As Saudi Arabia's largest contemporary art platform hosts its third edition, the artistic directors of the Diriyah Biennale reveal how ancient Bedouin journeys have inspired a radical new vision.

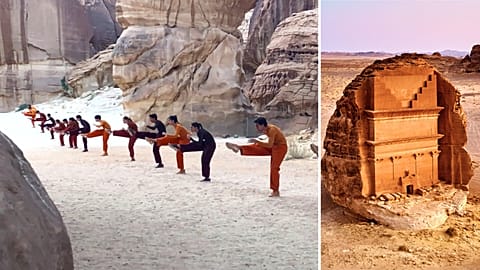

In the historic site of Diriyah, northwest of Riyadh – where UNESCO-listed ruins mark the birthplace of the First Saudi State – over 65 artists from 37 nations have gathered for what has become Saudi Arabia's most ambitious contemporary art event.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2026 takes its title from a colloquial Arabic phrase evoking the cycles of nomadic life: In Interludes and Transitions. The phrase references the rhythms of Bedouin communities moving between encampments and journeys across the Arabian Peninsula, a state of perpetual flux that nevertheless maintained connection and continuity.

But this isn't an exhibition about nostalgia or heritage preservation. Led by artistic directors Nora Razian, Deputy Director and Head of Exhibitions and Programmes at Art Jameel, and Sabih Ahmed, a curator and cultural theorist serving as Projects Advisor at the Ishara Art Foundation in Dubai, the biennale reimagines the world as a series of processions – movements that entangle humans with planetary, spiritual and technological currents.

More than 22 new commissions are being presented across the JAX District, a burgeoning creative quarter near the historic At-Turaif UNESCO site.

Taking place in repurposed warehouses with scenography by Italian design studio Formafantasma, the exhibition eschews traditional cartographic thinking for what the directors describe as a "sonic methodology" – an approach based on echoes, reverberations and rhythmic flows.

We spoke to Razian and Ahmed about how Arabic poetry shaped their curatorial vision, the politics of movement in an age of forced stillness, and why launching Saudi's contemporary art scene with a biennale rather than an art fair represents a fundamentally different proposition.

The biennale's title, In Interludes and Transitions, references nomadic journeys in the Arabian Peninsula. How did processions become such a central idea?

Nora Razian: We were thinking from the very beginning about oral histories and language and poetry and how that's really a unifying mode of storytelling and recording history in this region. And that, in fact, Arabic poetry did emerge from here. And one of the central metres of Arabic poetry actually emerged from the rhythm of moving through the desert – it's a specific rhythm that's kind of synced to animal steps. These long journeys, the processions, actually created cultural form. And I guess that's very rooted in this location, along with many others. But that was the kind of genesis for this idea. And also, you know, processions can be joyful and celebratory, but they can also be commemorative. We really wanted to evoke this idea of a coming together of people and a notion of kind of continuity that happens within those kinds of flows.

Sabih Ahmed: A big part of our initial conversation was looking at the idea of transmissions and transmission of stories through bodies, transmission of histories, transmission of commodities and goods – that is to say various technologies of transmission. This idea of transmission then got embodied into processions. First we were looking at how things transmit in the world, then we came to realise that we are the transmitters ourselves. And if we are the transmitters, that also means that everything is in a state of “procession”.

How does that translate into the visitor experience?

SA: We wanted to convey this idea of a levitating scenography, essentially. The spaces were quite challenging. They're very big warehouses. And so, we were thinking of how to divide a space, but keep a flow, keep a continuity, and keep conversations between works. But we didn't want a heavy exhibition architecture. We wanted to keep things really feeling light. And so there's a kind of aesthetics of fragility of sorts that really carries through, because every work is an assemblage of many things, both metaphorically and materially.

NR: Actually something that I brought early into the conversations when we were discussing transmission was to look at the sonic as a methodology. And here sonic does not mean simply sound as a medium, but rather referring to echoes and reverberation. This takes you outside of the usual ‘archaeological’ approach, which normally means digging deep, looking at archives and documents. You see this kind of methodology applied curatorially across the biennale. It's the whole biennale being approached not archaeologically, not cartographically, but sonically.

There are artists from over 30 nations participating. How did you navigate questions of representation versus curatorial coherence?

NR: I'm not sure we were thinking about representation per se, but thinking from here – rather than thinking about what here looks like from the outside, it’s about thinking outwards from here. So, asking: where do we connect to, and what histories pass through here?

SA: Yeah, we’re doing that rather than trying to represent the world in some way. For at least the past few decades there has been a lot of focus on the local and the global in biennales. I think, at least for us, we're kind of past that. It's not about globalisation and how globally connected people are because of information or supply chains or economic models, but really the world is a very much more tenuous set of relations because of, say, ecology, because of affinities and solidarities of shared experiences, even though people have never met one another, say, in times of vulnerability and fragility. I mean, COVID is a testament to that.

There's a philosopher that's inspired some of our thinking, Thomas Nail, who put it very nicely. His whole work is around what he described as 'kinopolitics', a politics of movement, a philosophy of movement as a starting point, rather than things being stationary and then they move. Soon after COVID, he said that you could see how much it takes to keep the world locked down and still. So I think it's an awareness of the world – and I've mentioned the world rather than globe or the world map, because you can see that there's a world of relations being proposed rather than a global connectivity of geographies and places and resources. And it's operating at levels beyond the map.

How do you see the biennale's role within Saudi Arabia's rapidly developing cultural landscape?

NR: I mean, locally, it's the biggest platform for contemporary arts, which attracts the highest number of visitors for contemporary arts, being a publicly funded platform in a country that's still actively producing those spaces and infrastructures. And so this is where a large portion of the public comes to encounter what it means to visit a contemporary art space, essentially.

SA: I think Nora's absolutely right in mentioning the public, because I mean, a lot of the lingo around exhibitions has turned the public into audiences. Whereas the public is always a very generative and churning kind of space. Because who are the 'we' in the public? It's a contested question. It's not a resolved question, because new generations come, they have their priorities. Social norms change because of exposure. So doing a biennale in the region and in Saudi is also to participate in the dialogue of what is meaningful to the various publics that constitute this place.

The biennale emphasises collective imagination and resilience. What role can an event like this play in our current moment of global uncertainty?

NR: I think we're so bombarded with horrible news and images of a world that not everybody subscribes to. So I think it's really important for people to encounter different kinds of stories, different kinds of histories that we can learn from. And feel a sense of connection, feel maybe energised by stories of resilience and continuity, and see different representations of a world that can be otherwise.

SA: It is interesting that the very first and bold large-scale event for contemporary art in Saudi is a biennale. They could have started somewhere else. They could have started with art fairs or auction houses. So to have started with a biennale really made us also feel kind of emboldened. I mean, imagine what it does to the next generation of artists here. They're on their roadmap. It's works that they're reading and in conversation with in a biennale rather than in booths of an art fair. So that sets up a journey and a dialogue with the contemporary art field and with your peers around the world in a way that's completely different.

And we can see the impact, say, the Sharjah Biennale had in the UAE in the same way. I think it's one of the best biennales in the world. And really the way it positions histories from Africa or the Global South. I think it was foundational for a lot of our practices. I also think while there might be a lot of cynicism around biennales in the West, it sometimes may be misguided – it may be because they're losing control of the narrative, because the best biennales are happening in Asia. We are participating in that kind of infrastructure, where the biennale isn’t just an exhibition, but a discursive platform.

The Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2026 is now on until 2 May in the JAX District, Diriyah, Saudi Arabia.