The world's leaders convened at Sharm El-Sheikh in Egypt to decide on the next set of global strategies on tackling climate change. This year felt like a turning point in the fight against climate disaster. Our panel will discuss whether it was a success or a failure.

In the wake of the COP27 climate summit in Egypt, Climate Now debated the final declaration from the summit, asking where it failed, where it succeeded, and what needs to happen next before COP28 in 2023?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Euronews assembled a panel of climate and political experts to discuss the goals and outcomes of COP27.

The expert panellists were:

- Lars Peter Riishøjgaard, Director of Earth System Branch, World Meteorological Organization

- Mia Moisio, Climate Action Tracker Project Lead, NewClimate Institute

- Lídia Pereira, MEP, Partido Social Democrata

- Dr Carlo Buontempo, Director, Copernicus Climate Change Service

The debate was streamed on Wednesday 23 November 2022. You can watch the highlights of the debate in the video below:

What's the climate situation today?

When leaders and delegates from 190 countries sat down in Sharm El-Sheikh in Egypt, the global picture of the climate crisis appeared to be of even greater urgency than at Glasgow’s COP26 last year.

The UN's climate summit came in the wake of dramatic floods in Pakistan, record-setting heat waves in Europe, and natural disasters amplified by global warming in many other countries.

Global temperatures remain at a statistical high with the average surface air temperature 1.2°C above the pre-industrial average. Alarmingly, the temperature increase is as high as 3°C in the Arctic, according to Copernicus’s European State of the Climate 2021 report.

Sea ice, glaciers and ice sheets have lost mass, and sea levels are now rising at 4.5 mm per year on average.

The Paris Agreement sets a goal of limiting warming to 1.5°C above the pre-industrial average. However, in 2021, the average temperature had risen by 1.2°C, and a UN study found that the risk of breaking the 1.5°C level at least once in the next five years was around 50 percent.

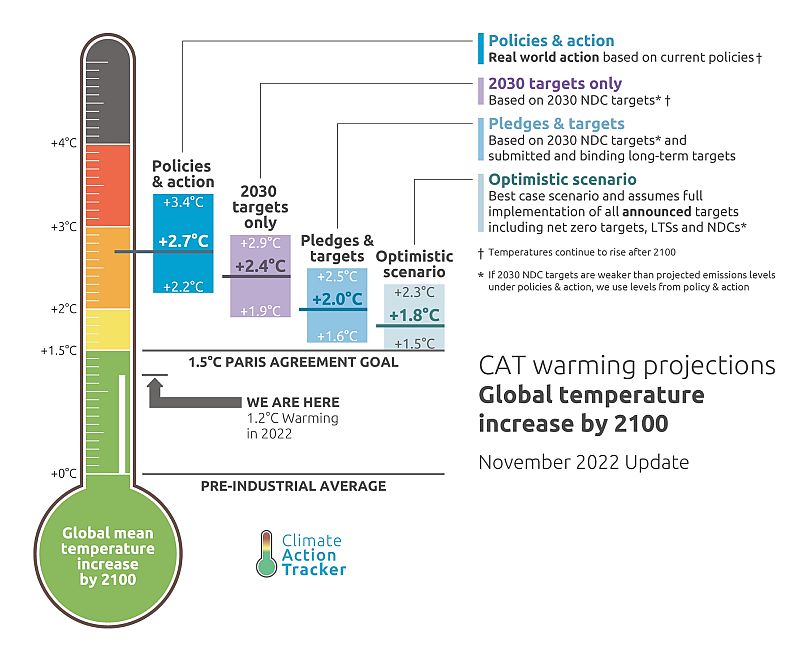

"We're heading to 2.7°C of warming by the end of the century with the actions that governments are actually taking," warned Moisio.

And yet, there has been little movement to reduce many carbon emitting fuels.

“More pipelines have been announced, more exploration into new gas, more LNG terminals. If these plans materialise, then we’re really endangering the 1.5°C temperature limit,” Moisio said.

As temperatures rise from continued carbon dioxide and methane emissions into the atmosphere, the number of extreme weather events is projected to increase, too.

COP26 in Glasgow was a moment of reckoning for countries. While many critics found there was little considered action implemented, there was recognition at the increasing emissions gap and the need to strengthen 2030 targets by COP27. However, despite many warm words, action on emissions reduction is slow.

The UN international treaty on climate change, the Paris Agreement, requires countries to outline and communicate their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to reduce carbon emissions.

When taking every country’s NDCs into account, there is still a significant gap between the planned reduction in emissions and the action required to reduce global warming to a range within 1.5 and 2°C.

When implemented, the NDC pledges from Paris Agreement countries will reduce global emissions by between five and 10 per cent by 2030. To get on track for limiting global warming to the desired level, the figure should be between 30 and 45 per cent.

The loss and damage fund, a COP27 successes

Despite the dire prognosis for emissions gaps and rising temperatures, the debate first turned to the positive outcomes of the recent summit.

COP27 focused for the first time on wealthy countries footing the bill for damages to lower income countries likely to be hit harder by extreme weather.

Known as the Loss and Damage fund, it was agreed in order to aid with the harm being done to the world’s “most vulnerable countries”.

Pressure from developing nations was spearheaded by Pakistan, a country reeling after exceptional floods killed over 1,700 people, left over two million people displaced and cost the country €39 billion.

Over the past couple of years we’ve witnessed the climate emergency,” Moisio noted. “So it’s really important that we see this loss and damage fund.”

While Pereira agreed that answering the plea for the fund was long overdue, she noted “there is not yet an agreement on how the finance should be provided and where it should come from.”

Moisio also concurred that without clear routes of funding the fund, as it stands it is merely the promise of a potentially empty bank account.

How will climate change accountability be given to environmental disasters was another contention.

For a long time, Buontempo has been asked by journalists whether an extreme weather event is the result of climate change. It’s a question with rarely a clear answer. “You cannot attribute a single event to climate change,” he explained. You can often only say the event is becoming “more common because of climate change.”

Buontempo hopes that the loss and damage fund will raise the bar for attributing events to climate change. “There will be pressure from the country that experiences the extreme event and go with the claim that it would have been impossible without climate change.”

Another controversy comes from the definition of developing countries the fund is applicable to. The text used around the fund is based on a 1992 agreement.

Many countries have seen significant growth since then, and it seems to many observers to be unfair for countries such as China, Saudi Arabia and Russia, which are major greenhouse gas emitters, to not be considered wealthy enough to contribute to this new fund to help those most impacted by climate change.

Where all the panellists agreed was that the fund itself is only a small step that ignores the more important job of mitigating climate change.

“Whatever we do on loss and damage will never be sufficient if we don’t address mitigation,” Pereira said. “On this particular topic, I think COP27 was far from being successful. There is still a lot to be done for next year, but the clock is ticking.”

COP27’s series of disappointing events

The lack of success on climate mitigation was the reason why “COP27 was not a good COP for the planet or humanity,” Pereira said.

The basic contention was that policies needed to reduce the emissions gap were not agreed upon at COP27.

A goal to have global emissions peak by 2025 was not created. The clause was expected in the final text, but was omitted due to pressure from multiple countries.

Just 29 countries submitted updated NDCs to the UN in 2022.

Pereira was notably exasperated by many countries’ willingness to undermine the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C threshold, stating that “climate diplomacy” and “multilateralism” were the only means to winning the fight against climate change.

Pereira noted the relative successes of Europe, but insisted on the importance of getting real change from other continents. “China and India are big CO2 emitters. If they don’t understand that they also have to take action. Europe cannot act alone,” she explained.

Disagreeing somewhat, Moisia noted that keeping temperature increase under 1.5°C is a global challenge and one that even with all EU prerogatives in place, it isn’t doing enough.

Moisia then brought attention to the Climate Action Tracker that the NewClimate Institute creates. By tracking the largest carbon emitters on the planet, they can project where the climate is actually heading.

“We’re heading to 2.7°C of warming by the end of the century with the actions that governments are actually taking. This is really catastrophic,” Moisio reminded.

Even if all the Net Zero targets that governments have suggested but not fully implemented were put into place, warming will still reach 1.8°C according to the tracker.

Forecasting the future

“For many years, climate scientists have been told that we’re too over dramatic and cause panic without reason,” Buontempo says.

“After the summer, people started saying the opposite. We were too cautious!” he adds.

The plight of the climate forecaster has always been a tough one, to persuade the public and policy makers that climate disaster is possible unless massive action is taken.

A large part of the debate focused on how climate forecasters have been increasingly proven right on their weather predictions. “If you look at 20 years ago, we were pretty much saying what’s happening now,” Buontempo says.

“I think this should increase the level of trust to projections,” he hopes.

Considering a graph of CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, Riishøjgaard reiterated Moisio’s point about climate change as a global issue, not something that can be considered on just the European scale.

“The climate system reacts to what is in the atmosphere, it doesn’t react to what individual countries or individual groups of countries claim they’re emitting or claim they’re offsetting,” Riishojgaard said.

The amount of carbon in the atmosphere is steadily creeping up and not enough is being done to combat it, he added.

Atmospheric observation, while dealing with incredibly complicated modelling systems, is the most important way to monitor the increase of carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere according to Riishøjgaard. Although other parties at COP27 argued that emissions should be charted by national self-reporting, as per the Paris Agreement.

“I think that’s a little bit naïve,” Riishøjgaard said. “It’s like asking you to be the official record keeper of your own bank account.”

Was COP27 a success?

How did countries fare during this year’s COP27? International headlines paint a picture of how the summit was seen in Europe.

- “World still ‘on brink of climate catastrophe’ after Cop27 deal,” wrote the Guardian.

- “Death on the Nile” was Politico’s summary.

- “COP27, between hope and despair” was Le Monde’s take.

- “Limiting warming to 1.5°C has become a hollow phrase after the climate summit,” wrote a Volkskrant editorial.

In Glasgow, then COP president Alok Sharma said the 1.5°C target was still in reach but “its pulse is weak”. This year’s president Egyptian foreign minister Sameh Shoukry has reiterated that the goal is within reach.

However, not everyone is convinced by the outcome of the summit. “It does not bring a high degree of confidence,” European Commission Executive Vice President Frans Timmermans said of the final declaration. “It does not address the yawning gap between climate science and climate policy.”

A visibly angry Sharma said of the summit’s conclusion: “Emissions peaking before 2025 as the science tells us is necessary? Not in this text. Clear follow-through on the phase down of coal? Not in this text. A clear commitment to phase out all fossil fuels? Not in this text.”

What needs to happen at COP28?

When COP reconvenes next year in Dubai, there are big questions left hanging from this year’s summit.

Biggest of all is how the world will have fared in the intervening year. After a year of floods, droughts and heatwaves, the climate emergency is more pressing than ever.

“What needs to happen is the CO2 and methane concentration that’s going up irrespective of COP needs to level off and eventually stabilise, if not decrease,” Buontempo said. “The only way we know to do that is to reduce our emissions.”

On a hopeful note, Moisio pointed to the ways governments can act in emergency mode. “We’ve seen this with the Covid-19 pandemic and now with the energy crisis following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Governments can do things that were previously completely unthinkable.”

“We’re in the middle of an emergency, and we need to treat it as such,” she said. To do this, there needs to be a larger diplomatic effort to bring major players like the US and China into multilateral talks.

“The major emitters need to put forward new targets ahead of COP28,” Moisio said.

She also said that goals of 1.5°C are pointless without phasing out fossil fuel. “There have been some positive movements with the US in favour of texts to phase out fossil fuels,” she noted. “But we need to see that kind of leadership from all the major oil and gas producers.”