All alcohol and tobacco products in Turkey became up to 30 per cent more expensive overnight on January 1. How is this drastic increase is discouraging people from dining and drinking out?

At the start of 2022, the rate of inflation in Turkey hit an eye-watering 36 per cent.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The drastically rising cost of living marks an unwelcome landmark in the country’s third economic crisis since the beginning of the millennium.

Deep and unflinching marks are being left in some of the country’s most valuable cultural institutions.

A new tax on the sale of tobacco and alcohol is only adding salt to these wounds – primarily for club-goers, restaurateurs, and the country's 'Tekel' shops.

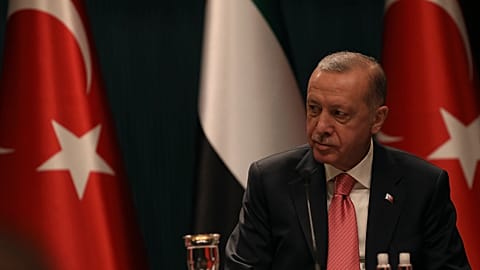

Euronews spoke to some of the people worst affected by President Erdoğan’s “new economic programme” to understand how going out in the country is fast becoming a luxury.

What is the new tax and how does it affect Turkey's nightlife?

From January 1, the 'Special Consumption Tax' placed on alcoholic drinks and tobacco products rose by 47 per cent.

Beers, wines, and cigarettes became up to 30 per cent more expensive overnight – hard to swallow news for an industry already ravaged by COVID-19.

The increase is central to a package of other rising costs, such as public transport and gas, created as part of Turkey's uphill battle with its economic crisis.

“Our sales have dropped sharply,” says Hakan Onay, manager of Istanbul’s Eleni Restaurant.

“People can not go out and have a meal with their friends without thinking [about] the prices. So we had to start very different services.”

Eleni Restaurant is in fact a ‘meyhane’ in Besiktas, a historic commercial hub 6km northeast of the Turkish capital’s own city center.

A ‘meyhane’ is a place that sells alcoholic drinks with small dishes (mezes). These eateries are traditionally tied to long nights of eating, conversation, and drinking the famous Turkish traditional alcoholic spirit ‘raki’.

After the tax hikes on alcohol, Onay has had to raise Eleni’s menu prices by 20 per cent.

In recent years, the restaurant begrudgingly adapted to a bring-your-own-alcohol policy with the hopes that diners discouraged by the price of alcohol would still come for the food.

“It sounds weird. But yes, we let our customers bring their own raki. Because we sell a 700ml classic bottle for between 500-600 Turkish lira (€31-38). The cheapest raki in Tekel shops costs 279 lira (€17) after the new tax addition. So they come to our restaurant and pay just for the food and mezes.”

The country’s current situation has pivoted businesses from aiming to make a profit to trying to evade closure.

“On Sundays and Mondays, we have fewer customers compared to Fridays and Saturdays. So on these days we sell raki with the market price. We don’t put any profit on it. That’s the way we can keep them coming, and keep our business running.”

'Our customers cry out'

Business owners warn that the consequences of the tax hike are rippling through Istanbul's famous nightlife.

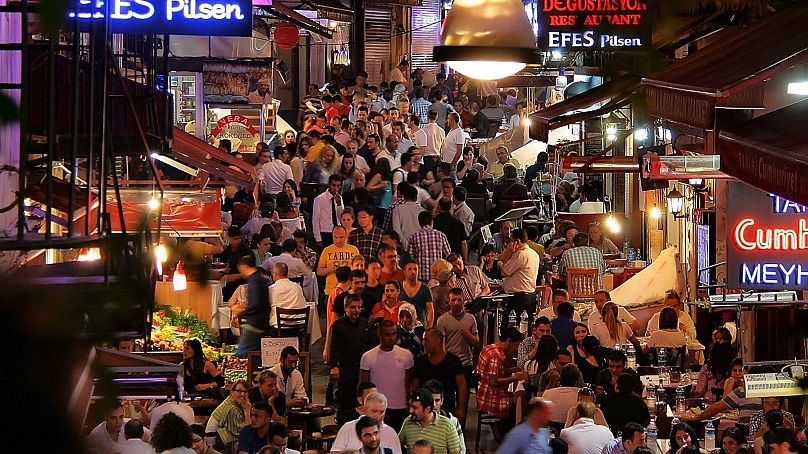

The capital's Istiklal Street is usually crammed 24/7 with partygoers and tourists – on a good weekend, over 3 million people pass through its 1.4 km avenue of bars and clubs.

Cem Balat, a bar owner in Istiklal Street’s Beyoglu neighborhood, says the drop in customers and profits is hard to ignore.

He explains that eating and drinking outside of people’s homes has become a luxury, especially for the country’s young people.

Meanwhile, regular alcohol suppliers are now discounting bulk buying in order to retain income.

“We had to buy four times more alcoholic drinks from our supplier [...] before New Year's Eve. Cause there was a 30 per cent price hike, by doing this, we paid less.”

“Our customers cry out – recently, I had a strange conversation with a customer. He said: “When I was a student 10 years ago, I could go out and drink more than today. Now I have a job, making money but I can hardly afford going out with friends. It’s all about the economy and purchasing power. I consumed more alcohol when I was a student.”

The customer might have had a point – while the government hiked the monthly minimum wage by 50 per cent to 4,250 lira (€270) for 2022, the cost of living demands that money is spent far away from leisure.

Balat isn’t optimistic about the future of Turkey’s policies to combat their crisis.

“We are going to face harder times in 2-3 months. The dollar and euro still go up against Turkish lira. I have a fear [I will lose] my job.”

Cinemas also feeling the pinch

“In the last 2-3 years movie tickets have already risen so much,” says one chain cinema manager who spoke to Euronews anonymously.

“In recent months the dollar and euro rose so hard against the Turkish Lira. And the inflation rate is so high now like I've never seen before in my life. This affected our business. People started to cut the budget that they spend for their social life, on cultural activities.”

He added that Turkish people had no choice but to economise their life.

“There is no certain price in the shops. Every day there is an addition. So people prefer to stay at home: they cook their own food, families watch TV, Netflix, Exxen, or other platforms. Or some internet content. Because it’s almost free.”

Young people and students feel more limited than ever

Even outside the capital’s streets, students and teens are feeling the limits in how they choose to spend their downtime.

Tuba Celik, a nursing student who lives in Tekirdag, near the Greek border, says that she and her classmates can go out just for drinking tea or coffee – ”maybe fast food”, if they’re feeling indulgent, but certainly not every weekend.

It’s a stark contrast to her days in high school four years ago, where she and her friends went out every weekend with very little money and were still able to have a good time

“Last week, I wanted to buy a coat. It was more than 1000 TL (€63), I couldn’t believe it. Just a regular coat. And I couldn’t buy it. Obviously, our purchase strength dropped 2-3 times compared to 5 years ago.

"The worst thing is, for instance, my little sister... She is in secondary school. And she thinks about the economy at that age. She follows [the strength of] dollar and euro currency. It’s a pity for the younger generations.”

Is 2022 the year Turkey's nightlife dies?

Liquor and tobacco stores – known as Tekel shops, after the state-ran business that once supplied the country with its vice – are disappearing rapidly as Turkey fights with the consequences of its policies.

Tekel Shops Federation President Erol Dundar tells Euronews that President Erodgan “just killed the social life of Turkish people.”

“He doesn’t drink alcohol but he doesn’t respect who drinks it. The nightlife and alcohol culture is dead. He wants to punish the people with high taxes who drink and smoke. Now people are looking for smuggled alcoholic and tobacco products – ‘cause it’s cheap.”

75 people across the country are said to have died through the purchase of cheaper “bootleg” alcohol.

Dundar believes the government is full of “incapable politicians” that are “full of debt” and unable to run the state. He, like many others, believes there is a lack of transparency about just how dire these circumstances are for people like him.

The TUIK (Turkey’s Statistics Institution) may say the country’s rate of inflation is 36 per cent – a shocking figure in itself. But Dundar believes the figure exceeds 100 per cent.

“That’s the number the public sees in the supermarkets and shops’ shelves.”

A more reflective statistic of the state Turkey finds itself in can be found in those outlining Tekel Shops’ futures, he argues.

“Ten years ago there were 95,000 Tekel shops in Turkey. Now, there are only 49,000. 50 per cent went bankrupt – half of them gone!”

According to Dundar, the livelihoods of 3 million people are tied to making their living with business in Tekel shops: the producers, farmers, workers, shop owners and sellers.

For now, at least. In his eyes, only the government is to blame for placing such a chokehold on culture and leisure in the country.

“Honestly, they (Erdogan government) don’t have nightlife, they don’t have fun. And also they don’t want the others to have fun.

“That’s the brief of our society’s life in Turkey recently.”