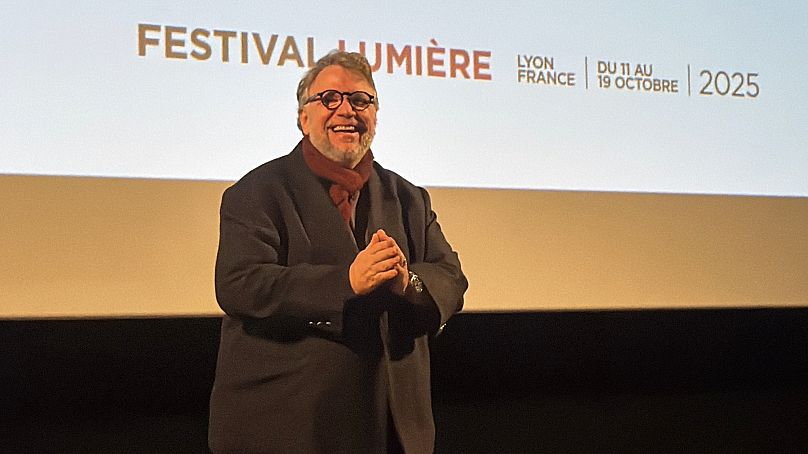

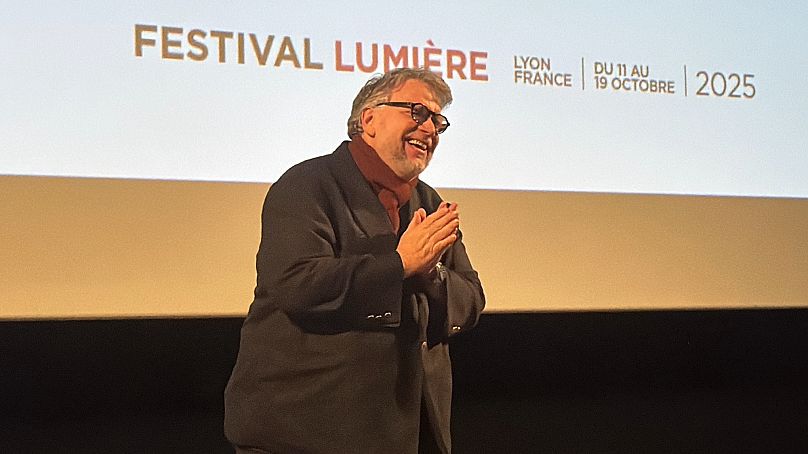

"Art is not only necessary, it is urgent. And AI can go f*ck itself!” Guillermo del Toro is a guest of honour at this year’s Lumière Film Festival. He presents his adaptation of Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein", which audiences got to see on the big screen before it streams on Netflix next month.

For Guillermo del Toro, the master of beautiful macabre and haunting cinematic fairytales, Frankenstein isn’t just his latest movie. It’s the culmination of a life’s work.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The Oscar-winning director of classics like The Devil’s Backbone, Pan’s Labyrinth, Hellboy and The Shape of Water, makes no secret of the fact that Mary Shelley’s creation has been a huge influence on his art since the beginning – from 1992’s Cronos to 2022’s Pinocchio.

More than that, it set him on a path to becoming a filmmaker.

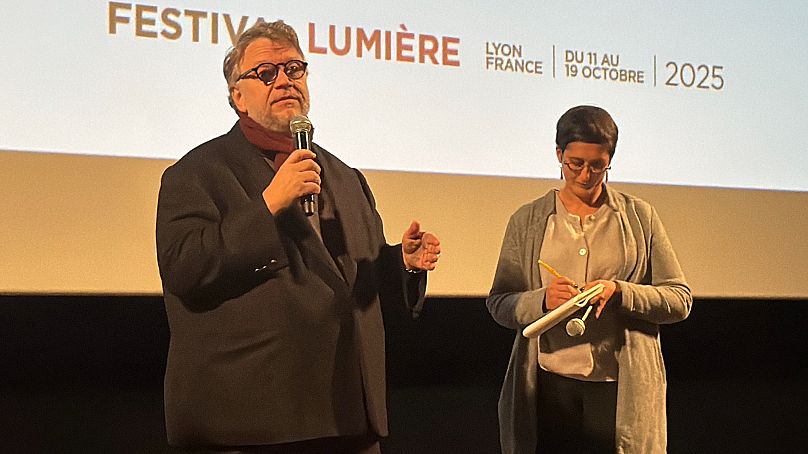

Speaking in front of a packed theatre in Lyon, for the 17th edition of the Lumière Film Festival and prior to the big screen screening of Frankenstein, the 61-year-old shared that he saw James Whale’s 1931 film, with Boris Karloff as Frankenstein’s monster, when he was just seven years old. More than that, he saw it after going to mass.

“When I saw Boris Karloff, I understood religion in that moment,” he said. “I understood Jesus, ecstasy, the immaculate conception, stigmata, the resurrection... I understood that I had found my messiah.”

He added, with a smile on his face: “My grandmother had Jesus. I had Boris Karloff.”

Del Toro continued: “Four years later, I read Mary Shelley’s book – the 1818 version, which is the less filtered, the most savage and the purest. My friends grew up dreaming of Farrah Fawcett – I dreamt of the Brontë sisters and Mary Shelley.”

“For me, I discovered that everything I couldn’t do as a ‘normal’ child in Mexico, it was all there in the romantic and gothic imagination, as well as in monsters.”

Indeed, Guillermo del Toro has been telling monster stories for as long as he’s been making movies, and Frankenstein is something of a “culmination”.

The filmmaker went on to share he was glad he had to wait so many years before getting to make his take on "Frankenstein"; because this story, which in del Toro’s mind deals with paternity - and when you watch the film, how sins can be transferred from generation to generation – required the passing of time.

“I’m happy that I'm older - and more tired - to tell this story because the child that saw Frankenstein when he was seven years old and read Mary Shelley’s novel when he was 11 is still in me... But now I feel like Johnny Cash when he sang ‘Hurt’ - and you can’t sing that song if the person singing hasn’t felt pain, time passing, and the weight of things lost.”

He added: “I’m also glad because I didn’t do it as the son of my father, but as the father of my daughters.”

Moreover, the novel asked an urgent question in 1818 that still remains urgent today: What is it to be human?

“The answer to me is: to ask for forgiveness and to be able to forgive.”

The director continued: “We live in dangerous times – times when we’re ashamed of our emotions, in which we’re told that art is not important and that we can make art on a f*cking App...”

This was met with applause from the public, who clearly understood the weight and importance of what he was saying at a time when AI prompts are insultingly labelled ‘art’.

“When they rob us of art and emotion, that leads us towards the aesthetics of fascism,” said del Toro. “In this film, all the sets are real, the decor is human-sized, there are painstakingly created miniatures... It’s an opera, made by humans for humans. It’s a film that’s there to remind us that art is not only necessary, it is urgent. And AI can go f*ck itself!”

His comment was met once again with thunderous applause, and as he wished the audience a pleasant viewing experience, the Mexican maestro left the stage with an impassioned: “Viva Mexico, Cabrones!”

Viva Mexico. Viva Shelley. Viva del Toro.

Frankenstein hits select theatres tomorrow and streams on Netflix on 7 November. Itis this week’s Film of the Week. Stay tuned to Euronews Culture for our full review tomorrow.