Bulgaria has one of the lowest rates of vaccination in Europe and a huge problem with vaccine scepticism.

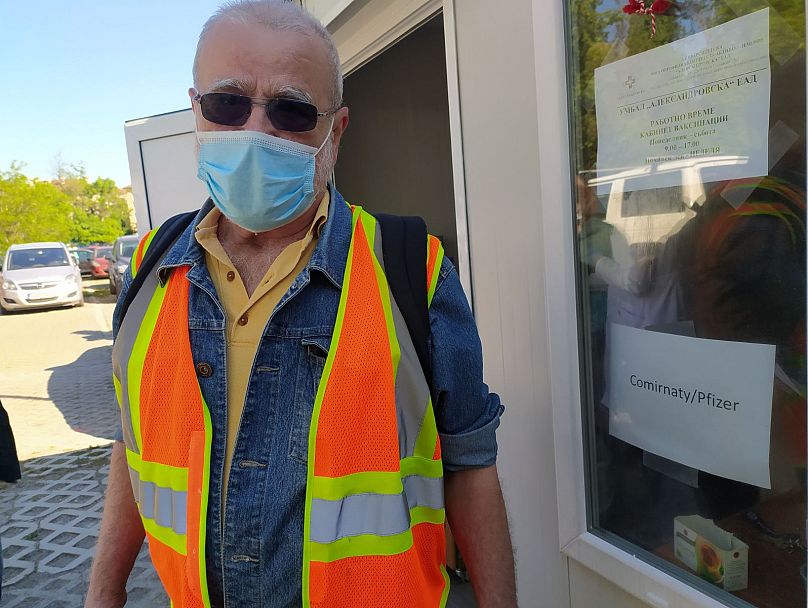

When Plamen Radomirsky, 68, had his first COVID vaccine dose in Canada early this year he was shocked to be told he’d have to wait two months for the second one. Keen to make sure he was 100% protected, he got on a plane for his native Bulgaria.

After ten minutes of queuing at a vaccination centre in Sofia, Radomirsky said, he had received his second dose.

“The rumours that elderly people have not been able to get vaccinated in Bulgaria are not true,” he told Euronews.

“As you see, it was fast, easy, and well organised. Canada's strategy is to immunise as many people as possible with the first dose and this lengthens the whole process,” he said.

The statistics, however, might suggest otherwise.

Only 6% of over-80s in Bulgaria have received both doses of the COVID-19 vaccine, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. It's around 10% in the 60-69 and 70-79 categories. The small Balkan country is one of the EU’s worst countries when it comes to vaccination rates, with just 13.5 % of the population immunised.

Much of the reason for that, experts say, is scepticism about vaccines, particularly amongst older, more conservative Bulgarians.

“Bulgarians are very conservative, and elderly people are even worse. Most are not educated and it is hard for them to understand the value of the vaccine,” said Tihomir Bezlov, an analyst at the Democracy Study Center in Sofia.

Bezlov, as a pro-vaccination activist, has tried to lead by example. He volunteered to be vaccinated with both Pfizer and AstraZeneca vaccines just to prove that it is efficient and safe.

A shortage of vaccines has also played a role - Bulgaria has only received one-fifth of the 500,000 doses of AstraZeneca it ordered in December 2020 - but Bezlov blames the government for not making the case for vaccination strongly enough.

This was particularly problematic in the run-up to Bulgaria’s elections in April, with politicians not willing to publicly back something that remains a divisive issue to voters.

“The lack of united solid political message for the profit with the vaccination gave this negative effect too,” Bezlov said.

The recent initiative of allowing “green corridors” at which anyone in any age group can get vaccinated is a step forward, he said, and had led to an uptick in vaccinations over the last month.

Losing faith

But in Bulgaria, even doctors struggle to persuade elderly people to get vaccinated.

”It is a hard job with uneducated people and even those who decide to get the dose don't come on their fixed day and time. Others get infected meanwhile and lose their faith,” Maria Vlahova, a general practitioner, told Euronews.

The process isn’t helped, she said, by serious shortcomings when it comes to the distribution and storage of vaccines.

Doctors receive 20 doses per day which have to be kept in coolers and are expected to collate and organise the appointments of those who want to be vaccinated.

They are expected to organise these vaccination drives in addition to treating regular patients and to keep those attending clinics for vaccination apart from those who are sick. In return, they receive a paltry f€5 for every two vaccinations that they administer.

Vlahova, a doctor for 42 years, is herself sceptical. Of her 2,000 patients, only seven have died from COVID-19, she said, a rate of just 0.35%. She, therefore, considers the pandemic less of a risk than heart attacks or cases of cancer. And her patients tend to agree.

“I, as a medical practitioner, have to protect my patients` interests, and I can not guarantee anybody they will not get worse or develop new diseases after the vaccination,” she said.

“Most of my patients are elderly people with many chronic illnesses. I did not read a statement from the pharmaceutical companies what side effects could be expected.”

She said that many of her patients ask her how it was possible for pharmaceutical companies to come up with vaccination for COVID-19 and not cancer.

It may be this scepticism on the part of doctors - as well as long waiting times - that explains why upwards of 1,000 Bulgarians per day are being vaccinated at green corridors rather than with their GPs. The government wants 70% of Bulgarians vaccinated by the end of the summer.

The dream was that a vaccination drive could have saved the country’s 2021 tourist season, but - Bezlov says - that looks increasingly unlikely.

“There were hopes that the new summer tourist season could be better than 2020 but with this tempo of vaccination, it is a fantasy,” he said.

But while it may not save Bulgaria’s tourist industry, at least it will enable Bulgarians such as Plamen Radomirsky, armed with their green vaccination passports, to travel as normal.

Update: Bulgaria's health minister said on Tuesday a new plan would see green corridors restricted to those over 60 and would only be held between Friday and Sunday.

Every weekday, Uncovering Europe brings you a European story that goes beyond the headlines. Download the Euronews app to get a daily alert for this and other breaking news notifications. It's available on Apple and Android devices.