As Europe moves towards its net zero goals, how can the bloc protect its economy and industries when its supply chains rely so heavily on China for a wide range of materials? Watch our Crash Course on the roadmap ahead.

Debt, inflation, wages, and jobs ... We know that it's tricky to understand how the economy works. That's why every episode of Real Economy brings you a one-minute Crash Course to bring you quickly up to speed on the big picture. We explain the headline concepts and lay out how public policy is reacting to changing current affairs and economic trends. Watch your one-minute Crash Course in the video above.

China, the world's second-largest economy, is currently a fundamental piece of Europe's green energy puzzle. The European bloc is 98-100 per cent reliant on Beijing for the supply of raw minerals such as lithium, magnesium, cobalt and manganese which are essential to manufacturers in the technology and defence industries.

According to the Spanish think tank, the Elcano Royal Institute, China controls some 37 per cent of global rare earth reserves, which increases its geopolitical power. While these minerals are not mined in China, they are shipped there for processing and are fundamental for producing batteries, wind turbines and solar panels.

Chinese-made electric vehicles are in growing demand on the European continent. In November 2022 alone, exports of Chinese-made EVs to Europe were valued at €2.85 billion.

While the majority of these exports consisted of parts and vehicles designed by European automakers, they were all manufactured in China. Audit and assurance giant PwC estimates that up to 800,000 Chinese-built cars could be exported to Europe by 2025.

Meanwhile, solar power use in the EU soared almost 50 per cent in 2022. But these panels are not produced in Europe, 80 per cent of Europe's solar panels come from China, and imports were valued at €21 billion in 2022 alone.

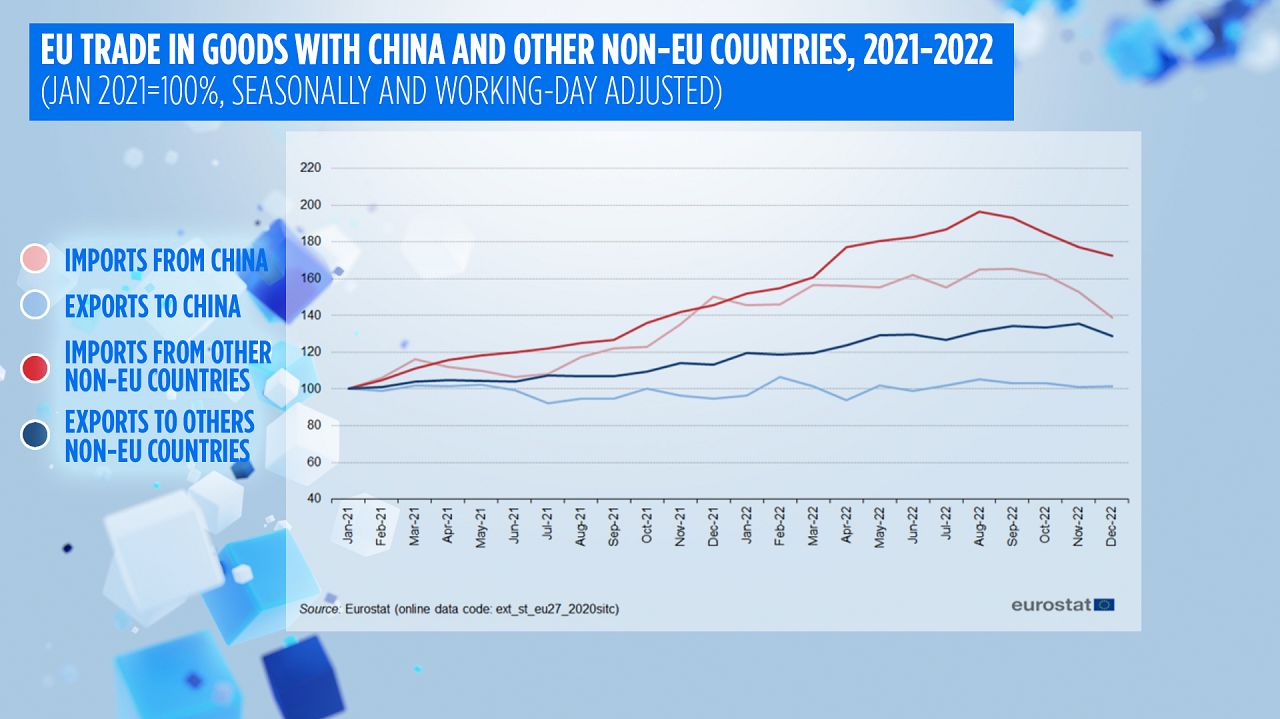

Europe is becoming more reliant on China for imported materials which far outweigh the value of its exports to China. According to Eurostat, Europe's trade deficit with China stood at €36 billion in September 2022 before it dropped to €27.4 billion in December 2022.

However, this figure was just €14.6 billion in January 2021.

So why is dependency on China a potential problem for Europe and how does it plan to implement its 'derisking' strategy?

All one's eggs in one basket

Like the EU, Japan was once heavily dependent on China for the supply of critical minerals. However, these strategic resources became 'trade weapons' in 2010, when China blocked exports to Japan.

A dispute over a fishing trawler prompted Beijing to cut off all rare earth exports to Tokyo, forcing Japan to set up trade deals with Australia to reduce its dependence on China.

However, the move highlighted the need to diversify supply chains to reduce vulnerability.

As China's economy grows and Europe's demand for Chinese materials grow, Brussels finds itself in a similarly vulnerable situation; growing tensions over China's stance on the war in Ukraine and potential threats to global order have pushed Europe to look for alternative trade routes.

Brussels wants to decrease its dependency on China and in the words of the European Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen, "rebalancing" economic ties is key.

De-risk, not de-couple

So how does Europe propose reducing its reliance on Beijing while ensuring that trade agreements continue to promote prosperity for both China and the EU?

Brussels wants to make competition between the two powers fairer by increasing transparency and reciprocity. It also wants to reassess the Comprehension Agreement Investment (CAI) strategy to mitigate risks to the EU's economy and security.

For this, the EU has devised an economic de-risk strategybased on four pillars:

- Making Europe's economies and industries more resilient and competitive, particularly in the digital, clean-tech and health sectors

- Helping Europe make better use of the tools it has to deter economic coercion

- Devising new policies to protect companies' capital and expertise to ensure they are not used to enhance rival military and intelligence capabilities

- Aligning with other trade partners, building and modernising free trade agreements to strengthen supply chains and diversify trade

If Brussels successfully makes progress in these four areas, it could help the bloc regain control of its supply chains, map the future of its energy systems and ensure a smoother transition to a cleaner and greener Europe.