Euronews takes a look at Ukraine's most vital wartime writers and the onset of 'veteran' literature.

March 9 is very special for Ukrainians. It is the birthday of our prophet-poet Taras Shevchenko (1814-61).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

You can find his monuments in all Ukrainian cities; every Ukrainian pupil has to memorise his poems in literature classes; his ideas of the Ukrainian nation lie at the very centre of our identity.

He was prosecuted for his views by the Russian Empire, but his poems helped to shape a modern independent Ukraine.

Symbolically, right after the bloody end of the 2014 Revolution in Kyiv, Ukrainians commemorated his 200th birthday while Russia started the annexation of Crimea.

The period from the end of February 2014 till 24 February 2022 was ambiguous. The machinery of Russian propaganda presented it as an internal Ukrainian conflict or even a civil war. But Ukrainians commonly see this as an initial phase of the Russian-Ukrainian war in which the nations are now embroiled.

Ukrainian writers responded to the events in different ways. Some joined the army, some provided the army with ammunition, food and equipment, some visited the frontline and entertained the soldiers, some concentrated on the literature, some combined all these activities.

Only a few Ukrainian writers decided to support the Russian side. For example, part of the literary circle “Stan” from Luhansk evacuated to the territories under Kyiv's control, and the poets Elena Zaslavskaya and Aleksandr Sihida left in Luhansk and became the poets of the “republic”. It is hard to tell what were the main motives – vulnerability to the propaganda or ambition to become top poets of “new republic” perhaps.

Writers from the occupied territories (who escaped the occupation or moved from there previously) felt the war the most acutely.

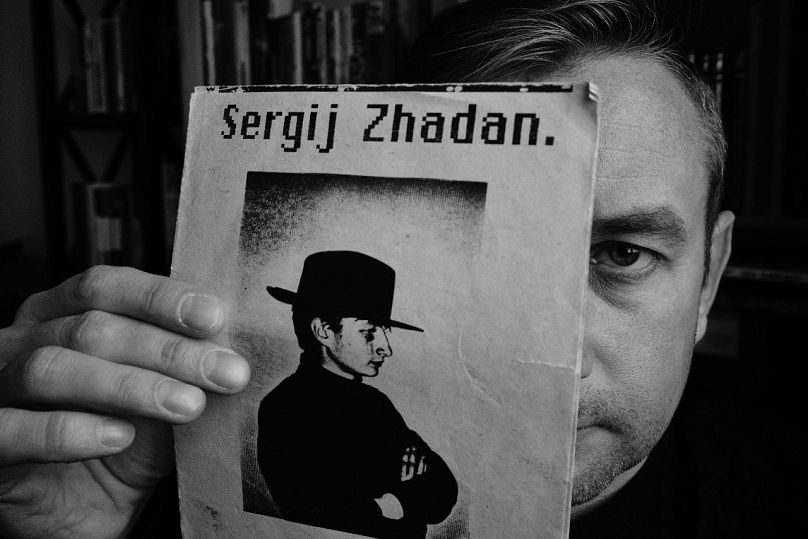

Serhiy Zhadan (born in Luhansk oblast) is one of the most popular and influential Ukrainian authors. He writes poetry, prose and drama. In all three genres, you can find texts connected with the war. The novel “The Orphanage” (2017) presents the mentality of the Donbas people.

The metaphor of the orphanage is very powerful. On the one hand, victims of the war are presented as those who have no parents, i.e. the state is not able to protect them. On the other hand, they have some problems with their identity, they are vulnerable to the propaganda, they are not sure which side of the conflict is better, they just wait until it ends, but at the same time the frontline gets closer and they have to do something.

Lyubov Yakymchuk (born in Luhansk oblast) published a powerful collection of poems entitled “Apricots of Donbas” (2015).

This is an excerpt from the English translation of the poem “how I killed”:

Volodymyr Rafeenko is a Donetsk writer who was tightly connected with Russian literature before the war. He wrote in Russian, his books were popular in Russia, he was awarded prestigious Russian literary accolades. But after 2014 he mowed to Kyiv, joined the Ukrainian writing community and even switched to Ukrainian.

He wrote an autobiographical book about it called “Mondegrin”.

“During all my life I was speaking, writing and reading in Russian - I needed no protection. But when I was thinking about the armed bastards who occupied my city to save me from my country and from the language of my grandmother`s fairytales, my head began to rattle so loudly that there was no life,” he wrote in a column for Deutsche Welle.

Stanislav Aseev (from Donetsk) experienced the most dramatic fate.

He worked as a secret reporter under Russian occupation in Donetsk until 2017 (publishing his reports under the nickname Stanislav Vasin). But eventually, Russians caught him and imprisoned him in the “Izolatsiya” prison which is known for immense tortures. He was sentenced to 15 years for espionage during a trial which was defined by Amnesty International Ukraine's Director as “the latest affront to human rights”.

At the end of 2019, Ukraine finally exchanged him and other prisoners for Russians. Aseev wrote 'The Torture Camp on Paradise Street', a philosophical account of his imprisonment. It is not only a diary but a profound analysis of other prisoners, the prison's administration, the nature of the tortures dealt out and possible reactions and traumas.

His book is often perceived as a dialogue with Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl. According to Ukrainian writer and critic Svitlana Pyrkalo, “both authors question the meaning and value of life."

"Frankl, who studied suicide and depression professionally before the concentration camp experience, says that even during the greatest suffering, a person has the freedom to choose what to think and what to hope for. Even in a concentration camp, a person can choose life, and this will help to avoid death. For Aseev, his freedom is the opportunity to choose death, and this is what gives him a chance for life.”

From 2014 till the beginning of 2022 more than 400,000 people took part in the war. As a result, a new type of Ukrainian writer appeared – war veterans without previous literary activity.

Veteran literature is predominantly non-fiction. People write about their personal experiences. Detailed descriptions of destruction, death and suffering, heroic deeds, self-sacrifices and cynical reactions. But for some writers veteran experience was just a starting point for their literary career.

Serhiy Leshchenko (Saigon) wrote a brutally realistic veteran text, “Dirt [*Khaki]”, describing his own war experience. Afterwards, he wrote a book about life in his village “Yupak” and won one of the most prestigious awards in Ukraine, the “BBC News Ukraine Book of the Year”.

Following this, together with fellow veteran Martin Brest, he wrote the war novel “Mozambique” – with a well-constructed plot and two narrators. The setting was the same – war in Ukraine, but this time it was fiction.

Among Ukrainian writers and critics there was a discussion about the quality and nature of good literature. Some professional writers decried veterans for not having enough literary skills, while some veterans blamed professional writers for being artificial and lacking real-life experience.

On February 24, 2022, this minor discussion suddenly stopped being legitimate. Now every Ukrainian is a veteran fighting in his or her own way, gaining real war experience.

This 19th-century Romanticist rhetoric of Taras Shevchenko is oddly apposite for the situation of Ukrainians today.

It may be that the immense range of war experiences will be later reflected and sublimated in Ukrainian literature, and stand as a golden age.