The UK faces new border constraints as it struggles with supply shortages, the fruit of the government's rejection of EU rules and overseas labour.

The end of the holiday season heralds the return to centre stage of a number of burning Brexit-related issues this autumn.

Grace periods that have preserved previous UK-EU arrangements are due to end at various stages, imposing new constraints on already-disrupted trade.

Britain faces new checks on EU imports just as it struggles with labour shortages and supply chain disruption, not to mention the ongoing pandemic.

COVID-19's hit to the economy has been hard to extricate from that of the UK's departure from the EU. Yet business groups say the impact of Britain's first few months outside Brussels' orbit has been severe — exacerbated by the sovereignty-first strategy of Boris Johnson's government.

A cliff-edge concerning changes in Northern Ireland has been avoided — but the renewed delay has done nothing to resolve fundamental differences over the protocol dictating post-Brexit rules.

Euronews looks at five problems on the prime minister's plate this autumn — affecting food supplies in particular — that his own Brexit plan has largely reaped.

1. Lorry drivers: UK government 'fails to understand shortage'

Over the summer problems with food supplies have become increasingly apparent in the UK. Brexit and the COVID pandemic have combined to leave some supermarket shelves empty.

A significant factor is a shortage of lorry drivers. The freight transport industry has estimated that it lacks some 90,000 — the result of a year-long suspension of training and testing during the pandemic, but also due to an exodus of EU hauliers.

Some 14,000 left the UK for their home countries in the year to June 2020, and only 600 have returned, according to research carried out for Logistics UK. Under the UK's post-Brexit immigration rules, new drivers from Europe can no longer come to work in the UK as easily as before.

However, the British government has rejected calls from the industry to grant European drivers temporary visas, instead easing restrictions on hours and telling businesses to hire UK-based workers.

That brought an angry response from the Road Haulage Association on August 31. "Ministers and senior officials continue to fail to understand the lorry driver shortage," said Duncan Buchanan, RHA Policy Director for England and Wales, highlighting the time it takes to recruit and test new drivers.

"There is something wrong with this system that needs to change to address staff shortages of skilled workers," he added, criticising the omission of lorry drivers from the government's "shortage occupations list", designed to identify problems and facilitate recruitment.

In June the RHA coordinated an appeal from transport and food industry groups, who wrote to the prime minister warning that a chronic shortage of lorry drivers could disrupt supplies. The UK's departure from the EU was one of several factors listed.

Logistics UK and the British Retail Consortium (BRC) followed up in August, issuing a joint appeal for temporary visas for EU drivers to alleviate the problem.

2. Other labour shortages: Christmas supplies 'at risk'

Acute labour shortages have been reported in other areas too, including the care sector, construction, hospitality and agriculture — all particularly reliant on EU workers in recent years.

The British food and drink sector has also called on the UK government to alter post-Brexit immigration rules.

A cross-industry report published on August 26 warned of "a very real chance that they (labour shortages) could quickly reach breaking point". It highlights several reasons, claiming the UK's post-Brexit "points-based immigration system has locked out low skilled workers" such as "drivers, butchers and seasonal workers".

The National Farmers' Union (NFU) has joined several industry bodies to ask for a 12-month "COVID-19 Recovery Visa" to facilitate overseas recruitment and other measures including a review of the impact on the food sector of the end of free movement from the EU.

"Farm businesses have done all they can to recruit staff domestically, but even increasingly competitive wages have had little impact because the labour pool is so limited — instead only adding to growing production costs," said NFU president Tom Bradshaw.

The labour shortages have created a surplus of livestock, with thousands of pigs awaiting slaughter. Supply problems have also led fast-food chains to take emergency measures: McDonald's pulled milkshakes from its menus, Nando's shut dozens of outlets temporarily, while KFC warned some items were out of stock.

A survey by the trade body Scotland Food and Drink in August found that 93% of companies had vacancies they were struggling to fill. In a joint industry appeal, several groups call for recruitment to be expanded to EU and other overseas workers.

"Brexit has been an enormous shock to the labour market; a Brexit implemented in the middle of a pandemic, when supply chains were already straining," noted CEO James Withers in a Twitter thread, calling for government action to prevent the situation from deteriorating. "And yes, Christmas is at risk," he added.

3. UK import controls to come into effect

Although the central thrust of Brexit was to "take back control", in fact the UK has yet to impose full controls on EU imports.

Checks that were originally planned to have started in the spring and summer were postponed last March, the government saying businesses needed more time to adapt to "new processes and requirements".

However, in the coming months as more grace periods end, these changes are finally due to come into effect.

From October 1, more agri-food products imported from the EU into the UK will have to be pre-notified to the UK authorities and will need health certificates. From January 1, 2022, this will cover all such products.

Also from New Year's Day, full declarations will be required, on customs and for safety and security. Physical checks on animal and plant products will begin. "Rules of origin" requirements will be more stringent.

From March 2022, checks will begin on live animals and all regulated plants and plant products imported from the EU. But there risks being a shortage of vets needed to carry them out. The number arriving in the UK from the EU has plunged dramatically in 2021, partly attributed to stringent new recruitment criteria.

According to Archie Norman, head of Marks & Spencer, the imminent UK import controls "risk lumbering French cheese producers and Spanish chorizo manufacturers with the same costs as we have faced trying to export food to the EU".

4. Red tape: UK-EU traders cry for help

Even before the new checks take effect, post-Brexit border bureaucracy has caused significant disruption to traders between the UK and the EU. Many continue to struggle with customs declarations, other paperwork, transport delays and higher costs.

Some importers point the finger at the British government for cumbersome procedures and onerous restrictions.

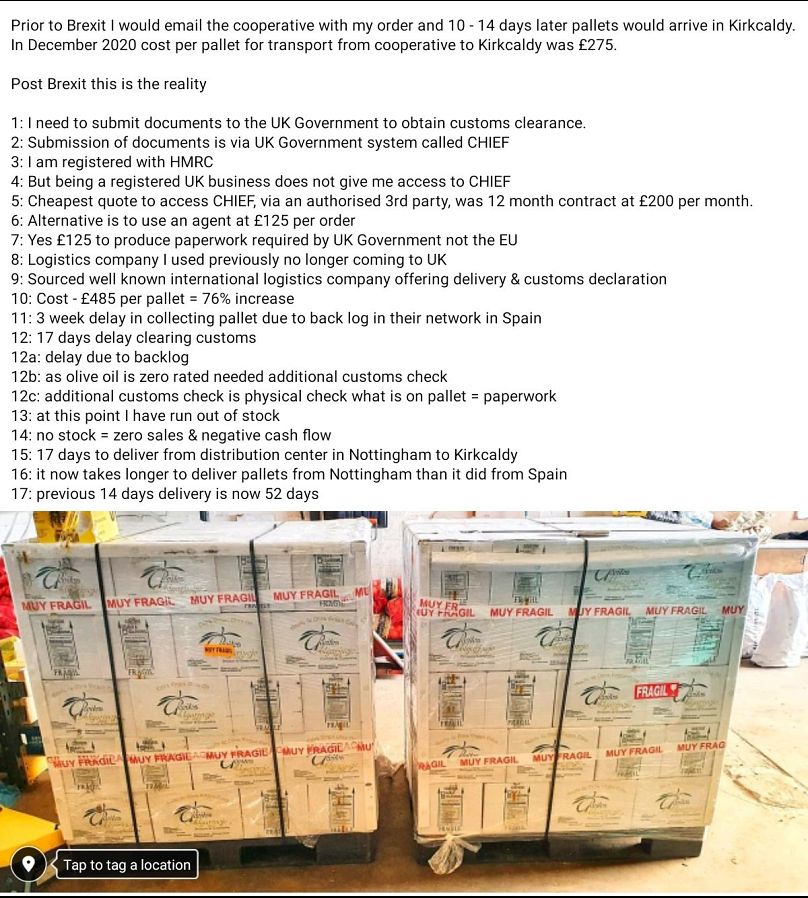

Callum Henderson, whose company Great Oil UK imports olive oil from southern Spain, says some of the extra red tape resulting from Brexit is UK-imposed. He has listed the complicated procedure which has brought a 76% increase in transport costs, and significant delays to deliveries.

"Previous 14 days delivery is now 52 days," he noted in July.

Wine industry's woes

"Logistics to the UK have never been so dire in the 29 years I have been trading, and the delays for stock coming over from the EU show zero signs of improving," Welsh-based wine importer Daniel Lambert said on Twitter, adding that post-Brexit, "days have become weeks".

The paperwork challenge is set to get worse, he warns, citing future constraints and inspections the British government is due to impose on organic wine imports from the EU that are "beyond the realms of stupidity".

Tim Ford of Domaine Gayda, a winery in France's Languedoc region which exports to the UK, says on the other hand that the new paperwork is "posing no issues", although "the wait time for a pick up is probably double last year".

He is worried, however, about another UK requirement due to take effect later in 2022, when all wine imports will need to include importer details on back labels.

"We will be able to handle most things but the back labelling rules... are going to be a game-changer and I have no answer as to how we will handle that," he told Euronews. "We really hope this one can be kicked down the road!"

In another move which does temporarily ward off more trouble for businesses, the government has postponed by a year a requirement for goods sold in the UK to carry a new British product safety mark, which had been due to take effect next January.

'A fandango of bureaucracy'

Figures from the Food and Drink Federation (FDF) released on September 2 show that UK exports to the EU plunged by 15.9% in the first half of 2021 compared to the same period in 2020 (and by 27.4% compared to 2019). A rise in food and drink sales to non-EU countries of 13% was not enough to prevent an overall drop of 4.5%.

An editorial in the Mail on Sunday on August 29 blasted "the curse of border bureaucracy", slamming "obsolete" EU customs rules holding up UK exports as well as the UK's own "tiresome and self-harming restrictions" on imports.

Writing in the same paper, M&S boss Archie Norman said the rules were "at odds with a modern, fresh food, supply chain between close trading partners... a fandango of bureaucracy". M&S vehicles, he added, travel to ports with an average of 700 pages of documentation.

Neither his article nor the editorial mentions the UK's voluntary departure from the Single Market and Customs Union. That decision was taken back in January 2017, Theresa May's government judging that the conditions attached to staying in would be incompatible with voters' wishes expressed in the EU referendum the previous summer.

As the UK's Institute for Government explains, border formalities are necessary as the UK and the EU no longer apply the same customs rules, regulatory standards or enforcement mechanisms. They exist to ensure that tariffs or duties are paid, standards are met, to prevent smuggling and comply with international obligations.

Government urged to 'own trade deal' it struck

The last-minute EU-UK trade deal negotiated by Boris Johnson avoids tariffs and quotas but does little to streamline border processes, the institute points out.

In a survey published in June, North East England's Chamber of Commerce found that 75% of its internationally trading members reported the Brexit trade deal had negatively impacted their business. Well over a third had suffered a loss in trade with the EU — a figure dwarfing the equivalent for non-EU trade, suggesting that the blame lay with Brexit not the pandemic.

Its outgoing chief executive, James Ramsbotham, wrote to Boris Johnson in July with a list of recommendations, beginning with a demand for the government to "take ownership of the trade agreement between the UK and the EU, that they negotiated, signed, and implemented, and acknowledge the issues that it has caused and continues to cause for businesses".

Archie Norman calls for agreement on "equivalence" where the EU and UK recognise each other's standards. But Brussels ruled this out during the negotiations, citing the UK's rejection of free movement and EU court jurisdiction.

5. Northern Ireland: delay does not resolve row

Imminent changes affecting Northern Ireland have been delayed again, heading off what could have been the biggest potential flashpoint in EU-UK relations this autumn.

However, both sides remain at odds on the implementation of the protocol agreed as part of the Brexit divorce deal.

On September 7 the British government said it was again postponing new rules on goods sent from Britain to Northern Ireland.Grace periods had been due to expire at the end of September, which would have meant a ban on chilled meats, and new documentation and checks for animal and plant products.

The European Commission responded, saying they "take note" of the latest UK statement, but flagging that "we will not agree to a renegotiation of the Protocol."

The reason for the internal UK checks is to show compliance with EU law, as Northern Ireland continues to follow EU rules in areas such as customs, agriculture and product standards. But further changes risk compounding trade disruption that revived tensions in Northern Ireland earlier this year, particularly in unionist communities.

The protocol's troubled implementation — the joint committee overseeing it identified more than two dozen specific problem areas — has plagued EU-UK relations this year.

In July Brussels suspended legal action against London, begun after the UK unilaterally extended two grace periods earlier this year, to allow some breathing space. This followed a call by the British government for a "standstill period" while discussions continue.

The UK's latest proposals — reinforced in a speech by Brexit negotiator David Frost on September 4 — amount to a demand for a substantial overhaul of the protocol. Brussels has rejected a renegotiation, but says it is ready to engage with the British government to seek solutions.

London has threatened to override the protocol, accusing Brussels of "legal purism" in applying it. But Boris Johnson was its joint architect and Northern Ireland's binding ties to multiple aspects of EU law are there in black and white in the text.

The treaty's aim is to reconcile UK divergence under Brexit with the need to avoid a hard land border on the island of Ireland. The EU insists it must be applied in full to protect its Single Market. The UK calls for more flexibility, pointing out that the agreement seeks to protect all communities.

A report by a House of Lords committee published at the end of July criticised "fundamental flaws" in the approach of both sides: "lack of clarity, transparency and readiness on the part of the UK; lack of balance, understanding and flexibility on the part of the EU"... and concluded there was "an urgent imperative for all sides to make concerted efforts to build trust".

Boris Johnson promised to "Get Brexit Done" and duly took the UK out of the EU with a deal. But the decision to leave the EU's Single Market and Customs Union, coupled with the government's emphasis on sovereignty, have created significant barriers with the UK's biggest trading partner that look set to be long-lasting.

As Peter Kellner comments for the think-tank Carnegie Europe: "The larger truth is that, on this as on so many other things, the UK chose Brexit without comprehending the full consequences of its decision."

This article originally published on September 6 has been updated to take account of new developments concerning Northern Ireland.

Every weekday, Uncovering Europe brings you a European story that goes beyond the headlines. Download the Euronews app to get a daily alert for this and other breaking news notifications. It's available on Apple and Android devices.