Article contributed by Hugh Bohane, an Australian freelance journalist, English teacher and volunteer.

Article contributed by Hugh Bohane, an Australian freelance journalist, English teacher and volunteer. He has worked in both the media and humanitarian sector in Sri Lanka, Australia and, most recently, Greece.

I arrived at Park Hotel in Polykastro, in northern Greece, at the beginning of Ramadan to begin a short stint volunteering inside the refugee camps. Following the evacuation of the Idomeni camp in Greece last May, the refugees had been relocated to other sites around the country, mainly administered by the Greek military. The camps were and are still ill-equipped to handle large amounts of people and rely on the continuous support of volunteers and NGO groups.

The Hot Food Idomeni volunteer team launched their Rampack meal project at the beginning of June especially for the holy month of Ramadan. The program aims at providing the refugees with better food options than what is otherwise already provided by the army. In the past few weeks, the Rampack project has been supplying four camps, with a total of 4,500 people, at a cost of roughly €1,500 each day. Daily, each family receives fresh food, including flatbread, dates, tomatoes, cucumbers and fruit. Additionally, the team provides a hot chai tea stall in the Softex and Oreocastro camps.

After a brief meeting, Ingrid Kantaova, the Slovakian coordinator for new volunteers, directed me towards working with the Hot Food Idomeni team. I pitched my tent out the back of Park Hotel with some of the other volunteers in order to begin work the next day. I was impressed by how young a lot of the volunteers were. Some of them were in their gap year and others had already worked with refugees in their home countries. The crew’s current membership is made up of mostly Europeans, with a handful of the coordinators hailing from England. Englishman Paul Liengaard is one of the group’s leaders and, having worked as a director for both film and theatre, he is therefore well-suited to putting on large-scale operations such as this. Heather and Robbie Mack, a brother and sister duo, have worked as freelance event and volunteer managers and have recently been involved with the clean-up at the Glastonbury music festival. Kevin ‘Kev’ Potts, a former soldier from England, manages the chai tea van and explained the team’s mission to me, “It’s simple. We feed the people and cheer them up.”

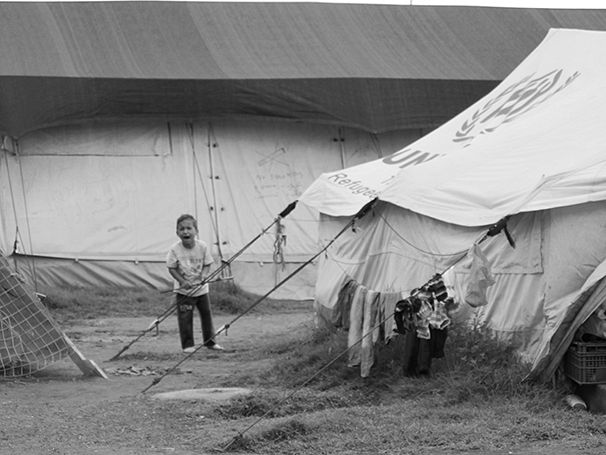

The day after, I met Inês Abreu Guerra, a film-maker and volunteer from Portugal. She was distributing a bag of toys made by terminally ill patients in Portugal to give to refugee children, as special gifts. I quickly realized I had made the right decision in joining this hard-working team. Ms. Guerra showed me around one of the unofficial camps called Eko, where I managed to get permission to take some photos. There I also spoke to an anonymous MSF worker, who said to me “When people get sick in this camp, they really get sick. When they get a fever it can last up to a week.”

Alison Thompson, an Australian full-time humanitarian who has been covering the crisis in Greece since it began, informed me that the Eko and Harra camps have both now been shut down. The refugees from these two camps are being moved all over the country, to hidden areas out of the public eye, and into dirty hot warehouses with lots of snakes and no running water. Volunteers are being shut out of a lot of these camps, but Ms. Thompson has been approved to go into the camps where she is providing solar lights.

On my first day, after we had finished packing the meals, Paul gave us a safety briefing and each volunteer was assigned one of two camps. Safety issues have been a concern for everyone living and working in the camps. I was assigned to Softex, a military-run camp about a 30-minute drive from Park Hotel. Upon arriving, our trucks were swamped by friendly though frustrated people. “My friend, my friend, this is no good!” one young Syrian boy said to me pointing at the camp. We split into small teams and began distributing the food to each tent. Indeed, the conditions and the environment of the camp weren’t good.

Some people were camping nearby a dark, moldy warehouse. A handful of Port-a-Loos had been placed in a row outside, but evidently hadn’t been cleaned regularly. Not far from the toilets was a small, polluted river. By nightfall, the mosquitoes were out in force, much to the discomfort of everyone. The food and hot chai tea are very popular with the folks and we needed to be careful everyone would get their fair share.

On the second night of Ramadan, there was a very tense atmosphere inside the Softex camp. People were very unhappy with the food they had received that day, and at one point it almost looked like we were going to have a food riot. To make matters worse, many people were struggling with the abstinence from smoking and any other vices during Ramadan. On the journey back, I chatted with Paul about the overall crisis and we lamented about the lack of a comprehensive future plan and how nobody in Europe is willing to accept refugees. While many people are referring to it as a ‘European crisis’, I thought that this should actually be labeled a global crisis. Greece, already strained by its own internal economic crisis, is left to cope with the immediate brunt of this.

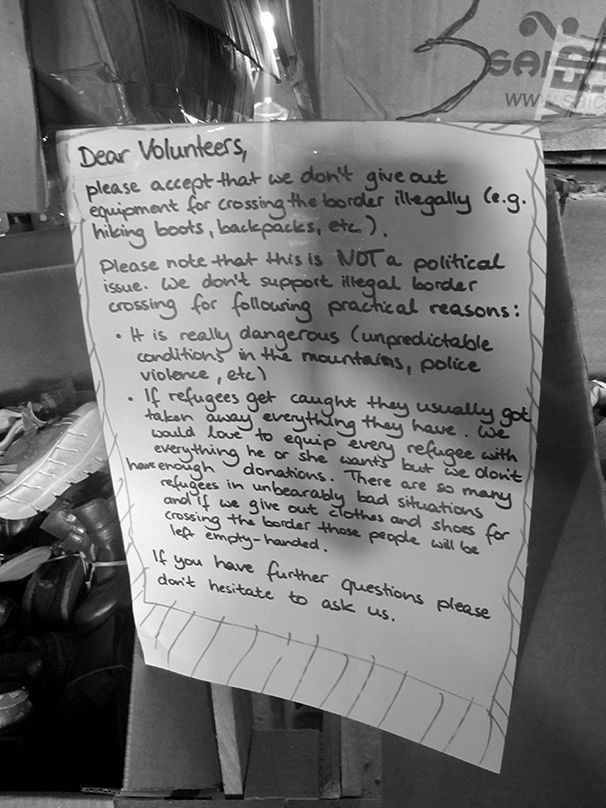

The following days and nights in the camps were fortunately much calmer. I made friends with a Syrian man named Abdullah, a soft-spoken man who could easily communicate in English. He and his younger brother had been stopped at the border of Greece and Macedonia and put into the camp. “I’m not angry. Sometimes I get sad but I’m not angry. This is my fate,” he told me calmly. I struggled to accept it: to me, this simply should not be anyone’s fate. One thing that surprised me about this crisis is just how many educated, middle-class people are stuck inside these camps without knowing where they will end up next. Abdullah asked me if I could bring him a pair of jeans and a pair of shoes from the main warehouse in Polykastro and so I did. I found the last pair of male trousers and a pair of shoes from a small selection inside. I discreetly handed him the bag with the items on my second last night. He was very grateful and I watched him disappear into the bowels of the camp.

I asked Heather Mack how people could help from the outside. “People can help by donating to Hot Food Idomeni, coming out and volunteering and by urging their own government to step up and take their share of the refugees currently in Greece. Thereby speeding up the registration and relocation process, and by supporting the Greek government in looking after the refugees in military camps. We would rather not be needed!”

Ms. Mack says that people have been fundraising across Europe for the team and some larger organisations have also given money.

On my last night of volunteering we all sat together on a long table in Park Hotel. A couple of Syrian men were playing a melancholic tune on an old piano, which they would habitually do in the evenings. “We often joke about stealing volunteers’ passports so they can’t leave!” Kev said to me. I contemplated the week that had been and realized that I hadn’t had time to process what I had witnessed and heard in the camps. The work this team does can be both physically and emotionally draining, but ultimately very satisfying. I pondered the hard fact that some of the volunteers have been working for two months or more in the camps and how they could start to feel insignificant. I explained to the group how I regretted that I could only be there for a short time. They assured me that everyone is needed both short and long term. My time working with this group had been like running away with some sort of humanitarian circus. I know I will be back again.

VIDEO: meeting refugee children at Eko camp and debriefing with the volunteers

All photos and video published courtesy of Hugh Bohane

Hugh Bohane is an Australian freelance journalist, English teacher and volunteer. He has worked in both the media and humanitarian sector in Sri Lanka, Australia and, most recently, Greece.