls.

He represents a coalition of parties that consider themselves the successors of the civic and pro-European platform that saw Milosevic ousted in 2000.

Dominating that coalition is the Freedom and Justice Party, led by the former mayor of Belgrade Dragan Djilas. In the parliamentary elections, their list is called “Marinika Tepic – United for Victory”. Djilas and Vucic are considered to be political enemies.

How powerful is Serbia's president?

The constitution gives Serbia's prime minister the widest range of powers; the president makes the calls in areas of defence and foreign policy.

But, more often than not since the fall of communism, the president has been the most influential one because it was occupied by the leader of the strongest political party. This is the case now as well and is why presidential elections attract the most attention.

“Our opinion polls suggest that citizens are most informed that there are presidential elections," said Rasa Nedeljkov, programme director at the Serbian Center for Research, Transparency and Accountability. "The campaign is organised in such a way to prioritise presidential voting."

What about Serbia's parliamentary election?

There are 250 MPs in the country's single-chamber parliament, the People’s Assembly of Serbia.

At the last parliamentary poll -- held in 2020 amid the COVID pandemic -- the opposition boycotted saying there were no conditions for free and fair elections. They cited an "unfair political situation, pressure from the regime and a lack of access to the media".

The election saw a low turnout and Vucic's Serbian Progressive Party dominate. The party or its allies hold all but seven seats in the assembly.

This single-party parliament attracted criticism from Europe.

In order to avoid the same situation this time, negotiations were organised to try and improve the situation so that the opposition would participate.

The talks, which lasted for months, saw the opposition's access to public broadcasters increase and other conditions improved.

With the opposition agreeing to take part, voters will be able to choose from 19 parties or coalitions.

What issues are influencing the election campaigns?

The campaign of Vucic's ruling Serbian Progressive Party has tried to highlight the positive things that have happened since their ascend to power a decade ago.

It says up to 10 motorways or high-speed roads have been completed or under construction and that GDP growth (7.4%) last year was the highest in Europe.

The completion of the first high-speed railway in Serbia --which connects Belgrade and Novi Sad, Serbia's two largest cities, and will eventually go all the way to the Hungarian capital Budapest -- was set to coincide with the campaign.

The opposition accuses the government of corruption, claiming construction projects in Serbia are mainly money laundering schemes.

They say that the country is weakened by rigged and untransparent projects and partisan nepotism.

They focused on Vucic calling him the “head of organised crime pyramid in the country” thus effectively turning the presidential elections into a referendum on him.

The rule of law, the category for which Serbia got bad marks from the EU Commission and international watchdogs, was also at the centre of the campaign.

“We are not fighting for the ordinary, plain replacement of political structures," said Zoran Lutovac, leader of the opposition Democratic Party.

"Our state is a hostage, our children are fleeing the country. If we do not vote with our heads, our children will vote with their feet, running away to foreign countries.”

Vucic says the opposition is simply running a negative campaign to conceal the fact it has no plan of its own.

"They have this negative campaign every day," he said. "It has three tactics. One is to negate or oversee the achievements. They say that the hospital does not work and it does, it treats patients. Then they tarnish people, they say ‘you don’t have a degree, you are illiterate’. They couldn’t do that with me. It goes all the way to total dehumanisation of people, they say ‘he was born negative, he is psychopath, he deserves a bullet, he is a criminal, his brother is a criminal…that is a black campaign….But it won’t work, despite all the effort. Because the people see what’s been done and they want to have a future,”

Three months before the elections protests erupted over plans of mining company Rio Tinto to open a lithium mine in western Serbia. Protesters blocked highways and roads trying to force the government to stop the project as they feared water pollution and other degradation of the environment. Environmental activists and groups came into the spotlight damaging the government but also stealing potential votes from the opposition. The government managed to prevent environmental issues from determining the flow of the campaign by cancelling all the agreements with Rio Tinto and halting the project while embracing a green agenda.

War in Ukraine is a factor

When the war erupted, Serbia found itself between a rock and a hard place because of its decades-long policy of trying to join the EU while maintaining good ties with Russia and China. Many started to doubt the wisdom of its neutrality policy.

Vucic warned of pressure from the West, risks of losing energy supplies from Russia but still decided to maintain the policy of insisting that Serbia was not sitting on two chairs but rather on its own.

His government supported the UN declaration which condemned the Russian aggression against Ukraine.

He supported the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine but stopped short of imposing any kind of sanctions on Russia.

The panic over supplies of fuel and other goods was successfully preempted by bans on exports of key food products and putting a cap on prices.

The government tried to capitalise on Vucic's handling of the situation by painting him as being good at international crises and providing stability. His campaign's "Achievements speak for themselves" slogan was replaced with "Peace, stability, Vucic".

“The war in Ukraine played a very significant role because the campaign was completely overshadowed by it, especially in the first days of the Russian aggression," said Nedeljkov.

"But the political players quickly adjusted to the new situation and have even changed their slogans insisting on peace and stability.

"They had their hand on the pulse of the nation, which was clearly worried about their livelihoods with a real war in the neighbourhood.”

There was no major division between the ruling parties and the opposition on Ukraine. All parties favoured the neutrality of Serbia and the decision not to impose sanctions on Russia.

Voting from Kosovo controversy

Initially, Kosovo was not a big topic in the campaign. It emerged only after Kosovo Prime Minister Albin Kurti banned the organisation of voting for the Serbian election in the Serb-populated north of Kosovo and other Serbian enclaves.

Kosovo is a former province of Serbia and declared independence in 2008.

Belgrade and Russia have both refused to recognise it, in contrast to the United States and major European Union countries.

Voting had been allowed in the past, but Kurti said this time Serbia must be treated as any other foreign country, with voting taking place in embassies or consulates.

Serbia does not have an embassy in Kosovo. Instead, there is a liaison office, which is where Kurti wants ethnic Serbs to vote.

Serbia saw Kurti’s demand as acceptance that Belgrade de-facto recognises the independence of Kosovo while Kurti claimed that Serbian elections being held in Kosovo would be a breach of Kosovo’s sovereignty.

When are the results likely to emerge?

Polling venues close at 20.00 CEST on Sunday. The first results usually come from NGOs that observe the vote count. In previous elections, it was quite clear who won around 21:30. But the opposition boycotted these. This time around we may know the reliable - though not official - results sometime before midnight. The complete and detailed results will take around 24 hours.