Following our first article highlighting key moments in the UK’s relationship with the European Union, Euronews now examines the 1990s as moves towards European integration gain…

Following our first article highlighting key moments in the UK’s relationship with the European Union, Euronews now examines the 1990s as moves towards European integration gain momentum. Meat Loaf’s 1993 hit echoes Britain’s dilemma over whether or not to join the EU’s forthcoming single currency.

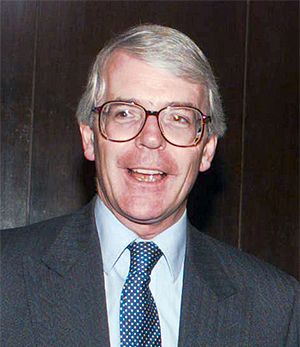

Margaret Thatcher is ousted from power in 1990 following a mutiny among ruling Conservatives over her leadership – with the issue of Europe contributing to the internal divisions. She is replaced as party leader and prime minister by John Major, who against the odds goes on to lead the Tories to victory in the 1992 general election. At the heart of the Thatcher government’s turmoil over Europe in the late 1980s has been the dilemma over whether or not to join the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) – the Community’s device for binding national currencies tightly together in the run-up to the planned single currency. Her two most senior ministers are in favour as a matter of economic policy. Thatcher has been opposed before reluctantly being won over, and Britain joins the ERM just before the end of her premiership.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

1992 – Black Wednesday panic

Amid a recession-hit domestic economy, a series of complicated international events – including a falling US dollar and tight anti-inflationary policy in post-reunification Germany – puts enormous pressure on the weak pound, which by virtue of its ERM membership, cannot float freely. In the course of one dramatic day on September 16, as currency speculators circle and pounce, attacking the pound with short-term selling, the government responds with a series of interest rate rises, desperately trying to keep the pound within its ERM limits. It doesn’t work: the UK crashes out.

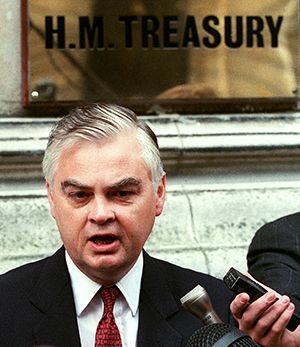

John Major (L) and Norman Lamont

John Major later writes that Black Wednesday “was a political and economic calamity. It unleashed havoc in the Conservative Party and it changed the political landscape of Britain”. In the aftermath, profound aftershocks linked to the traumatic events repeatedly hit his government. Hapless finance minister Norman Lamont begins by shrugging off the ERM catastrophe, saying he responded by singing nonchalantly in the bath and quoting Edith Piaf’s ‘Je Ne Regrette Rien’ – before being sacked and later becoming a notable eurosceptic. As hostility to EU integration grows, the government becomes increasingly embroiled in internal dissent over Europe – with Major once famously referring to a minority of eurosceptic Cabinet colleagues as ‘bastards’ – a description he defends 20 years later.

John Major later writes that Black Wednesday “was a political and economic calamity. It unleashed havoc in the Conservative Party and it changed the political landscape of Britain”. In the aftermath, profound aftershocks linked to the traumatic events repeatedly hit his government. Hapless finance minister Norman Lamont begins by shrugging off the ERM catastrophe, saying he responded by singing nonchalantly in the bath and quoting Edith Piaf’s ‘Je Ne Regrette Rien’ – before being sacked and later becoming a notable eurosceptic. As hostility to EU integration grows, the government becomes increasingly embroiled in internal dissent over Europe – with Major once famously referring to a minority of eurosceptic Cabinet colleagues as ‘bastards’ – a description he defends 20 years later.

1993 – Maastricht sets EU integration on the march

On November 1 the far-reaching and controversial Maastricht Treaty – named after the Dutch town where it has been signed the previous year – officially creates the new European Union. It adds new fields of policy co-operation among EU countries: foreign and security policy, and justice and home affairs. People in the 12 member states get European citizenship, total freedom of movement and new voting rights. The treaty also sets in motion the project for economic and monetary union.

In referendums the Danes reject it, the French only just approve it – in the UK it survives a tortuous passage through Parliament amid significant Tory rebel opposition.

Britain has negotiated the first of several special opt-outs on key parts of European legislation, on monetary union, and successfully manages to get the Social Chapter – covering issues such as workers’ pay, and health and safety – removed from the main treaty, securing an opt-out of that too in the process.

The Treaty also officially recognises the principle of “subsidiarity” – hardly a term to inspire wild enthusiasm, but one which is purported to safeguard national and local decisions, keeping EU federal power at bay. However, dissenting voices including eurosceptic academics argue that it is a mere sop to British public opinion and actually gives more power to the EU.

1997 – A breath of fresh Blair

By spring 1997, Major and the Conservatives have gone – replaced by a “New Labour” government under Tony Blair which appears far more pro-European in its outlook than its predecessor. The new prime minister is the first in Britain from the post-World War II generation, he speaks French and has pro-European instincts. The new government promptly drops the UK’s opt-out to the Social Chapter, and negotiations over new EU treaties, at Amsterdam and later at Nice – which aim to prepare the EU for impending enlargement – pass off without bust-ups with Britain.

Over the next few years Blair is also credited with playing a proactive role in contributing to reform of the Common Agricultural Policy – gone are the beef and butter mountains of the 1970s and 80s – and with pushing the Lisbon agenda, the grand EU plan to make the bloc more competitive in the 2000s. Ten years of Euro-Blairism until his departure from Downing Street in 2007 are seen in some quarters as having brought a positive record. That is not to say that he is averse to some EU-bashing when deemed necessary: during the 1997 election campaign he merrily signs an article in The Sun promising to ‘slay the dragon’ of federalism.

The late 1990s – to join or not to join… the euro

By the mid-nineties the onward march towards the EU’s single currency is in full swing. In Britain, partly due to internal divisions on whether the UK should join, neither main party particularly wants to highlight the issue. As prime minister, John Major steers a middle course: he cannot say that Britain will never join the euro, but – he argues – that time has not yet come.

With Labour in power from 1997, initially there is confusion. Andrew Marr writes in his book ‘A History of Modern Britain’ that Tony Blair has rival pro-euro and anti-euro advisers: “Pro-euro journalists went to see him and came away thinking he was on their side. Anti-euro journalists had the same experience”. A senior government adviser even jokes that he hasn’t bothered reading the latest speech as the policy has probably changed in the hour since it was written.

In fact the new prime minister is broadly in favour of joining the single currency at some stage, but is conscious of how hostile the press will be to ditching the pound – indeed, a year after Labour’s is elected, the tabloid runs a front-page headline asking whether Blair’s apparent pro-euro stance has made him ‘the most dangerous man in Britain’.

In the end Finance Minister Gordon Brown – more ambivalent over the euro than Blair – and his advisers produce five economic tests to be passed before Britain can join. The single currency is duly launched in 1999 although notes and coins only arrive in 2002. After years of assessment, the UK Treasury reports in June 2003 that the conditions have not been met. The issue is further kicked into the long grass after Brown becomes prime minister four years later.

Given the euro’s subsequent turbulent recent history, Brown has often been credited with the decision to keep Britain out of the single currency – although, along with rumours that the five tests were dreamed up in the back of a taxi, this interpretation of events has been questioned.

In our third and final article on the UK’s relationship with the EU , we look at the effects of EU enlargement as migrant workers from the ex-communist states flock to Britain, contributing to the rise of Ukip, while David Cameron’s tussles over the EU ultimately lead to the pledge to hold an In/Out referendum.