Over the past two decades, the cricket icon has made a public transformation from international playboy to devout Muslim and anti-Western campaigner.

Cricket icon turned anti-corruption crusader Imran Khan declared victory in Pakistan's election Thursday, raising new questions about the nuclear-armed country's rocky relationship with the U.S.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

While no final result had been announced, Khan's promises to crack down on crippling corruption and transform a political scene long dominated by entrenched family dynasties appear to have won over voters in the militancy-plagued nation.

Over the past two decades, Khan has also made a public transformation from international playboy to observant Muslim and anti-Western campaigner.

But the dashing 65-year-old's support for Pakistan's controversial blasphemy laws, outreach to militant groups and apparent closeness to the country's military have worried some at home and abroad.

While he has been scathing of U.S. policies, such as the drone campaign against militants on the border with Afghanistan, Khan also said he would like to see ties "that will improve the situation" between Washington and Islamabad.

He will have to manage a tense relationship with the Trump administration, which has accused Pakistan of not doing enough to root out Taliban militants. Claims that Pakistan harbors and supports extremists fighting and killing Americans have long plagued relations between the two countries. In January, President Donald Trump suggested that he could withdraw annual support to Pakistan.

Khan also opposes the United States' open-ended presence in Afghanistan.

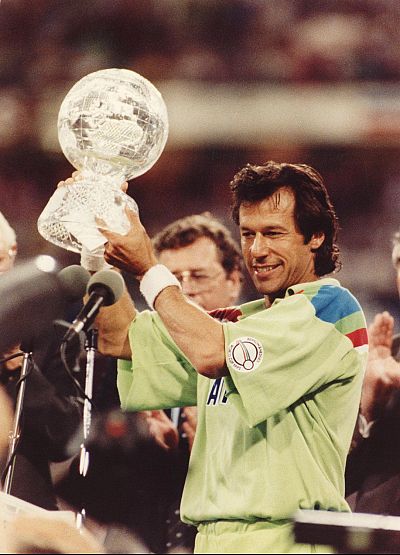

Born to a prosperous family in cosmopolitan Lahore and educated at Britain's Oxford University, Khan became a national hero when he led his country's cricket team to World Cup victory in 1992 — the only time the Pakistan has won the tournament.

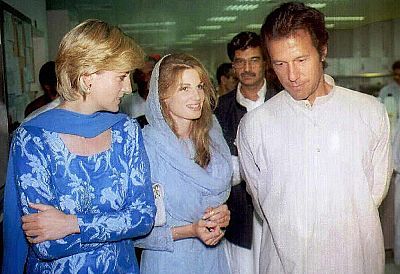

His early years in the spotlight saw him linked, and sometimes married, to glamorous women.

But his jet-setting ways have given way to a more devout figure who says he's driven to fight for the common man.

"We will adhere to austerity. We will be simple," Khan said in his first televised address to the country after the election. "We will strive for good governance. We will not live in palaces. We will build actual state institutions."

However, Khan has raised eyebrows for his views on role of Islam in society. He has publicly supported Pakistan's laws that make insulting Islam a capital offense and which rights activists say are used to persecute minorities.

In addition, his willingness to engage in dialogue with extremist groups has worried critics and more moderate Pakistanis.

"It is clear that he has decided to go all the way in seeking to, as it were, court the Islamist vote," said Farzana Shaikh, an associate fellow at Britain's Chatham House think tank who has written widely about Pakistan. "Having said that, he is himself known to be of a deeply conservative nature… since he abandoned his playboy nature."

Shaikh added: "What is more troubling is the way he conducted his election campaign and [called for] the need to preserve Pakistan blasphemy laws … and active courting of groups that are designated as terrorist organizations by the United Nations and indeed the state of Pakistan."

With almost half of the vote counted, election officials said Khan's Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf party was leading in 113 of 272 contested National Assembly constituencies. He was expected to be able to form a coalition government.

The election marks only the second civilian transfer of power since impoverished Pakistan was founded 71 years ago.

For months there have been allegations the Pakistan's powerful armed forces have fought to tilt the race in Khan's favor. Some 370,000 soldiers were stationed at polling stations across the Pakistan — around five times the number deployed at during 2013 election.

Khan campaigned on promises to oust political clans such as slain former prime minister Benazir Bhutto's family. Bhutto's son also ran in the election.

"He is presented as this face of an anti-corruption," Aaditya Dave, an analyst with British think tank the Royal United Services Institute. "He is not one of the establishment, and technically doesn't come from one of these families."

While his conservative social message won over many voters in this largely religious country, his promises about corruption and government services also spoke to millions.

Aside from pervasive official graft, most of the country of 200 million have to grapple with a crumbling public services, such as shortages in drinkable water and electricity blackouts, as well as a woefully inadequate schooling system. Illiteracy is over 40 percent.